In addition to being a necessary practice and source of income, people throughout history have turned to textile crafts and handwork in times of political, economic, and social instability. From Hmong people in Laos stitching story cloths during a genocidal insurgency, to American and British civilians knitting for soldiers in WWII, and, more recently, a huge turn to knitting and fiber arts during the Covid-19 pandemic, the meditative nature and tangible results of stitching have consistently allowed us respite from chaos. In many instances, textile arts have given agency, voice, and power to those who otherwise were without it. This phenomenon has well-studied psychological roots—planning and working through a project can create a sense of self-sufficiency and control, which are most needed in times of struggle and uncertainty. The repetitive motion of stitching is also a self-soothing action, calming overactive nervous systems.

The Common Threads Project, founded by Rachel Cohen in 2011, adapts these ideas into therapeutic practice by creating sewing groups around the world for victims of gender-based violence. Neurologic research has shown that the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for language and logic-based reasoning, can often shut down in the face of extreme stress, while more somatic instincts kick in. These traumatic events end up more closely linked to physical and visual processing than verbal, so talk therapy becomes more challenging and, often, less effective. Coupled with the psychology of hand making, these groups provide an environment where women with shared experiences can process what might otherwise be unspeakable, with the grounding repetition of stitches, and without the pressure of eye contact or direct confrontation. The efficacy of this system has driven the Common Threads Project to train therapeutic practitioners to implement their techniques in all sorts of settings.

Along with founder Rachel Cohen, author and psychologist Dr. Nicole Nehrig co-hosts a group with the Common Threads Project for survivors of domestic violence. Her recently published book, With Her Own Hands, details the history and experiences of women throughout history using textiles as a source of expression, empowerment, and economic independence. On October 23rd, join Nicole and TATTER for a virtual discussion of her new work! Nicole and Rachel will also be hosting an in-person event on November 1st: come join the slow stitching community gathering at TATTER in Brooklyn for a meditative, restorative experience!

Ahead of their upcoming events, Nicole and Rachel took the time to answer some of our questions about their work and textile practices.

What started your journey with textiles? Who, or what, drew you to them?

NICOLE: It was quite by chance. I was browsing around a hobby store when I was 26 and saw a teach-yourself-how-to-knit kit. I thought it seemed like something I could try to keep my hands busy so I bought it on a whim. I didn’t grow up around textile crafts. No one in my family did them when I was a kid. It was something I could do in my tiny NYC apartment, on the subway, and out with friends.

RACHEL: My immigrant grandmother taught me to sew when I was about 8 years old. In our healing circles, It’s amazing how I often hear about grandmothers (mothers are too busy for this!) who seem to be present with us as the members of the group are sewing. My grandma was a strong woman who endured a lot of hardship. She did needlework all the time. Embroidery, needle point, sewing, knitting, crochet. Looking back, I wonder about how much this probably allowed her to be so steady.

What most inspires your practice, both personal and professional? What drives you to continue creating?

NICOLE: The community I’ve developed around knitting and sewing is a big driver in my creative work. I now have many friends who knit and sew, and sharing our ideas and works in progress is a rich source of connection. I also find that making something tangible is an important counterbalance to so much of life in this technological age where so much is intangible.

What thoughts, memories, and/or emotions do textiles invoke for you?

RACHEL: I love that textiles can be soothing. Tactile comfort goes deep with us– think of a child’s blankie! I love that cloth is a cultural artifact that speaks of heritage and belonging. The scraps that we use carry visceral memories of people and places. Sometimes people make story cloths out of the clothing of a lost or disappeared loved one. There is such profound intimacy there. It does go to a place where words cannot.

NICOLE: I often remember what was going on in my life when I see and wear things I have made. It evokes the feelings I had at the time and can serve as an indicator of my growth. I recently wore a sweater that I made 15 years ago. It was the first sweater I ever designed. It made me think about how much has changed since that time – I had just started grad school at the time and now I’m many years into my career which I feel at home in, I’ve gotten married, had 2 kids, and feel so much more confident in myself as a person and as a knitter. I couldn’t have imagined when I made that sweater that this future version of me would exist and still be wearing it – at an event to promote my book, no less. These pieces mark moments in my life and show me how far I’ve come.

As artists who work both internationally and domestically, what are your hopes and concerns regarding the current political state? How do you see recent developments changing your work, if at all?

RACHEL: I am deeply concerned about where things are headed in the current political climate both here and abroad. My organization, Common Threads Project, has been affected by severe cuts to funding and the environment that has become hostile to humanitarian efforts. We are all terribly stressed out—and we use our stitching to pull ourselves together.

At the same time that we are facing shortages of resources to do our work, the need for our services has been increasing steeply: gender based violence, war, forced displacement, and persecution of the marginalized groups we serve has intensified everywhere. So we must find ways to persist.

At Common Threads Project, we are working to find ways to make healing accessible, effective, meaningful, and lasting. A bandaid impact is not sufficient. We envision healing for survivors of violence in the broadest sense—not just the absence of mental health symptoms (which is, of course, a start). We believe survivors deserve the restoration of their dignity and a full, productive life. They need to find a safe and affirming community, free themselves from shame and stigma, have access to their own creativity and find their voices—often they do this in cloth at first. Who could imagine that needle and thread could have this power?

Going forward, what do you hope to achieve through your work? Where do you hope to see it?

NICOLE: I am deeply concerned about the current political state and the backlash against women’s rights, LGBTQ+ rights, immigrants, etc… With Her Own Hands is an effort to humanize people whose humanity has often been outrightly denied and or overlooked. People disregard women’s work as a pedestrian activity or an expected part of a selfless way of being. A woman may make a quilt to keep her family warm but it is also a creative, social, emotional, and intellectual endeavor for her. A quilt is not just a provider of warmth and comfort for her family but a personal expression of self, and source of meaning for the creator. Recognizing peoples’ humanity is essential to combatting the dehumanizing effects of capitalism, fascism, and industrialization.

More broadly, I think that the simple act of making something tangible, real, personal, is a form of activism and an avowal of the humanity of the creator and the recipients of these gifts. I hope that we as a people can choose humanity over power, money, and technology. For me, making textiles is a way of expressing that choice.

SIGN UP FOR NICOLE’S VIRTUAL BOOK DISCUSSION

SIGN UP TO JOIN SLOW STITCHING IN PERSON

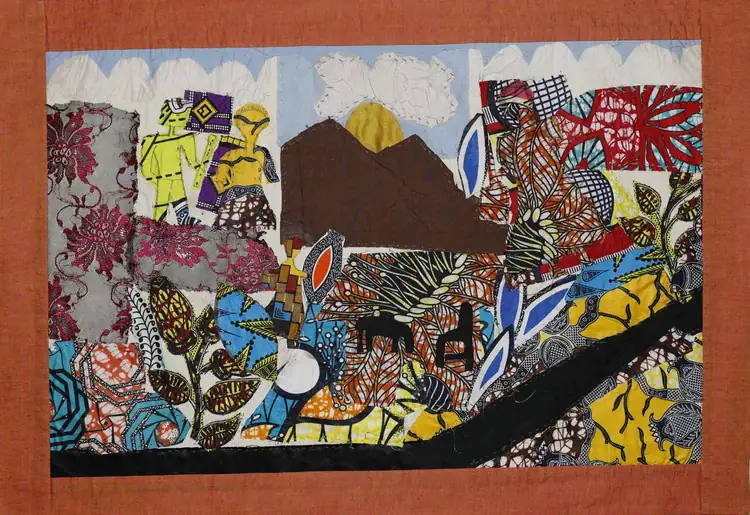

VIEW THE COMMON THREADS PROJECT GALLERY