In many ways, macramé feels like a quintessential 70s craft: think thick cords knotted into plant hangers and wall tapestries or fringe tunics layered over brightly colored turtlenecks. It’s joyful, kitschy, accessible, and very beginner friendly. For all these reasons, it remains a popular textile tradition with devotees of all levels of skill and expertise. In all honesty, it is also a technique that has never particularly appealed to me as a textile artist. I had, in fact, been putting off reading about macramè in advance of our upcoming class with Cris Bertoluci. Then I started making lace, and my perspective on macramè changed completely.

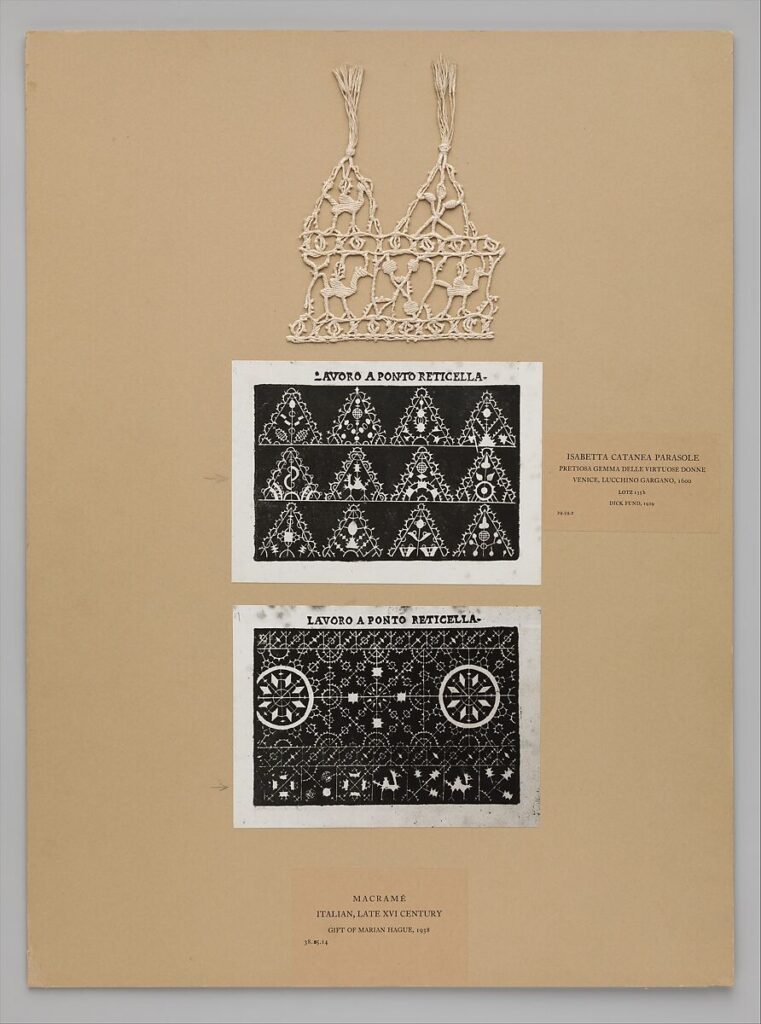

In a recent Tatter workshop on Irish Needle Lace, our teacher Fiona Harrington along with the lacemaker and historian Elena Kanagy-Loux were defining lace most broadly as a textile in which the pattern is defined by the spaces in between the threads. I asked later if macramé was lace, to which Elena replied without hesitation: “macrame is absolutely lace.” She spoke of 17th century Italian macrame, called ‘punto a groppo’ (knotted lace), an ancestor of bobbin lace, in which fine threads were knotted together to not only form patterns but also figures ranging from plants and animals to people in elaborate costumes. As I more closely examined the minute web of threads I had stitched carefully into my needle lace sampler and the looping picots between the knots I had woven with my tatting shuttle, I could see the same half-hitch knots, lark knots, and square knots which make up the most common macramé designs. My interest was piqued: I went to the library, pulled a few books, and started to read.

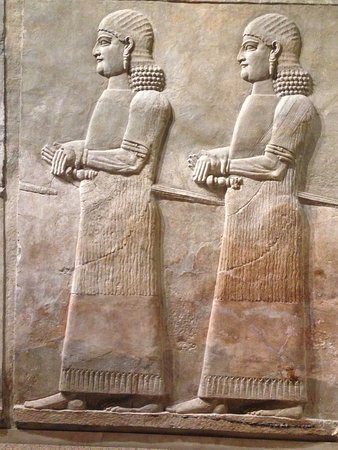

While the 70s certainly saw a revival of decorative macramé, the same basic knots we use today belong to an almost universal tradition that traces back at least as far back as ancient Assyria. Though most of the macramé we see today is an entirely knotted textile, often with a combed fringe at the end, historical examples had a much more practical purpose. When finishing a garment or woven textile, keeping the raw edges from fraying or unraveling is an important step in maintaining the longevity of the fiber. Even when properly cared for, textiles rarely survive from antiquity to the modern period. Our best look into fashion and fiber from thousands of years ago comes from art, such as this relief carving from the Assyrian citadel of Sargon II. The courtiers depicted are bare chested, wearing jewelry and long skirts decorated with knotted fringe (shown more clearly in an archaeological drawing of the symbols and tassels on the bottom of the garment).

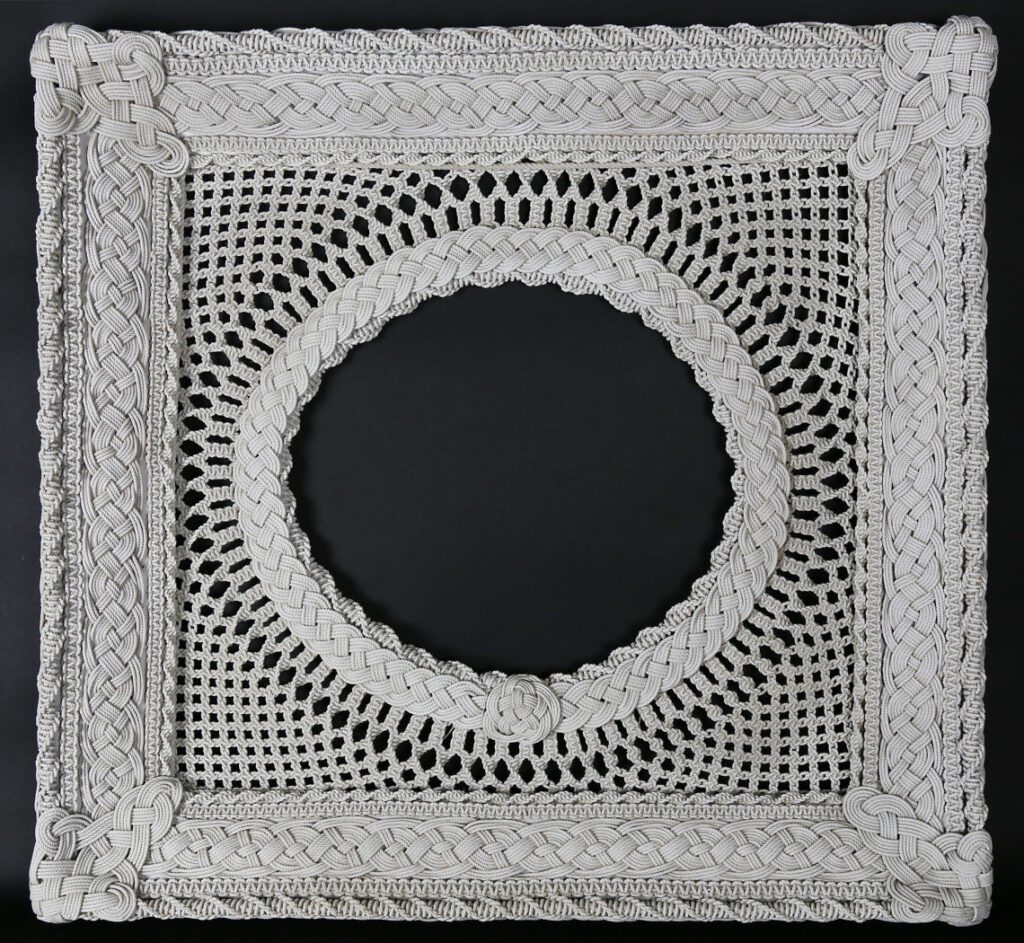

The word ‘macramé’ is derived from the Arabic word مكرمية (mikrama) which can refer to a towel, veil, or ornamental fringe. During the 16th century, macramé techniques became popular in Italy under the name ‘punto a groppo’ meaning ‘knotted points’ or ‘knotted stitches.’ Lacemakers spent painstaking hours bent over fine threads creating delicate scenes in tiny knots. The much thicker corded macramé of the 1970s did not really emerge for another couple hundred years, when it became a popular nautical pastime. Thick twisted cords were readily available on ships, and especially helpful when knotted into protective covers for bottles of rum which prevented them from shattering when dropped. Both military and commercial sailors spent long days at sea knotting bags, pouches, belts, baskets, needle cases, and even picture frames. When European sailors would dock in foreign ports, especially around China or Japan, they would often trade their crafts for local artisan goods.

Nautical style macramé enjoyed mild popularity through the mid 20th century. Sailor-style net hats, satin cord evening bags, and long silk shawls with long delicately knotted fringe designs all employed macramé techniques in their construction and design.

Then, in the 1960s and 70s, a convergence of countercultural movements brought the tradition into the mainstream. Feminist and textile artists challenged the binary of ‘fine art’ and ‘craft’, using techniques like macrame to make tapestries and sculptural works of art composed of both classic and unconventional knots. Hippies and the back to land movement, enchanted by the tactility and simplicity of the craft, began knotting belts, plant hangers, tunics, head bands, and curtains. Today, devotees of the ‘boho chic’ aesthetic draw inspiration from these mid century designs. Coastal beach houses, too, are filled with macrame lampshades with knotted hammocks swinging from porch ceilings.

In many ways, macramé is infinitely applicable. The same few techniques can be used to make a tiny strip of lace or a durable hammock that can bear the weight of three people (I know this from experience– my sisters and I have tested ours on more than one occasion). Whether you are intrigued but unsure how to start or experienced but in need of a refresher, Tatter will be hosting a virtual workshop on Macramé Basics with Cris Bertoluci on September 19th. I’ll be signing on to see how I can make this ancient art my own, and I would love for you to join me.

FURTHER READING AT TATTER

Macramé: the Art of Creative Knotting (1967) by Virginia I. Harvey. Call #: TT840.M33.H32

Beyond weaving (1974) by Marcia Chamberlain and Candace Crockett. Call #: TT699.C47

Introducing macramé (1970) by Eirian Short. Call #: TT840.M33.S47

Color and design in macramé (1967) by Virginia I. Harvey. Call #: TT840.M33.H33