In the late 1800s, a young girl received a Christmas gift. Like many around the world will do this week, she may have rushed downstairs on Christmas morning, excited to join her family in the opening of presents. Her other gifts may have included an orange, silk threads, or wooden toys. But the pride of her holiday haul may very well have been this velvet jewel. The pin cushion is small, the perfect size to fit cupped in the palm of a hand. Tiny loops of clear beads adorn the border, sewn onto the edge of a white panel of fabric. This fabric panel abuts the central motif, two large beaded leaves done in the same clear glass beads on a swatch of lush purple velvet. Their downward curves mirror the lobes of the heart above them. This style of beadwork is called raised beadwork, and consists of stringing more beads onto a length of string than can comfortably fit, causing the thread to buckle, and thus lifting the beads up from the foundation fabric. At the very center there is a small chain of beads, sewn down into a circle. The circle sits nestled in the leaves, the whole motif bordered by more chains of glass beads.

Sometime in the intervening century between when it was gifted and when it was purchased from an antique store in the late 2000s, the pincushion was inscribed with a short historical record. Inked onto the silk is a text in spiking blue cursive that reads:

By Ma – Presented to Effie-May Conger

Higginsville – Oneida – CoNy – Christmas Preasant [sic]

It is unclear what moved Effie-May, or perhaps her mother, to write down this piece of information, which we in the museum world refer to as “provenance.” It isn’t rare to find an antique object with provenance tips like this one. Many times there is much less, just a name or a date. Perhaps the most obvious example of this sort of provenance inscription is a caption on the back of a photograph, made in an effort against the fallibility of human memory. The Conger women seem to have been interested in this same preservation of memory, a testimony to their existence. They made sure that we knew they were here.

When I began exploring the TATTER object collections, I was immediately drawn to our pincushions. This pincushion in particular, with its inscription, made my eyes light up. It seemed like the most appropriate project for a person like me to take on, trained in archival research and with a proclivity for solving small mysteries. Armed with an expert’s knowledge of Ancestry.com and Newspapers.com, I started to look for Effie.

After an initial struggle with the thin, bleeding cursive, I phoned my father, who is much better at deciphering old handwriting than I am. We came to a consensus that it read Effie-May Conger from Higginsville. A google search told us that Higginsville is a small town, or hamlet, in Oneida County, New York. Using this biographical information, I was able to find Effie on a family tree on ancestry.com immediately. Much of her biographical information had been accumulated by other uses and quite extensively.

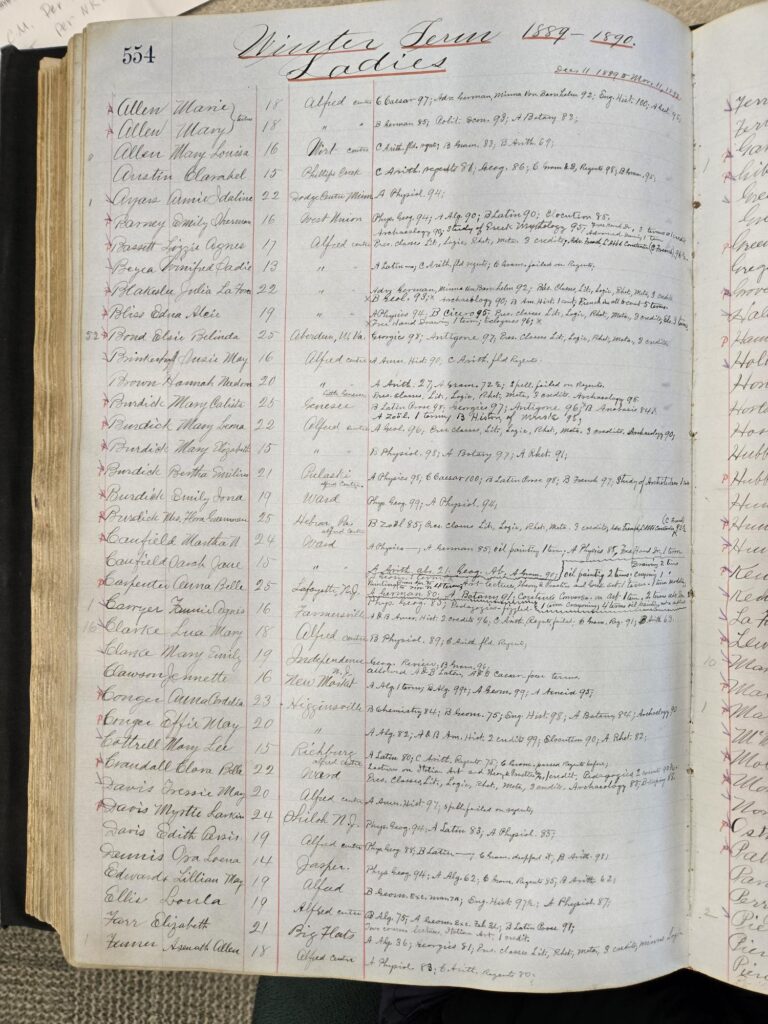

Effie was born on June 6th, 1869 to parents Jeremiah and Marion Conger. She lived in New York State her entire life, attending Alfred University from 1886-97, and then again in 1889-90. When it opened in 1836, Alfred University was the second co-ed university in the nation. The classes Effie took, arithmetic, grammar, rhetoric, elocution, foreshadowed her life long career as a teacher and later as a principal. On 25 Sep 1895, Effie May Conger married Ira Newey, a boy from her hometown, and became Effie Conger Newey. In 1898, they welcomed their first and only child, Elsworth Newey. Elsworth tragically died that same year, when he was only a few months old. He was buried in the New Union Cemetery, where he would be joined by his parents many decades later. Besides Effie’s time at Alfred, she lived no more than 25 miles from her childhood home her entire life. In 1950, five years after her husband’s passing, Effie died in her niece’s home, in the same town she was married.

I studied Native American Art History as an undergraduate, and spent the majority of my time learning and writing about Native beadwork. Because of this, I recognized several of our pincushions immediately as being Native made objects. More specifically, these pincushions are Haudenosaunee made. The word Haudenosaunee means “People of the Long House” and refers to the Seneca, Oneida, Mohawk, Tuscarora, Onondaga, and Cayuga nations of New York State. Together these six nations make up the Haudenosaunee. You may be more familiar with the outdated term “Iroquois”, which was a pejorative name given to the Haudenosaunee tribes by the French, an adaptation of the Alogonquin word for “rattlesnake.”

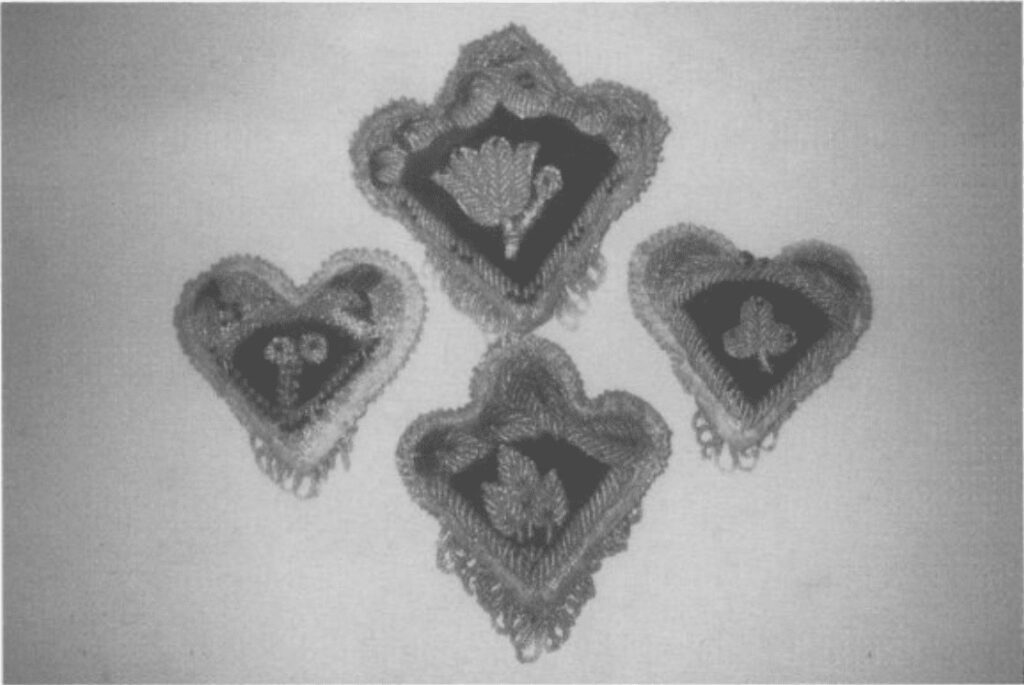

These Haudenosaunee beadworks are commonly referred to as “whimsies” by collectors. If you have frequented antique stores in the North East, you may very well have encountered many of them in your time. Whimsy pincushions consist of a fabric form sometimes velvet and wool or cotton, stuffed with pine shavings, sweetgrass, or some other filler. The forms are then covered in beaded floral shapes, or with a beaded slogan denoting the place or year of their construction. Pincushions come in dozens of forms: hearts, trilobed hearts, square pillows, scalloped edge pillows, and shields among them. Other kinds of whimsies can be found in the shape of birds, high heeled shoes, small purses, and wall hangings.

While beading had been an intrinsic element of Haudenosaunee artistic expression for centuries, the arrival of European trade beads on the American continent practically revolutionized the art form. Where it may have taken days to refine natural materials like stone and shells into beads, uniform and brightly colored beads were now immediately available. With production time slashed, artists now had more time to develop their visual languages. Unique styles blossomed, and the resultant beaded whimsies became a key factor of Haudenosaunee economic survival.

While very few Europeans had settled in Western New York before the Revolutionary War, the British loss encouraged an influx into the area. The Haudenosaunee, many of whom had fought on the side of the British, faced immense land loss from this new wave of colonialism. Those who had fought alongside the British were ousted from their lands, and forced onto a tract of land along the Grand River in Canada, near Niagara Falls. While the reservation era may have severely impeded on their traditional lifeways, the Haudenosaunee tribes found ways to preserve and adapt their practices to their contemporary lifestyles. While no concrete date exists, it seems that the advent of tourist goods began not long after their removal to reservations. As the century crept on, and Niagara Falls became more and more of a destination for tourists and honeymooners, it became an essential part of one’s pilgrimage to not only purchase a Native made souvenir, but to actually visit a nearby reservation. This problematic form of tourism was only an extension of the tourism to the Falls, an extension of the desire to see the “wild” and “untamed” natural landscape of the United States. For the white, Victorian mind, Native peoples were as natural to this landscape as the seemingly endless water that cascades over the Falls at 65 miles an hour, 700,000 gallons a day.

Historical records tell us that in the second half of the 19th century, Mohawk beadworkers made thousands of “hearts with purple velvet centers beaded in mostly clear beads [and] two leaves on the top of each pincushion”, and sold them on the banks of the Falls. That description sounds very familiar!

Like our pincushion, these pictured examples are constructed of two different fabrics, a purple velvet center, and a white fabric border. The fabrics are separated by the same border of three distinct beaded lines, two simple single bead strands, and a larger border of diagonally placed raised bead strands. While our pincushion does not have a large floral motif in the center, rather a small circle, it does have the two leaves, crowing the lobes. At the beginning of the 20th century Mohawk beaders began to favor hot pinks over purples. We can therefore assume that our pin cushion was most likely made between the mid 1800s-early 1900s. These dates line up with the information we know about Effie: born in 1869, her marriage and subsequent change of name in 1895. That gives us a 26 year window for when she received the pin cushion.

While the reservation era may have severely impeded on their traditional lifeways, the Haudenosaunee tribes found ways to preserve and adapt their practices to their contemporary lifestyles.

Despite the ubiquity of these objects on Victorian dressing tables, and their continued presence in North Eastern antique malls, very little was ever recorded about the lives of individual makers. Diary entries and letters from white tourists report seeing Native makers selling wares along the board walk to the falls (notably, the author Mark Twain remarked on their presence in his 1869 humoristic essay Day at Niagara.) But names of makers, dates of creation, and stories were rarely recorded by art historians, collectors, or tourists at the time. Perhaps one of the only exceptions is the story of Tuscarora beadworker Caroline Ga-ha-no Parker, who we are lucky to have a hefty record of her life and work. In most cases, information like this may only exist in family histories.

While we do not know the name of the woman who made this pincushion, we are able to construct a shaky outline of her life based on the information that is available to us. Judging by the similarities between this pincushion and the examples given above, she was most likely a member of the Mohawk Nation. She would have been taught beadworking by the other women in her family a young age, like many other Mohawk girls at that time. She may have sold her beaded wares to the various trading posts around the Falls, or she may have simply laid down a blanket near by the vistas and sold them herself, like many other women did. She may have had children, she would have experienced love and loss in her life, as Effie did. She beaded her velvet creations against the backdrop of some of the most pivotal decades in Native history. In 1871, the United States Congress approved the Indian Appropriations Act, which designated Native individuals as “wards” of the government, thereby eliminating their status as sovereign nations. In 1887, Congress passed the Dawes Severalty Act, which imposed private land ownership systems on Native tribes, a system which was completely at odds with traditional communal lifestyles. Native people were eligible to receive an allotment of 160 acres, usually the land was completely unfit for cultivation and farming. At the cessation of the allotment system, Native owned lands were reduced from 138 million acres to only 48 million acres by 1934. At this same time, the 1870-1890s saw a veritable explosion of artistic creativity from Native women across Native America. Faced with the forced “leisure time” of their new reservation lifestyles, Native women took to beads and threads. Styles were shared across tribal lines, and new forms of expression were developed, in the face of an imperial force deadset on eliminating Native life and lifeways.

At TATTER, we are no stranger to this loss of history. While our collections are full of the evidence of hundreds of women’s creativity and artistry, it is rare to have a detailed account of who she was, or what motivated her design choices. For centuries, the work of women makers, whether decorative or utilitarian, was often excluded from the artistic canon, deemed “naive” or “craft.” Native art has faced this same marginalization, for centuries it was collected by niche collectors, or displayed in natural history museums next to taxidermy and rock samples. The art of Native women has thus faced a compounding of these forces of ostracization. In recent years we have seen a turn in the overall Art Historical narrative, and strides to uplift and honor the voices of both historical and contemporary women and Native makers.

While we know little specifics about the maker of this pin cushion, it does not diminish the value of her work. In the face of ostracization, Haudenosaunee beadwork’s intrinsic cultural and historic value has never faltered. To this day, members of the Haudenosaunee tribes continue to create beautiful beadworks, incorporating traditional and contemporary techniques and styles into their work. Women’s Art History can often be a work of retroactive correction, and we hope that through explorations like this, we highlight the importance of these textile works, as they tell the story of an adapting, evolving artistic language, like the language of the Haudenosaunee beadworkers. This holiday season, may we reflect on the makers who came before us, and may we promise to do what we can to encourage the proliferation of their stories.

References

American Anthropological Association. “1870s-1890s: U.S. Control of American Indians.” NBCNews.Com, NBCUniversal News Group, 27 May 2008, www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna24714425.

Biron, Gerry. “Niagara Falls and Tuscarora Beadwork.” Historic Iroquois and Wabanaki Beadwork, 31 May 2011, iroquoisbeadwork.blogspot.com/2011/05/niagara-falls-and-tuscarora-beadwork.html.

Elliott, Dolores N. “Two Centuries of Iroquois Beadwork.” Beads: Journal of the Society of Bead Researchers, vol. 15, 2003, pp. 3–22.Gutierrez, Jeanne. “Indigenous Peoples’ Day: Honoring Caroline Parker, Haudenosaunee Artist.” Women at the Center , New York Historical Society , 8 Oct. 2021, www.nyhistory.org/blogs/indigenous-peoples-day-honoring-caroline-parker-haudenosaunee-artist.