From fabric books, to dolls, to abstract forms, “soft sculpture” has an unknowably long history, and can be a very particular kind of portraiture or tool for storytelling. Rag dolls can be traced back to ancient civilizations, as can baskets and other woven forms. Though the term ‘soft sculpture’ is quite contemporary in the art world, the practice has accompanied us throughout human history.

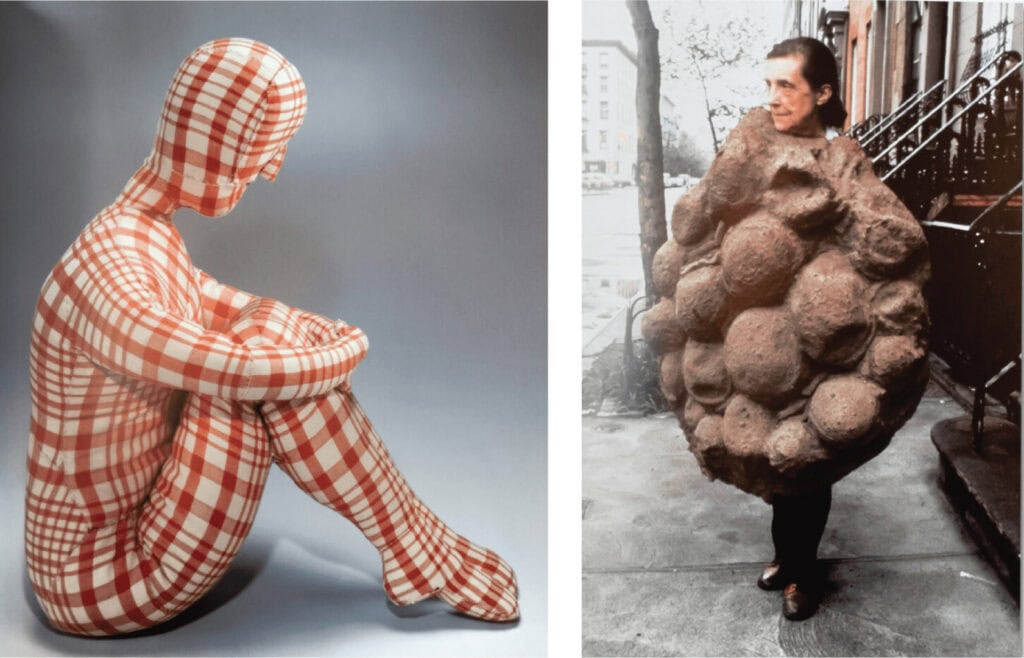

The “soft sculpture movement” of the 1960s expressed a significant departure from traditionally rigid sculptural forms, embracing pliable and tactile materials like fabric, foam, and stuffing. Prior to the 60s the power of ‘sculpture’ was associated with the permanence of solid and fixed materials. Pioneered by artists such as Claes Oldenburg, Yayoi Kusama, and Louise Bourgeois, the soft sculpture movement challenged the conventional norms of sculpture by introducing softness and flexibility – qualities better suited to certain conceptual ideas. Soft sculptures blurred the lines between art, craft, and everyday objects, making the medium more accessible and relatable. Soft sculpture lent itself brilliantly to domestic themes. And as with all artforms employing textiles, cloth and other soft materials allowed for a more personal, tactile connection with art, often evoking warmth, intimacy, the biomorphic and the psychological. This shift helped redefine sculpture’s role in contemporary art, turning it from static and monumental to playful, humorous, and interactive.

The power of soft sculpture lies in its relationship to the body. Three dimensional forms made of soft and pliable materials inherently speak to their power to move, and our power to affect their shape were we to touch them. Far from inert, a soft sculpture can cascade, protrude, billow, drape or flutter. Our experience of these objects, whether or not we actually touch them, is informed by our knowledge that just by the weight of our heads or bodies, or the strength of our hands, we could pinch, squeeze, dent or flatten what we see.

Right: Louise Bourgeois

For makers, learning to form soft sculptures opens a world of creative possibilities but also connects us to a history of makers who intentionally brought cloth and fiber from two to three-dimensional space – further empowering it to do the personal and identity work it is uniquely capable of. Soft sculpture is typically lighter, more mobile. It can be held, played with, passed between children and treasured into adulthood. Unlike their stone, clay, ivory, and metal counterparts, woven, stitched, and stuffed sculptures and vessels are most often made in women’s spaces by women and children. Their very softness and the ephemeral nature of their construction means that they rarely last longer than a few centuries at best. Anyone who has held the rags of a childhood toy knows how quickly something beloved can be worn to nothingness over the span of a single childhood.

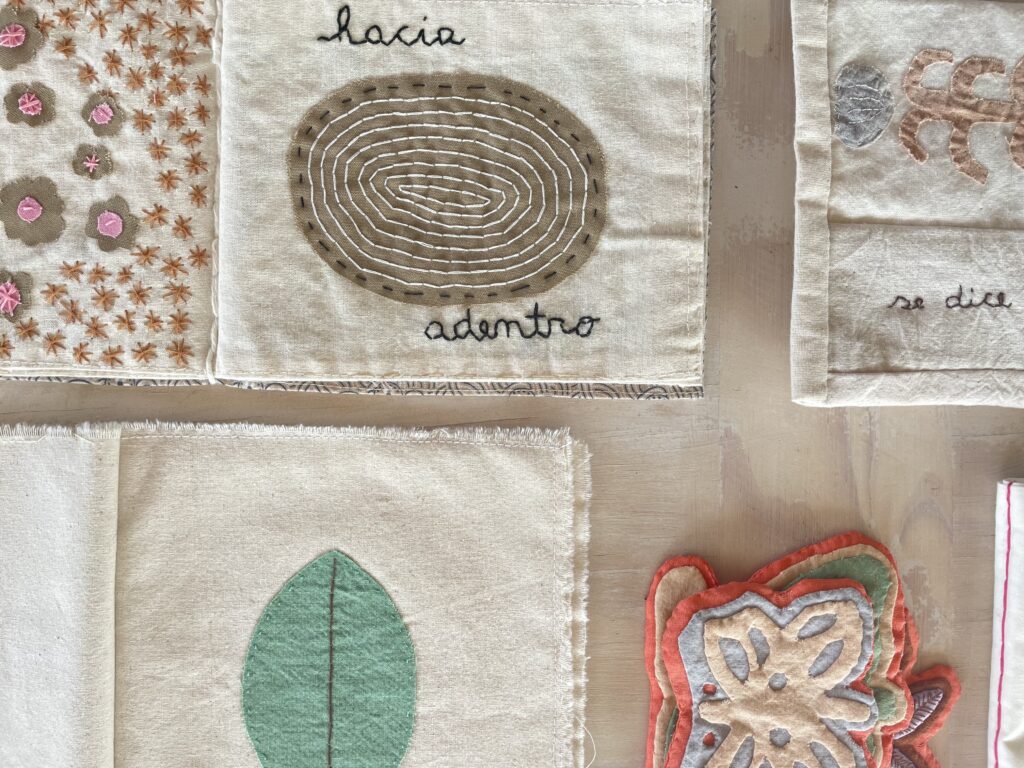

At TATTER we choose to contextualize our three-dimensional workshop offerings by speaking of them in this way: exploring the concept of ‘soft sculpture’ as it relates to sculpture more generally, but also to acknowledge that sculptural impulses are as old as humanity: the earliest indigenous makers who explored psyche by making figurines or ensured survival by ingeniously weaving helpful containers with materials at hand. By grounding these offerings in relation to these lineages as well as more contemporary thinking, it is our hope that we may access presence of mind in our personal art practices ultimately to see one another more clearly and truly enjoy the power of our work.

Soft Sculpture Workshops at TATTER

Featured image: Ironing Board, 1963, Yayoi Kusama