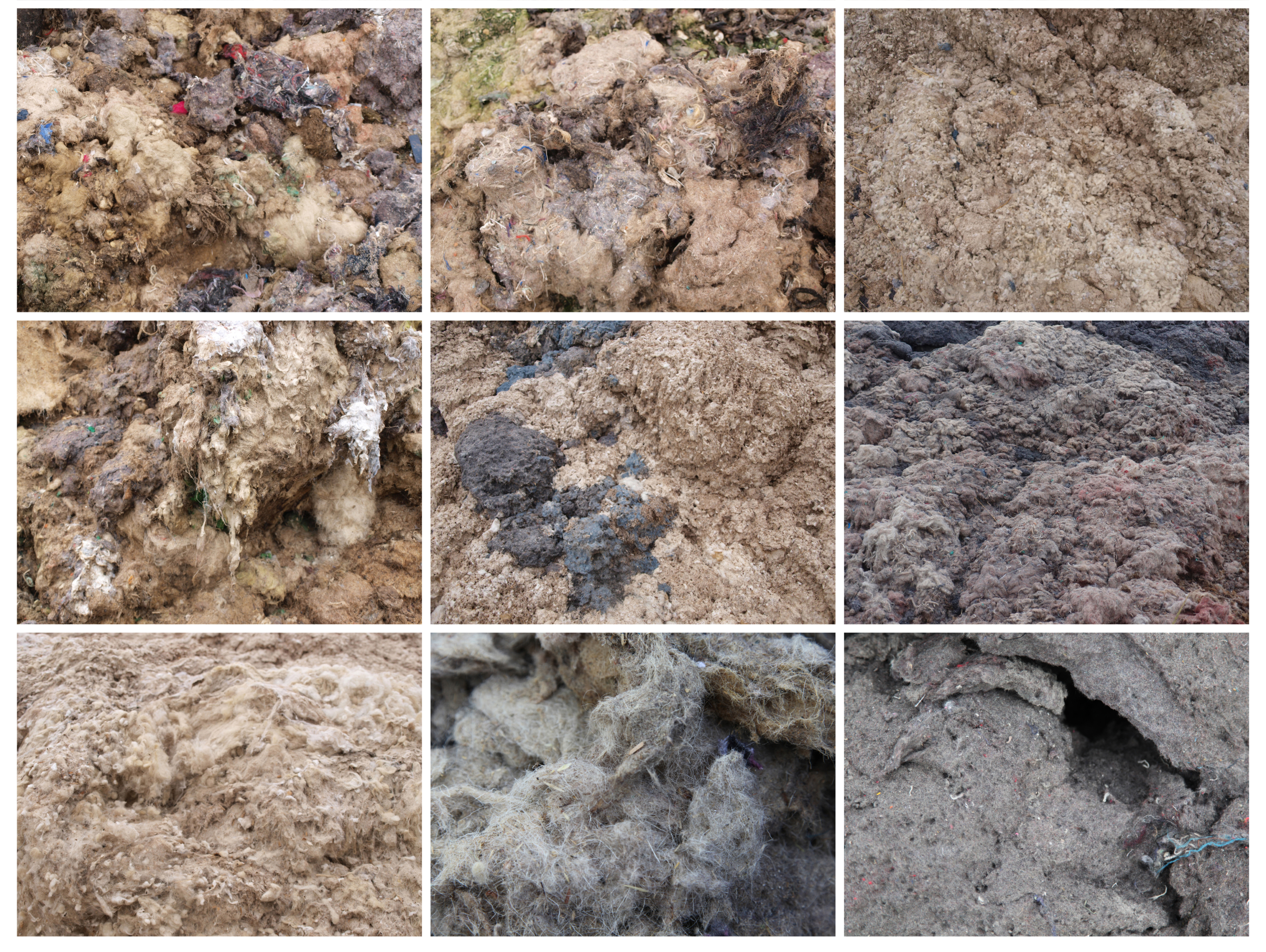

THIS SERIES OF PHOTOGRAPHS SHOWS A TYPOLOGY OF THE SHREDDED REMAINS OF USED WOOL, COTTON AND SYNTHETIC FIBERS: RAGS, SOCKS, CLOTHES, AND REMNANTS FROM THE TEXTILE INDUSTRY. MUCH, THOUGH NOT ALL, IS SLOWLY DISINTEGRATING INTO THE EARTH.

If you had been with me, you too might have seen the heap from the highway. It was tall enough to notice from the M62, the motorway that crosses England’s old industrial region and connects England’s two great port cities, Liverpool and Hull. It was hard to tell what it was, though. Most travelers probably pass right by. I had been told about the “shoddy heap” by a local amateur botanist who I’d met while working on my book about the poetry, power, history and potentiality of textile waste: Shoddy: From Devil’s Dust to the Renaissance of Rags.

Reaching about 20 feet at its highest point, the heap could easily be mistaken for an unusual geological formation. From a different angle, and closer up, it might appear to be a mound of animal manure (indeed it is located in an agricultural context, smack in the middle of a rhubarb farm), but for the fact that it’s dappled gray. The smell is notable: like rotten wool or perhaps a wet dog. Up close, small items glitter amid the gray—stray rhinestones, buttons, the occasional zipper.…. Look closer still. A whole world of possibility reveals itself: forms of textile and terrestrial decay and recomposition.

This series of photographs shows a typology of the shredded remains of used wool, cotton and synthetic fibers: rags, socks, clothes, and remnants from the textile industry. Much, though not all, of it is slowly disintegrating into the earth. In various states of chemical decomposition and sometimes arranged in strata-like layers, this debris has a potential biological purpose. Wool contains a high amount of nitrogen, which releases slowly as the fibers break down.

Going back hundreds of years, people have dumped textiles too old and ragged to be resold, repaired or otherwise repurposed, onto their gardens and fields. This was an especially prevalent practice before the Industrial Revolution, when clothes tended to be produced and discarded locally. Mechanical looms, spinning mules, and sewing machines would make clothing easier to produce and more affordable to populations, and as new clothes became common instead of rare, and worn clothes were discarded or exchanged at an ever- quicker pace. The working and middle class purchased and discarded more, while at the same time, more waste material, or “clippings,” were generated by the production process. With industrialization in the nineteenth century, wool scourers and rag sorters continued to send out their lowest end bits of wool, selling it to farmers. In Britain, it was said that to be especially helpful in cherry orchards and in the raising of hops.

I AM OBSESSED WITH TEXTILE WASTE. AS A FILMMAKER, ARTIST AND AUTHOR, I HAVE FOLLOWED IT FOR DECADES…MIDWAY THROUGH MAKING A FILM, MY PASSION HEATED UP, IGNITED BY THE NOTION OF CLOTHING AS SUBSTRATE RATHER THAN OBJECT.

I am obsessed with textile waste. As a filmmaker, artist and author, I have followed it for decades. At first, it was secondhand clothing (discarded garments): their use, reuse, and re-sale at markets world-wide, and their role in crafting and mediating human relationships. But midway through making a film, my passion heated up, ignited by the notion of clothing as substrate rather than object. I learned that some countries refuse to receive secondhand clothing if it has not been sufficiently “damaged”, in order to prevent its immediate resale as wearable garments. At that particular time, India had banned the importation of all but “mutilated” secondhand clothes. At an antiquated factory in Brooklyn, I saw machines tearing secondhand clothing apart to create a textile entity which could then be legally sold to such countries. The process of slicing old textiles immediately fascinated me, especially when I heard that the thrashing machine was named “the mutilator.”

After “the Mutilator,” I met “the Devil.” As I would learn, there have long been countless ways to reprocess textiles not worth reselling. Old wool clothing, and especially old cashmere, continues to have a high value as a material to be shredded (by “the Devil”) into an old-new yarn. “Shoddy” is the name given both to this process and to the product of manufacture. This happens on an industrial scale at cashmere factories around the world. Cotton fibers have always been much harder to rework than wool ones. Once it is shredded it is hard to respin. Old cotton is most valuable transformed into rags or shredded for stuffing, like the shredded denim used as home insulation.

Synthetic fibers are a waste management challenge and complex regeneration charge. Clothes made from synthetic fibers pose an even greater de-engineering problem than cottons. Despite the moves by companies like H & M to visibly demonstrate the ability to un-spin and re-spin their clothing, economics do not favor this strategy as anything more than a public relations ploy. While plastic bottle waste can be transformed successfully into fleece, synthetic textiles still pose remarkable issues. Instead, synthetics, like most cottons and poly blends, are turned into materials to be used for mattress padding, envelope stuffing, carpet lining, and moving blankets.

When all recycling possibilities have been exhausted, synthetics end up in heaps such as this one, along with as much wool waste as is let go by the new wool scourers. It becomes part of the complex aesthetic tapestry and ecology I explore. While some of this material is clearly wool waste, much or the heap looks like laundry lint. These striated mounds are baled-up dust collected from extractor fans in modern rag- grinding mills or collected in “cyclones,” the machines used to shake rags before shredding. The powdery excess of this process— modern-day “devil’s dust”— is compressed into bales, shrink-wrapped, and tied with wire. Once delivered to the field, the wires are clipped and the shrink-wrap cut. Some dust blows away across the fields, but moisture from the environment, and sometimes added water from a hose, help the bales retain their form. Then there are the sequins, zippers, boa feathers, and the shredded bits of other items that dot the countryside. I’ve even found the occasional brass button remains of army uniforms worn in battles long ago won or lost.