During the Roosevelt Administration’s efforts to combat the Great Depression, the quilt became an emblem for how to lift one’s family out of poverty, piece by piece. On February 29th, Tatter will be hosting a virtual book talk with author and historian Janneken Smucker whose new book, A New Deal for Quilts, explores how the government drew on quilts and quiltmaking to encourage Americans to create quilts individually and collectively in response to unemployment, displacement, and recovery efforts. We spoke with Janneken about her personal quilt legacy, how she came to study quilts, and what quilt activism and mutual aid during the Depression can tell us about quilt activism today. You can sign up for the book talk here and read our conversation with Janneken below.

When did you first start quilting?

I learned to sew using my mom’s Kenmore sewing machine. One summer, when I was sixteen, I decided I wanted to make a quilt. My grandmother was a prolific quiltmaker, and I’m at least a fifth generation quiltmaker. My mom had a book on how to make a sampler quilt on her shelf from the early 80s with lots of different patterns and I grew up in a small town in northern Indiana where we would go to what was basically a five and dime that sold fabric. I just was mesmerized, I just loved the whole process of choosing fabrics and mapping everything out on graph paper. Then, when I was in college at a small liberal arts school I taught some of my friends to sew and set up a quilting frame at my college house. I studied history and women’s studies, though I still didn’t quite make the connection at that point that I could study quilts as my academic focus.

Did you have any favorite sort of interactions with the quilts and with the people you were studying?

I started this project in the spring of 2020. I had my first ever sabbatical from West Chester University and I had some grant funding to go on some archival museum visits, so I was really excited to dig in. Of course, none of that transpired. Luckily, I’m already a pretty digitally oriented historian. The amazing thing that happened was that women a couple generations older than me, women in their 70s and 80s who are renowned quilt scholars who don’t necessarily have the same academic background but who’ve been studying quilts for decades, sent me a box of research files in the mail. People would type up their research notes and send them to me. The generosity of these older women and their encouragement and support of this project was just amazing. There’s no way I could have done it, especially in 2020 when most outlets for doing research were shut down. It made me feel really connected, that I was clearly standing on the shoulders of so many other scholars, especially those who may not be as recognized by academia.

How do you balance being an academic and an artist?

That first pandemic year while I was on sabbatical there were all these terrible things happening in the world. I realized I needed to turn to my scrap bag, just as these women during the Great Depression did, and found that it was such a necessary respite. I started just sewing crazy style patch blocks. I’ve inherited bags of scraps from my mother and my grandmother, things I’ve picked up at flea markets, so I was essentially stitching together bits and pieces to make my own fabric then I would square them into blocks. It made me feel more connected to the women I was studying. Because it uses different parts of the brain, it’s very meditative and relaxing. So the making really helped complement the writing in that way. I always like to have some kind of project going on.

National Archives

1936

Speaking of scraps, where were people getting the materials that they were using to make these quilts?

As part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) there were governmental projects that were teaching quiltmaking. Women were making quilts in WPA sewing rooms to earn a living, and the government often supplied commercial cotton for their sewing. That was probably more so used as the batting for quilts, and then the scraps that were left from garment making in WPA sewing rooms were then also repurposed into quilts. Sometimes, those were quilts that were very utilitarian, whole cloth comforters that might have been tied or machine sewn together. One such quilt is in the Indiana State Museum, which is a rare find– it actually still has the WPA label. People who were making quilts at home to sell, for warmth, or for morale boosting were using a variety of scraps and sometimes the professional home economists, including those that were trained by the federal government, would teach them best practices for making quilts along with canning and gardening. There was a real promotion of reuse by those home economists. Women were being encouraged to use feed sacks and sugar sacks as well as the scraps leftover from making clothing.

Index of American Design

Elizabeth Valentine, 1936

Original quilt made by Elizabeth Van Horne Clarkson, c. 1930, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public Domain

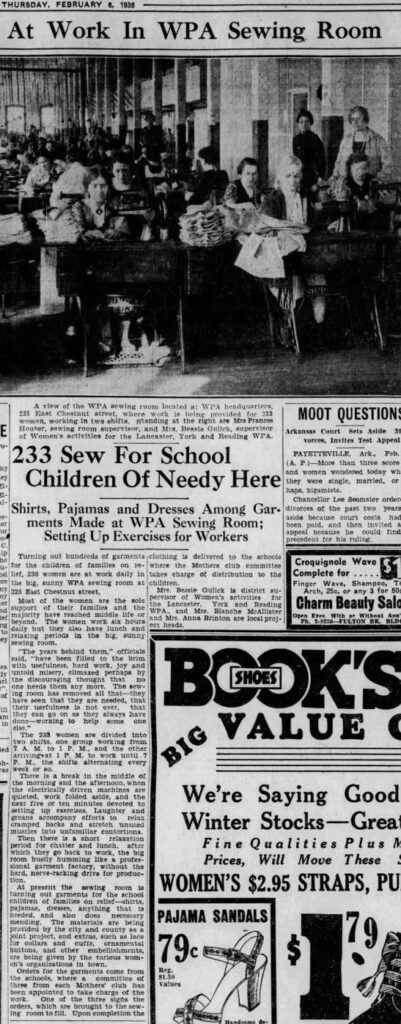

Lancaster Daily News, Feb 6, 1936

What was the primary goal of the WPA quilt programs?

Like most WPA programs, they were about lifting morale and they were about providing a paycheck. Women who were working in sewing rooms or doing handicraft projects would earn a paycheck, and then whatever was produced could not be sold– they were just donated to the needy. Sewing rooms produced millions of garments and probably hundreds of thousands of bedding items, including mattresses. It was mainly about supplementing income.

In the forties, fifties, and sixties quiltmaking in the United States really dropped off and we didn’t have a massive amount of consumer culture around quilting like we did in the thirties when every small town newspaper, every city newspaper, had a quilt pattern column and there were all these major quilt contests and so forth. All that stuff kind of dies down in the mid century. I think one of the things we can attribute that downturn to is people being tired of the drudgery of the sewing room. If you lived through that context, it would be a relief finally in the forties or fifties to just buy a bedspread from a department store. The next quilt revival really took off in the late sixties and seventies when people began making quilts again, and then it was fueled with all this nostalgia based on things like the Bicentennial and the back to the land movement. But I think one result of the quiltmaking of the Great Depression era is that we don’t have to make our own bedding anymore.

From what I understand, lots of textile arts have these generational skips. If you watch your mother constantly having to make quilts you may view it as oppressive but then your daughter looks at her grandmother’s quilts and romanticizes them.

This is exactly what happened in my own family. My mother made one quilt like when she still had young kids and wasn’t working outside the home, but she would say “that’s the last quilt I’m making.” She made maybe one or two others later on, after she retired, but when I started making quilts as a teenager I was definitely mainly looking to my grandmother for inspiration. During quarantine so many people took up lots of crafts, including quiltmaking, when they were stuck at home and it hasn’t really slowed down. There’s some interesting parallels to the Great Depression that when we are in challenging times and we need that morale boost in the 21st century, we’re building community over Instagram rather than necessarily in person, but still the same kinds of mutual aid are necessary.

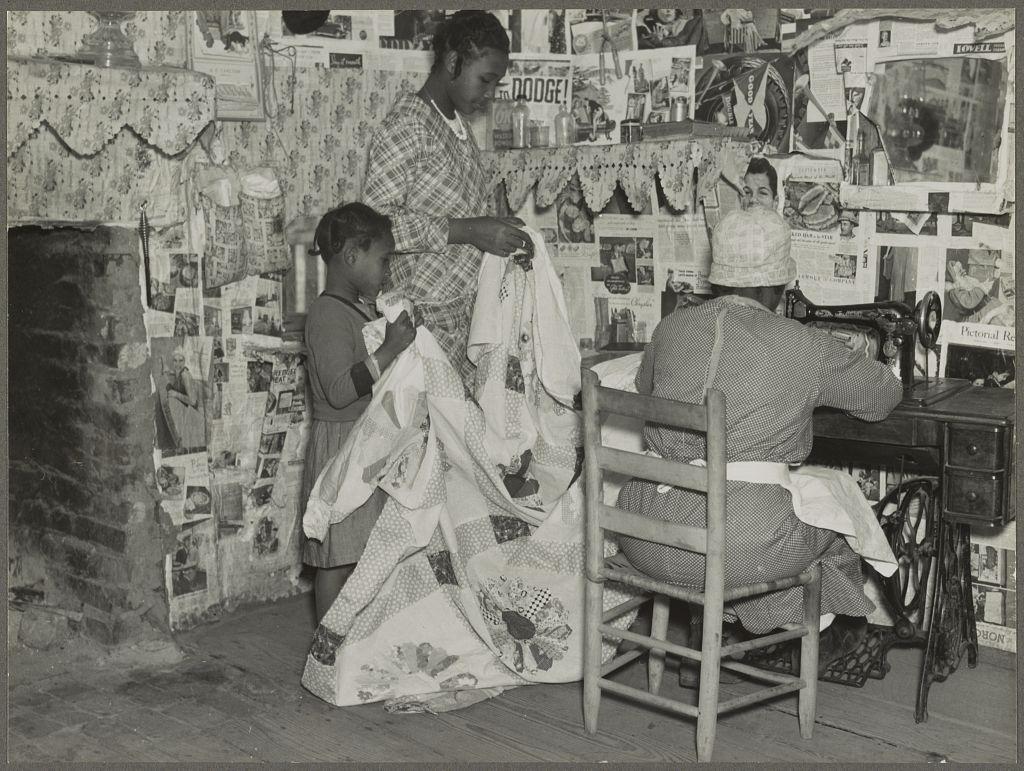

Arthur Rothstein, Gee’s Bend, Alabama, 1937

https://www.internationalquiltmuseum.org/exhibition/new-deal-quilts

Absolutely. I know that there’s currently a fundraiser for Palestine where a number of quilts are being auctioned off on Instagram.

There is a Mennonite action group that’s doing a bunch of demonstrations against the war in Gaza. They made all of these quilts to take to the United States Capitol. It was amazing to see quilts being used in that capacity. I mean, quilts have been used for lots of political and activist reasons but the Mennonites don’t generally do that. It was a real connection to my own upbringing and my own Mennonite heritage, seeing those images.

When you do get a chance to look at the book, you’ll see there’s so many kinds of activist quilts that were created by Americans expressing their frustrations, their political loyalties. There were hundreds of quilts sent to the Roosevelts as thank you gifts. Even though we think of this activism almost as more of a 21st century phenomenon, it certainly has its roots in American history. For example, the Tennessee Valley Authority quilts that were made by a group of African American women in the 1930s are so modernist. They look like nothing else out of the 1930s and they are really about expressing why African Americans are deserving of equality on these WPA projects.

What did you love most about building this book?

One of the things I love about the book is that it’s really beautiful. That’s in part because my publisher, the International Quilt Museum, really believed that we needed for it to be lavishly illustrated so it can serve as a coffee table book as well as a history. There’s well over a hundred images of quilts and then all of these amazing black and white photographs from the Depression. So if the idea of quilt history or history in general is daunting, forget the words and just look at beautiful pictures. They’re really inspiring, and you see real people, real Americans in these photographs. Living with quilts, working on quilts, posed with their finished quilts. It’s really inspirational.

Janneken Smucker is a fifth-generation quiltmaker, curator, and Professor of History at West Chester University outside of Philadelphia. Author of Amish Quilts: Crafting an American Icon (Johns Hopkins, 2013), Janneken lectures and writes about quilts for popular and academic audiences. She hosts and co-produces Running Stitch, A QSOS Podcast, in partnership with the national non-profit Quilt Alliance, drawing on oral histories with contemporary quiltmakers. She curated the exhibit, A New Deal for Quilts, at the International Quilt Museum, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, which accompanies the book of the same name.