For decades, librarian, scholar, and maker Wanett Clyde has used her hands to explore the intersection of Black history and fashion history. Her particular focus on the material culture of enslaved people in America eventually led her to probe the question, “What is a doll?” In a virtual lecture with TATTER on Wednesday, October 30th, Wanett will unpack this question through a survey of Black doll history, sharing historical examples, video, and photographs. She’ll shed light on the pitfalls of collecting Black memorabilia, offer insight into the current discourse on contemporary doll artistry, and present new perspectives on domestic crafts as art in public and private collections.

On December 5th and 12th, Wanett will join us again for a soft-sculpture class where students will learn the intimate, embodied practice of dollmaking. The pattern taught in this class is inspired by and named after Wanett’s Alabama-born great-grandmother, Eunice. The pattern pays homage to the quickly assembled doll babies that Wanett’s ancestors created using only the remnants they had on hand. Eunice’s endlessly customizable shape lends itself to the imagination of the maker. Dollmaking, like many textile art traditions, is greatly influenced both by who the doll is made for as well as its maker. Students will leave class with the foundational skills needed to create dolls that honor their own “Eunice” – the people important to them who shape their own stories and connection to making.

In advance of her lecture and class, we sat down with Wanett to discuss her personal relationship with dolls and how they relate to Black material culture and history. You can read our conversation and sign up for her lecture and class below.

How did you begin researching Black dolls?

When I was doing my graduate thesis on Black textile history during slavery, I found some of the few images we have of dolls from that era. It was a sweet thing that came up in a time where you don’t find a lot of sweetness, and that was what reignited my interest in dolls. When I was young, my great aunt Easter, my paternal grandfather’s sister, collected dolls. She had a pretty extensive doll collection, and it was always interesting to me at the time because she was not a parent and didn’t particularly seem to be a big fan of kids. She was not the warmest person, but she was a gifted seamstress. She made me a coat when I was little, and the lining had my name printed on it. When I was doing this research and thinking about the textile and maker history of my own family, I started thinking about her doll collection again. And then I started to want to try and make my own.

Did making your own dolls influence the way you saw the dolls you were studying?

I think what stuck out the most to me about trying to research the textile history of that particular period was how little remained. I was reckoning with the fact that so little remained because of the combination of the labors that people were expected to accomplish, how little clothing overall enslaved people had, and how low the quality was to begin with. It made me think about the lives of those people in a way that I don’t think I did as a younger person.

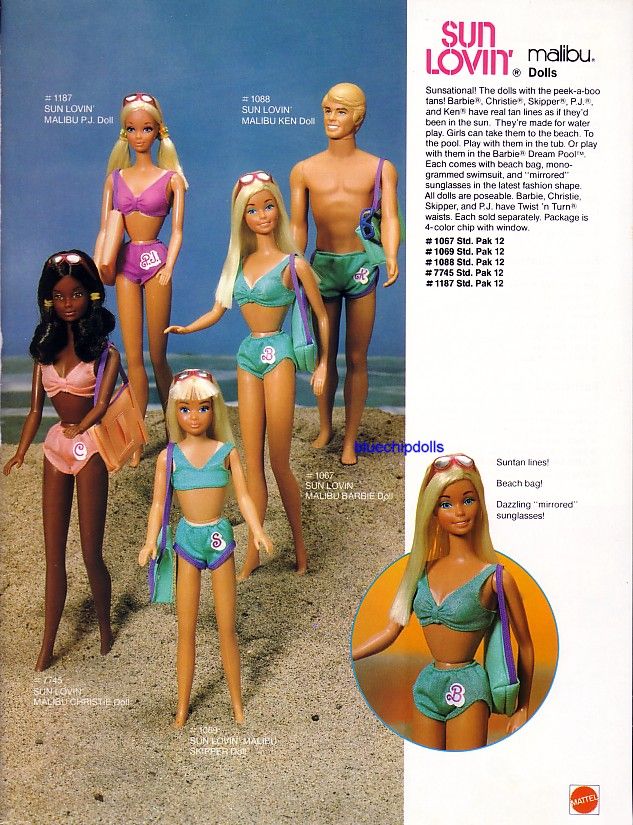

I also was thinking more about the history of Black dolls generally, including the last couple decades. Shonda Rhimes did this documentary on the origins of Black Barbie. I’m very good friends with an older Black woman who has children my age, and in our conversation about the documentary, in particular, she had said that as a young girl, nobody wanted black dolls. You didn’t want this sort of “consolation prize” doll. You wanted the Barbie that everybody else had. And so it was remarkable to her that the younger women in the documentary were a little irritated by that. We all had black dolls. My grandfather was the one who mostly purchased things for me. He liked the thrill of the chase, getting me something when it was popular. When the Cabbage Patch Doll had a viral moment, it was such a coup for him to get me a Cabbage Patch Doll. So he was usually the one that bought those kinds of things, and he never gave me white dolls. For my friend, who only wanted white dolls as a child, that was such a stark generational moment.

Some of the research that I’ve been doing in preparation for the lecture shows just how prevalent that attitude was. I found this blurb from a book called Racial Innocence, which is about who gets to be a child, who is allowed to play. There’s a story in a chapter about Black dolls where a woman is recalling this story about participating in a pageant where everyone got to present a doll and at the end, the best doll would be voted on. It was determined that she would get the Black doll because she was Black. She was clearly offended by this. Although she recalled so much about the details of the day and even the poem she improvised, she would not or could not articulate why she was so offended that she got the Black doll, or what was wrong with the doll.

It reminded me so much of my conversation with a friend, and how it is so different for her to watch her daughters be able to wear different types of hair to work. I have locs and I work in academia, her daughters wear braids, some women get to wear their hair buzzed or bleach blonde or under a wig. It’s also different for a Black woman of a certain age, particularly who worked in the corporate environment. To me, it’s all part of the same conversation. I have a real negative feeling for respectability politics, and the policing of Black bodies in particular, but it’s so much work to undo that. I’m not even sure that we ever could undo it, because it’s passed down generationally, and there’s still very real penalties for deviating from whiteness. It would be madness for me to say people should just wear whatever and behave however they want, because there are extremely real consequences for that which not everybody can shoulder. You can’t make the decision for someone else to be their absolute whole self but have a lesser salary or less prominence in their field. So it’s a lot to put on a doll. We can look back and problematize people’s reactions to dolls, but as Margo Jefferson said in Black Dolls, a doll is the only toy that is a representation of who we are. So with the woman telling the story in Racial Innocence – was she offended that the doll looked too much like her, or was she offended because it didn’t at all? And she was still being connected to the only other representation of Blackness in that space.

I wonder if it also had to do with the fact that this was a competition, and that there was no way that she was going to win with a Black doll.

It could be all of those things or some or none. It’s hard, because sometimes we can’t even say why. I think that we often have moments when we’re young, certainly for girls, where we covet something about another person’s appearance that is absolutely not possible for us to have without some sort of massive intervention, like hair relaxers for Black texture hair, or skin lighteners. There is always some desire for something that we don’t naturally have. And are dolls supporting that? Are they helping us reckon with what our own appearances are? That is way too much pressure for an inanimate object, bought or made. It’s a lot to put on a doll.

Being here with you as we look at the Black dolls in TATTER’s collection, having your experiences layered on top of your knowledge, is such a gift. It’s not just your academic knowledge, but also your lived experience and knowledge of textiles that heightens your ability to read these dolls. We’re grateful to have you present as we interact with and work to understand their significance.

I think what has impressed me about TATTER is that there is no rush to publicize. You take the time to be respectful of how they are addressed, how they are cataloged, how they are photographed. There’s so much rush today to be the first to do something or to present something. That’s where mistakes are made. For some organizations, they prefer to have the outrage reaction to something and then apologize rather than to take the time to avoid the outrage reaction in the first place. Some of that is marketing, but it’s mostly the ignorance of the people who are doing it. Being first doesn’t matter so much when what you could be showing is care. I think the thing that drives anyone who really studies material culture is love because there is so much love contained within these objects. They are soft, and very few of them were made to be overt displays. That creates a depth of importance to treating them with that same amount of love and care. The more I interact with people who study material culture, I see people who are so incredibly gifted make things of such beauty in homage to something from the past or as an attempt to understand it. In a small way making a new doll from a new pattern out of the newer materials is connected to the whole history of doll making.

I think that’s what interests me, it’s a very particular niche of material culture that you could just endlessly learn about. I’ve turned into a link saving machine, just thinking about all the things that I want to say and all the connections that I want to make. There are so many articles and photo collections, books, museum collections, and personal collections that are available because of the internet and social media. What’s cool about these kinds of talks is that sometimes you’ll have someone attending who didn’t come in with a particular interest in Black dolls or dolls in general, but something sparks their interest and it takes them further into it. That’s my favorite thing about all kinds of research. It’s why I’m a librarian. A little kernel of an idea can turn into an obsessive weeks-long deep dive. Sometimes it goes nowhere, and sometimes it becomes a lifelong project. The first time I thought this intently about dolls, I made the zine, and created the pattern. Now I’m doing this lecture and teaching this class and I applied for a grant to study a collection of Black dolls. Sometimes it just takes a spark.