Tonight is the first night of Passover, the Jewish holiday when families and friends gather to read and discuss the events of Exodus. For many Jews, Muslims, and Christians, the Book of Exodus records literal truth, an account of events exactly as they happened. Most modern historians, though, agree that the exodus story did not occur exactly as described in the Bible. There are several events which are thought to have occurred between the fourteenth and twelfth centuries BCE that make up the basis for the Exodus story. One particular source of evidence that is particularly interesting to those of us at Tatter is the techniques and terminology surrounding the production of linen garments.

In ‘Women’s Work: The First 20,000 Years,’textile historian Elizabeth Wayland Barber, describes the unique method by which ancient Egyptian spinners and weavers kept linen thread from breaking while they wove lengths of precious cloth. Because flax is a thirsty fiber, Egyptian spinners found that it was easiest to work with pliable wet thread.

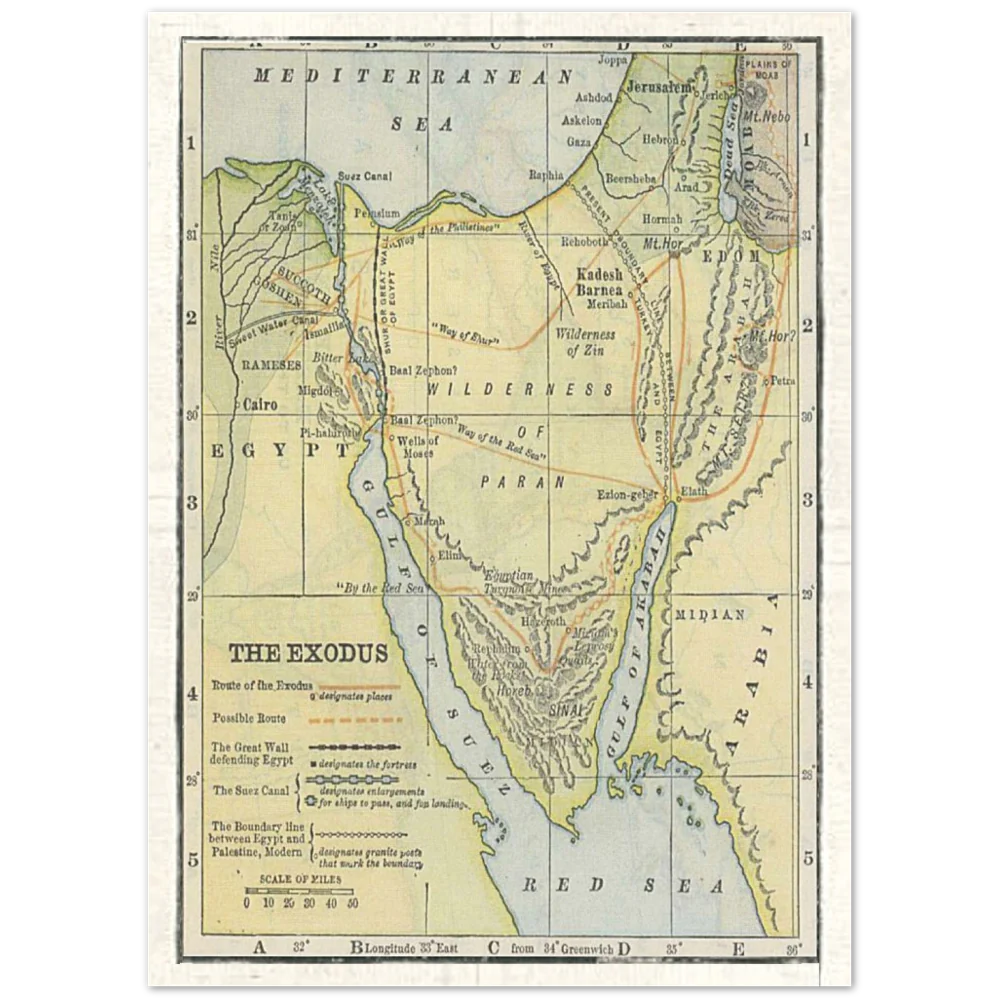

The crude yarn was kept in a bowl of water with loops on the bottom to prevent the fiber from jumping out. The spinner would then be free to smoothly pull the flax from the bowl and feed it into the spindle without having to pause her work. Such bowls had only been found in Egypt until the fourteenth century BCE when they began to show up in the regions which would become Judea. These, along with Egyptian-style clay loom weights, suggest a group of weavers from Egypt migrated with their families from Egypt to the Levant around that time.

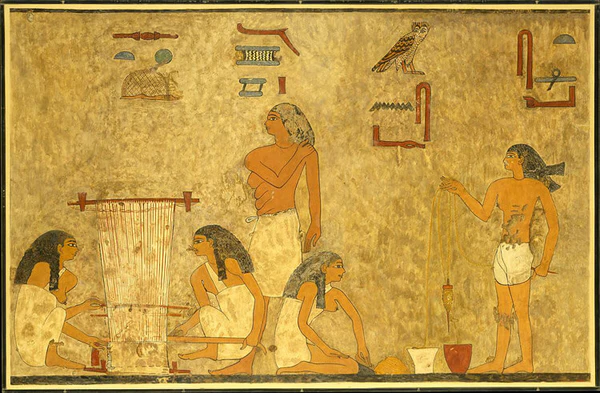

Linen production in ancient Egypt was primarily the work of enslaved people, both men and women. Linen was not only essential for daily life in Egypt, but also a key source of revenue which required difficult and skilled labor. Flax was cultivated, harvested, bundled, and either dried or rhetted by men and then cleaned, spun, and woven by women and children. Paintings from excavated tombs and preserved on crumbling papyrus show laborers under the watchful eye of an Egyptian overseer in large weaving rooms. Because the only record of the wretched conditions in the weaving rooms comes from times in which Egyptian citizens were put to work, the conditions for the enslaved were undoubtedly worse. These weaving rooms were generally on large estates owned by temples, where priests were expected to keep large stores of completed textiles. The work of the enslaved Israelites and of other nations in bondage would have been grueling and seemingly endless.

Those weavers and their descendants who managed to escape Egypt and travel across the Levant, upon arriving in their new home, were able to at last turn their skill to their own purposes. The first thing that they are recorded weaving of their own free will are textiles to create a tabernacle: a place to worship.

Upon building the Tabernacle, Moses calls upon the women to furnish it with spun wool and linen cloth. Once again, we can find evidence of Egyptian spinning traditions in the words used to describe the creation of textiles. Two verbs are used here for spinning: tavah (טָוָה) for spun wool and shazar (שָׁזַר) for ‘twisted’ linen. ‘Shazar’ is a loanword to Aramaic, almost certainly Egyptian in origin (given its similarity to ‘sht’ and ‘s-sh-n’, the consonants used to designate the act of spinning and the making of woven fabric on ancient tomb wall paintings). The Egyptian word ‘sht’ also may lend itself to the prohibition in Leviticus and Deuteronomy against wearing ‘sha’atnez’ (שעטנז) meaningmixed fabrics (sometimes specified as mixed linen and wool). ‘Sht’ meaning woven fabric and ‘n’dz’ meaning ‘false’ or ‘adulterated.’

Religious scholars and ancient historians of the Levant or Egypt have their own way to map out ancient history. After all, even the Book of Exodus– written circa 950 BCE– was based on an oral history which had been passed down for at least three hundred years before being put to parchment. Every Passover seder I have attended reads the Haggadah (a book which lays out the order of the celebration) differently, and each family finds a different message inside the story than the one they had found the year before. At Tatter, we map history in textiles: the warp and the weft of civilizations as they intersect and diverge, as they break and are mended and break again. We do so because textiles are central to the human story. They keep us warm, protect us from the sun, allow us to gather food, create shelter, even take to the seas and traverse the world. We also map history in textiles because they are so often ignored as the work of marginalized, impoverished, and enslaved populations.

By mapping the Exodus in linen, we can see in greater detail what bondage in Egypt would have looked like for the Israelites. We can also see their hope for what life would look like in the promised land. As the Israelite women baked their bread with no time to let it rise, we know that they not only grabbed their timbrels but also their spindles. They knew that they would need to eat in the immediate aftermath of their escape, but they also hoped that they would survive long enough to make textiles, to clothe their children and their children’s children, to craft a tabernacle where they would have a place to worship. They fled Egypt with their tools and passed on their knowledge so that their descendents in Judea would know to shape wetting bowls for flax and bake clay into weights for looms. They fled Egypt because they hoped they would survive to create a future where the work of their hands would be theirs: a time of peace, a time of freedom.

READ MORE AT TATTER

Women’s Work – the First 20, 000 Years: Women, Cloth, and Society in Early Times by Elizabeth Wayland Barber, call number GN799.T43.B37

REFERENCES

Exodus, Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., www.britannica.com/event/Exodus-Old-Testament.

Moore, Megan Bishop, and Brad E. Kelle. ‘The Disappearance of the Egyptian Sojourn, Exodus, and Wilderness Wanderings from Critical Histories of Israel’ Biblical History and Israel’s Past: The Changing Study of the Bible and History. Eerdmans, 2011.

Philologos. “The Proof of the Exodus Hidden in the Ancient Word Sha’atnez ” Mosaic.” Mosaic: Advancing Jewish Thought, 7 Sept. 2022, mosaicmagazine.com/observation/religion-holidays/2022/09/the-proof-of-the-exodus-hidden-in-the-ancient-word-shaatnez/.

Wayland Barber, Elizabeth. Women’s Work – the First 20, 000 Years: Women, Cloth, and Society in Early Times. W.W. Norton, 1996.