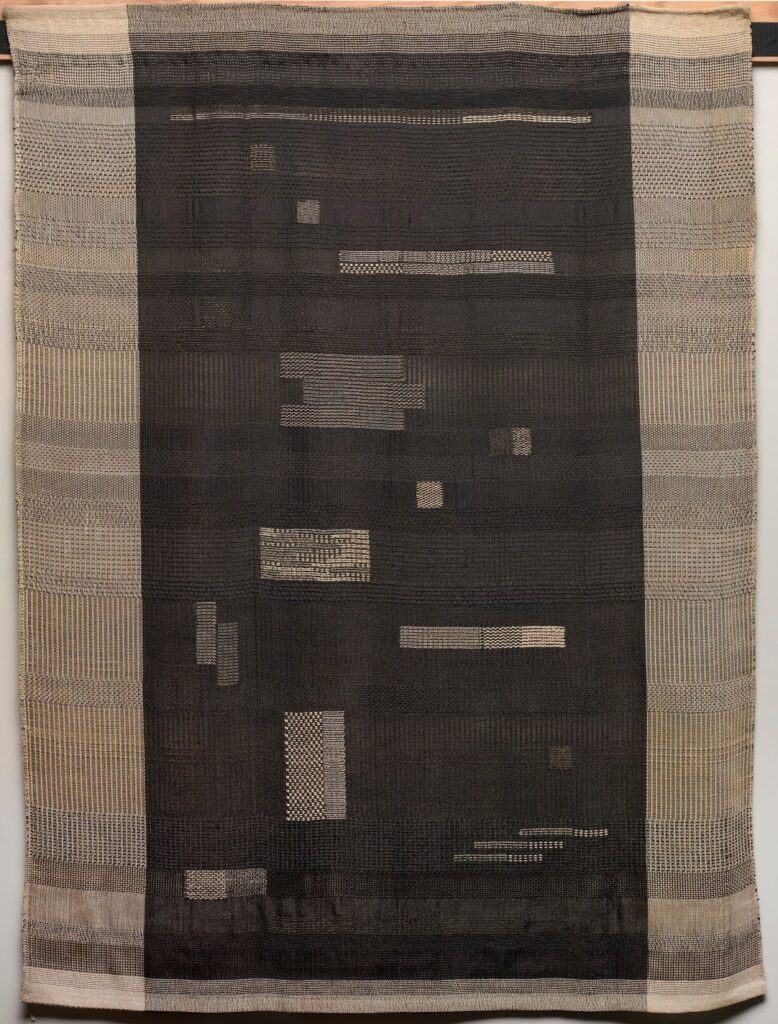

With its graphic array of patterns and textures in vivid thread colors, Gunta Stölzl’s (1897-1983) 1928 Slit Tapestry Red/Green explores the possibilities that lie within the warp and the weft. At the time of its creation, this piece was radical in the world of design, exemplifying a new, modernist definition of weaving pioneered by women of the Bauhaus School. These artists embraced an understanding of traditional methods of handiwork as a means to discover new ways of manipulating fibers on the loom. They looked towards weaving as an art form whose elements and processes are distinct from pictorial mediums.Stölzl began as a student at the Bauhaus School in 1919, the same year as its founding by Walter Gropius (1883-1969) in Weimar, Germany. Gropius set out to create a school that offered students various workshops which investigated individual crafts, beginning with their basic materials, processes, and elements. The design school strived for art-craft unity, operating under Gropius’ belief that “for a design to function correctly…one must first of all study its nature”.

The weaving workshop was one of the few craft workshops to thrive from the beginning of the school’s time until its closing in 1933 under the pressure of Nazi forces. However, in the initial years of the Bauhaus, weaving was treated as an inferior applied art. In Bauhaus Weaving Theory: From Feminine Craft to Mode of Design, author T’ai Smith writes that weaving’s “materials and practices were considered subordinate to the more fundamental practice of form and color theory… or the functionalist logic of architecture… as a manual practice, weaving was seen merely to borrow or apply the formal and functional theories that painting or architecture developed.”

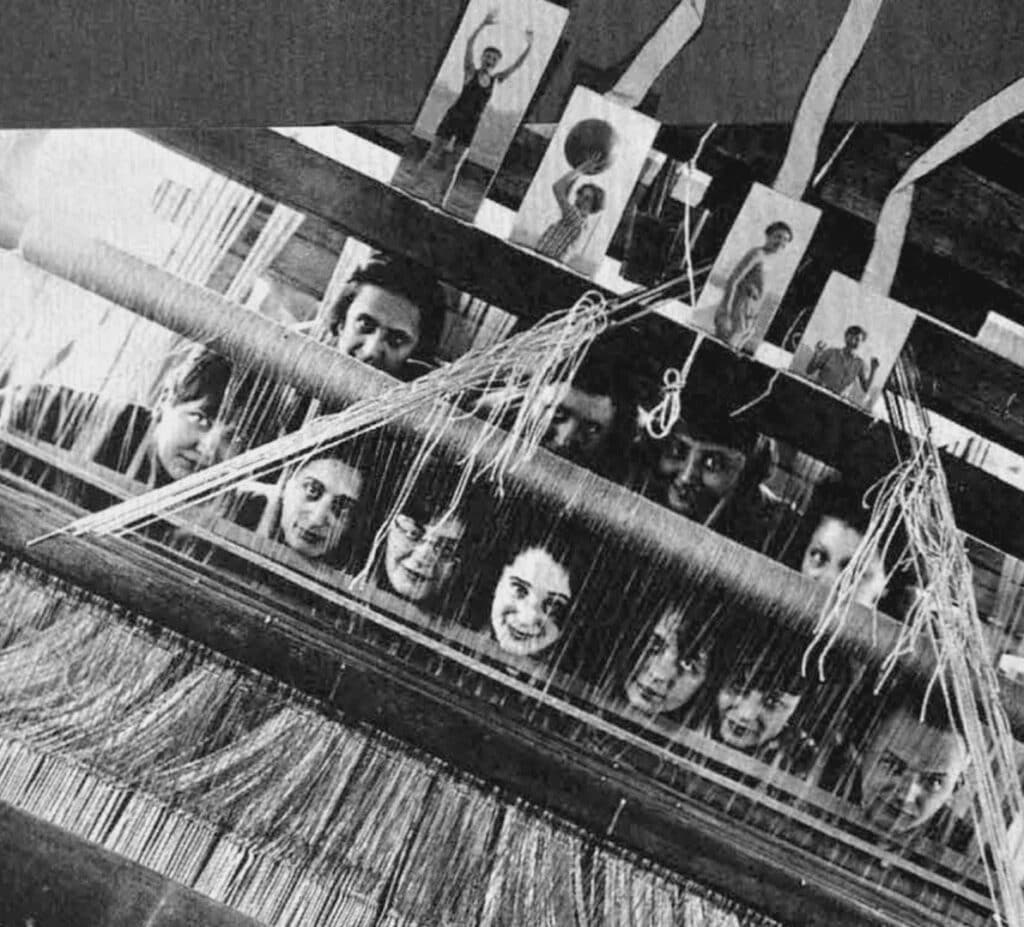

Gropius’s speech on the Bauhaus’ opening day made the strong assertion that the School would make “no distinction between the fair and the strong sex”, though this promise of inclusivity very quickly fell flat. During the first semester, 84 female students thrived, participating in a range of workshops while outnumbering the male student population of 79. This came as a surprise to Gropius, who, despite World War I leaving very young few men well and able enough to attend art school, seemed to have underestimated the number of women who would be interested in joining. Within a year of its opening, Gropius and the Masters Council quickly made it a goal to reduce the number of female students at the Bauhaus, and segregate them from “masculine workshops” more directly linked to architecture, such as metal working, carpentry, and furniture design. A Women’s Department was established, initially directing women into bookbinding, pottery, and weaving, however the Bookbinding Workshop quickly dissolved and the Pottery Workshop’s master discouraged women from joining. Students went to the Bauhaus School with expectations of self-directed learning, but this restructuring left weaving as the only viable area of focus for the female Bauhäusler.

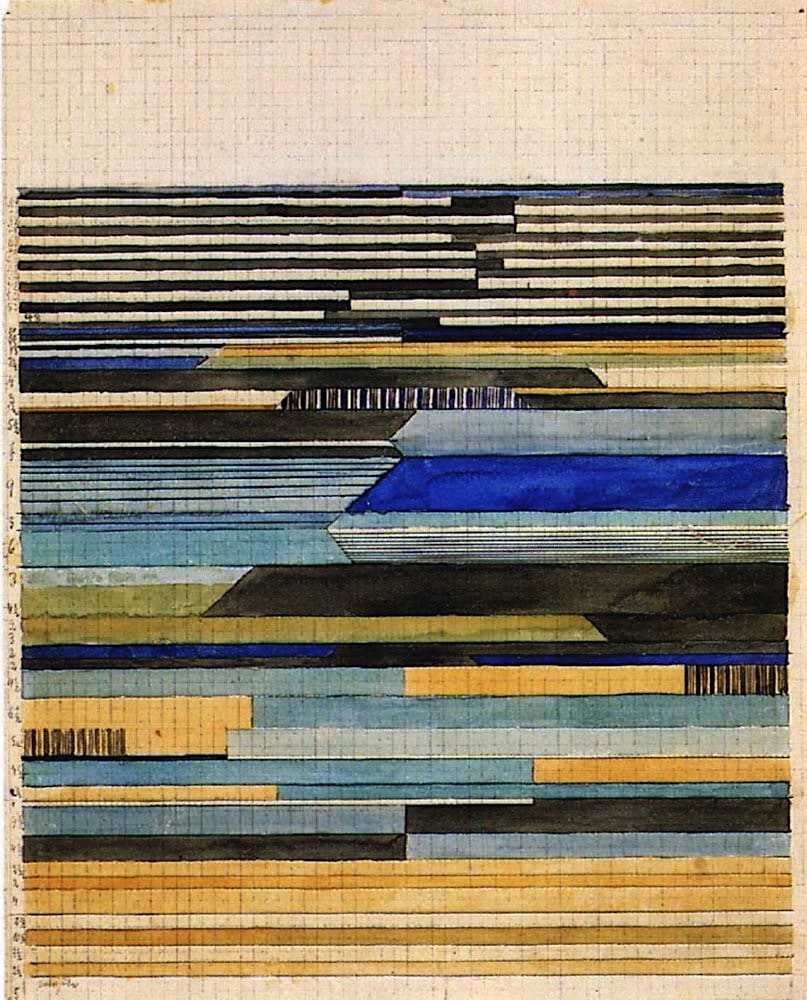

Smith reflects that the popular conceptions about weaving at the school were largely due to a lack of written theory on the craft, leading to its “feminized” status as dependent on more “masculine” mediums. Without outlined parameters and thought in regards to weaving, students’ work referenced theory developed for pictorial mediums like painting and drawing, instead of being guided by an understanding of the form and process of the weaving itself. Gunta Stölzl saw this reflected in many of the early works to come out of the weaving workshop, her own included, which she described as essentially “pictures made of wool” — translations of paintings or drawings in woven thread. These weavings were weak when compared to the “true” images they were referencing, situating the medium as limiting, with the loom and warp threads confining the maker to a structure that feels significantly more restrictive than an empty canvas if seeking to apply principles of pictorial mediums.

In order to establish weaving as a medium worthy of distinction, Bauhaus weavers like Stölzl, Otti Berger, and Anni Albers sought to develop the parameters of their craft through written theory, creating a modernist definition of weaving that reflected Bauhaus interests in functionalist design, while guiding students towards an understanding of their specialization and its principals. Their work developed alongside the idea that weaving should be determined by its function and means of production. Reflecting on changes in Bauhaus weaving approaches, Stölzl writes, “Today we do not weave flowers and fruit, figurative scenes and architectural perspectives, and neither do we devote ourselves to ornamental decoration. As said before, fabric design is concerned with designing surface structure that relates to surrounding things, adapts itself and fits in.”

Made up of interlaced fibers, the weave is defined by interconnectedness, and when understood as an individual medium with its own principals and distinct tactile traits, the possibilities which lie within weaving are revealed. The warp threads are proved to be not a more rigid canvas for the crafter to impose a design onto, but a unique matrix which is transformed on the loom with fibers, embedded within the work to create functional textiles with textures, patterns, and designs that are only possible through weaving. This distinction made by the Bauhaus weavers proved the intellectual nature of the craft. With this, the design of their modernist weaves became reliant upon the haptic and interconnected nature of its materiality and process– it is connected to the hands of its maker, its physical form, and the function which it serves to fulfill as the soft textile drapes and morphs to adapt to its environment.

REFERENCES

Gropius, Walter. “Bauhaus Dessau– Principals of Bauhaus Production.” 1926.

Stölzl, Gunta. “Weaving at the Bauhaus.” Offset, no. 7, 1926.

Otto, Elizabeth. “Bauhaus Femininities in Transformation.” Haunted Bauhaus, MIT Press, 2019

Weltge-Wortmann, Sigrid. Women’s Work: Textile Art from the Bauhaus. Chronicle Books, 1993.

Smith, T’ai Lin. “Bauhaus Weaving Theory: From Feminine Craft to Mode of Design”. University of Minnesota Press, 2014.

FURTHER READING AT TATTER

Women’s Work: Textile Art from the Bauhaus Sigrid Wortmann Weltge 1993 Call #: NK8850.W46

Bauhaus Weaving Theory: from Feminine Craft to Mode of Design T’ai Smith 2014 Call #: TT847.5.G4.S65

Design and For: The Basic Course at the Bauhaus and Later Johannes Itten 1975 Call #: N332.B38

Anni Albers and Ancient American Textiles: from Bauhaus to Black Mountain Virginia Gardner Troy 2002 Call #: N9500.A43.T76