I have spent roughly a decade studying the fashion designer Ann Lowe (c. 1898-1981), from a 2013 master’s thesis to, most recently, a 2023 exhibition at the Winterthur Museum Garden & Library. Yet, Lowe’s story and material culture can engage scholars for far longer. She had an eventful career designing custom gowns for some of the wealthiest and most socially prominent women in America and an even more fascinating life as a Black woman excelling and struggling in twentieth-century America. Learning about Lowe is inspiring. Viewing over 40 of her gorgeous gowns in one exhibition is awe-inducing. The expertly executed silhouettes, ranging from the 1920s through the 1960s, are set off by intricate details, especially flowers—lilies, poppies, roses—sculpted from fabric, appliquéd, beaded, embroidered, and hand painted. She was an outstanding designer and deserves to be remembered as such.

Lowe was born in rural Clayton, Alabama into a family of Black dressmakers. Her grandmother Georgia Thompkins and her mother Janie Lowe worked through the Reconstruction era and into the Jim Crow period, establishing a respected atelier in Montgomery. In a period when most Black women could only find work as sharecroppers, domestics, or laundresses, Lowe was trained as a dressmaker, beginning at six years old. If census records are correct, she married at the shockingly young age of twelve and gave up dressmaking at the insistence of her husband.

She came back briefly to finish an order of New Year’s gowns when her mother unexpectedly died in 1914. She also made her own clothes, and these attracted the eye of affluent Florida socialite Josephine Lee in 1916. Lee spotted Lowe in an Alabama department store and hired her to come work as her family’s live-in dressmaker just outside of Tampa. The courage and tenacity it took for Lowe to leave all she knew to pursue her dream of design is remarkable, made more so by her vulnerable position as a young Black woman and mother. Lowe recalled in the Saturday Evening Post in 1964, “when I told my husband, he told me to stay home. But I picked up my baby and got on that Tampa train.” She established herself as the city’s top designer over the next twelve years—an indispensable contributor to elite white society. Speaking years later of Tampa’s annual Gasparilla Festival—the event of the year made up of parades, balls, and a mock royal court of young socialites—one woman recalled, “If you didn’t have a Gasparilla gown by Annie, you might as well stay home.”

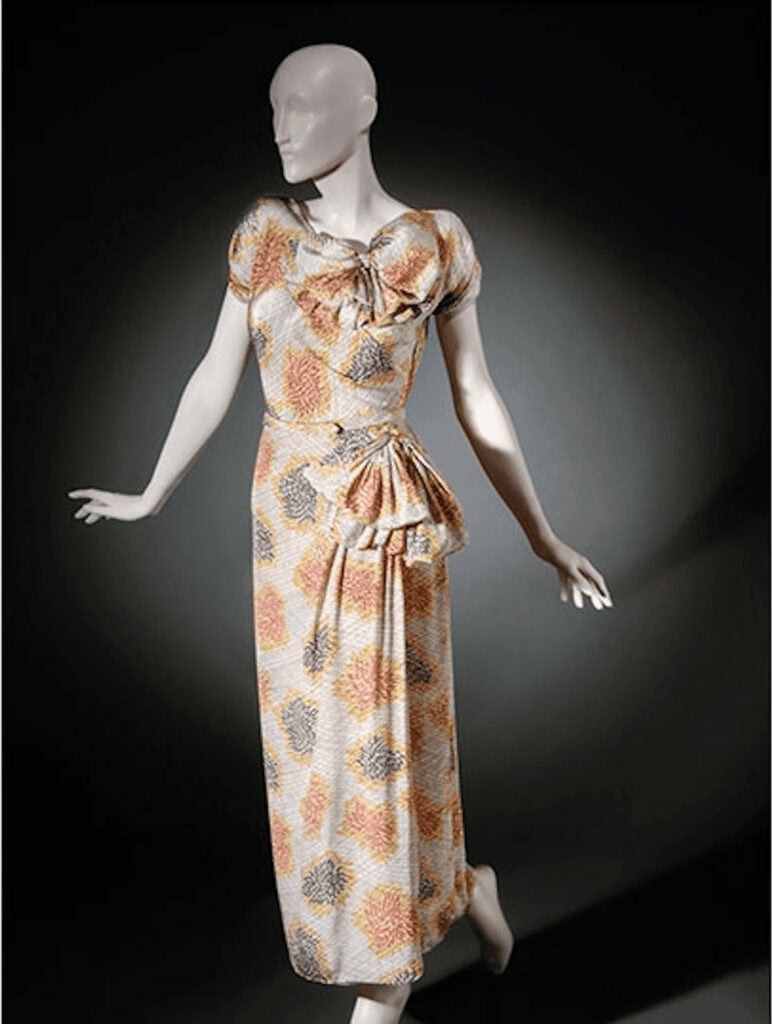

Even though she was successful and happy in Tampa, Lowe needed to test her mettle in the American fashion capital. She moved to New York in 1928. Lowe was committed to her creative practice and was consumed by the need to design. She spent the next four decades working in many aspects of the fashion industry—on commission during the Depression, for others including Hattie Carnegie, Sonia Gowns (1940s), and Saks Fifth Avenue (1960-1962), and for herself in many different shops. As a Black woman, she always needed white partners to rent spaces for her ateliers in the city’s Upper East Side—a crucial location to attract the clients she wanted. Lowe became an in-demand couturier, specializing in debutante and wedding gowns. Her work was feminine, intricately constructed and embellished, and made of the finest materials—on par with French haute couture. Lowe’s customers made up the upper crust of American society—women who made their debuts at formal balls, wed in the highest style, and were constantly photographed by the press. She was remembered as soft-spoken, dignified, and kind, putting nervous debutantes and brides at ease with her gentle manner and her beautiful, confidence-boosting gowns.

Although Lowe was appreciated, she was also a Black woman making her way through the complex social and racial dynamics of this elite group. As such, and as an American designer (not French), she received little press attention for her prominent designs until late in her career. Lowe loved designing, but her life and career were marked by annoyances—some of her rich clients bargained for unreasonably low prices; disasters—Lowe’s most famous dress, Jacqueline Bouvier’s 1953 wedding gown was ruined by a burst water pipe ten days before the wedding and remade in five; and tragedies—Lowe’s son Arthur, her faithful bookkeeper, was killed in a car crash in 1958. After that Lowe fell into tax arrears and lost her shop to the IRS while also undergoing a risky surgery to treat glaucoma. Her damaged eye was removed, and her sight continued to decline over the rest of her life. Despite setbacks, Lowe persevered. She designed thousands of stunning couture gowns, and by the grace of their beauty (and her clients’ wealth and connections), many of these are still with us today in museums from The Metropolitan Museum of Art to the Smithsonian Institutions and in private collections across the nation. These are fashion treasures that reveal layer after layer of the highest quality design and construction and the most beautiful embellishments and details. Her fabric supplier Arthur Dages stated, “Dresses are her art … If she had lived in France … she’d have been as well known as Chanel or Dior.”

References:

- Congdon Jr., Thomas B. “Ann Lowe: Society’s Best-Kept Secret.” Saturday Evening Post, December 12, 1964.

- Frye, Alexandra. “Fairy Princess Gowns Created by Tampa Designer for Queens in Gasparilla’s Golden Era.” Tampa Tribune, February 7, 1965.

- Major, Geri. “Dean of American Designers.” Ebony, December 1966.

- Powell, Margaret. “The Life and Work of Ann Lowe: Rediscovering ‘Society’s Best-Kept Secret.’” Master’s thesis, Smithsonian Associates and the Corcoran College of Art and Design, 2012.

- Way, Elizabeth, ed. Ann Lowe: American Couturier. New York: Rizzoli, 2023.

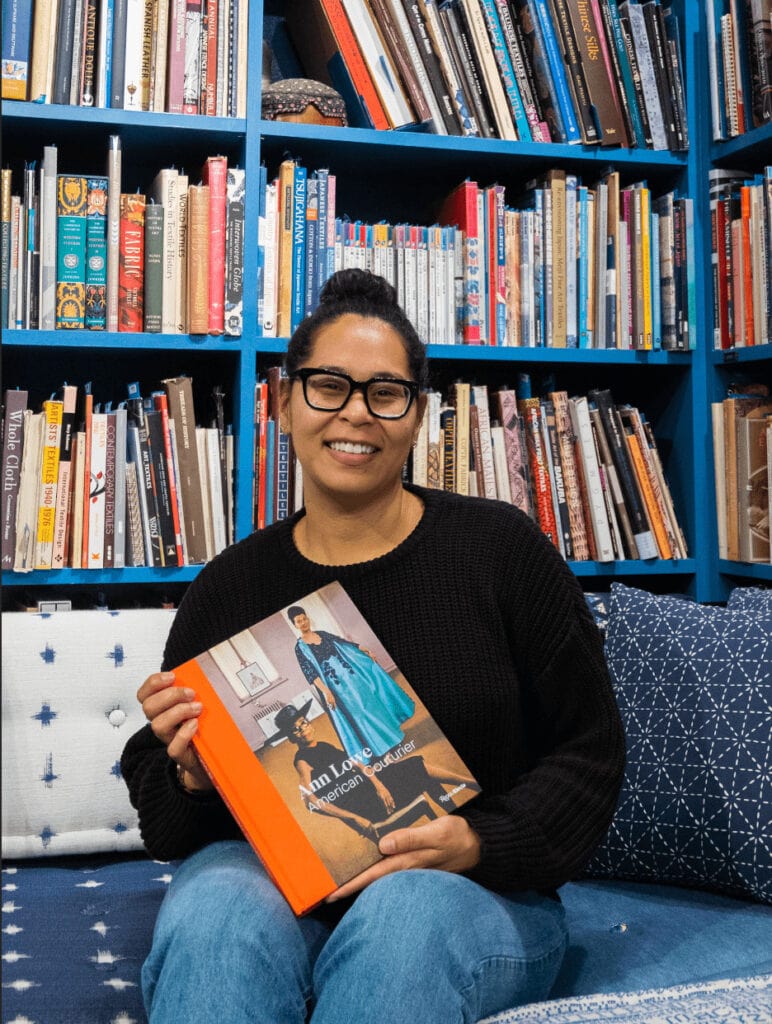

Elizabeth Way is an Associate Curator at the Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT), as well as a fashion historian whose personal research focuses on the intersection of Black American culture and fashion.

You can read more about Ann Lowe in our latest acquisition at Tatter: Ann Lowe: American Couturier by Elizabeth Way and Heather Hodge