When I met with McCall over Zoom, he was wearing a long chain of identical clear plastic buttons, one of his iconic button necklaces. It caught the light, reflecting prisms around his studio as he told me about his upbringing in Philly, his move to Harlem, and the evolution of his art over the past four decades. He describes himself as a “home grown talent” who grew up in a close-knit family in Philadelphia’s public housing projects. He learned to sew and create in summer camps and after school programs as well as from his mother and aunts. From the start, his interest was in fashion.

Today, people waiting for a train or passing him on the street do a double take: some even clip or rip a button off of their shirt or jacket and hand it to him. He’s known in Harlem and throughout the city as Sir Buttons, Count Buttons, or ‘The Button Man.’ People don’t just spontaneously give him the buttons off their clothes, they send him whole collections in the mail or bring bags of buttons to give him personally at his shows. In interviews, he says that buttons are the universal fastener which connect the world, and for McCall that isn’t just a turn of phrase. His buttons have come to him from all over and taken him far outside of Harlem. At the end of March, McCall and his buttons will travel to Brockton, Massachusetts for his first ever career retrospective.

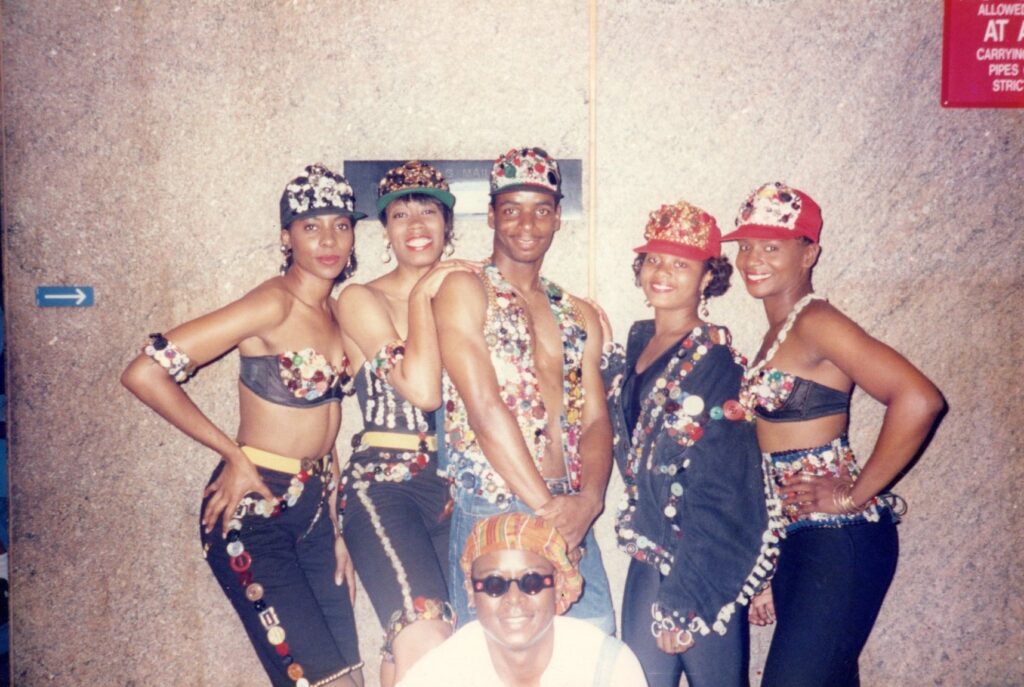

Photograph of actor Michael K. Williams in wearable art by Beau McCall backstage at the 11th Annual Monarch Awards at Sardi’s Restaurant in New York City, 1991. Photograph by and in the private collection of Beau McCall

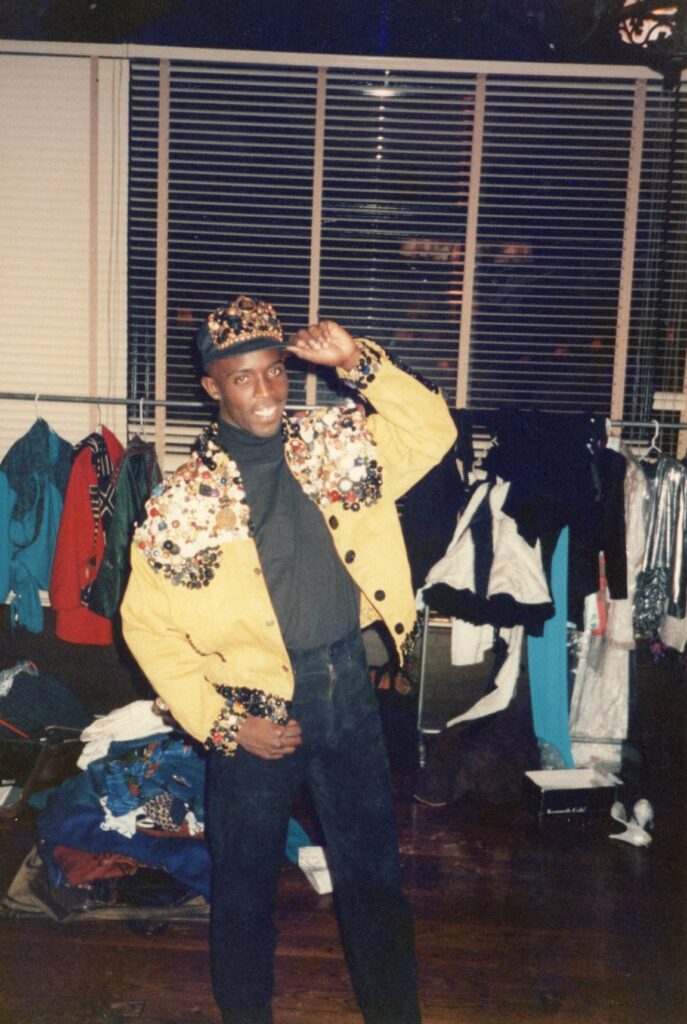

Photograph of Beau McCall wearing his button sweater creation, 1989. Photo by Larry Naar. Private collection of Beau McCall.

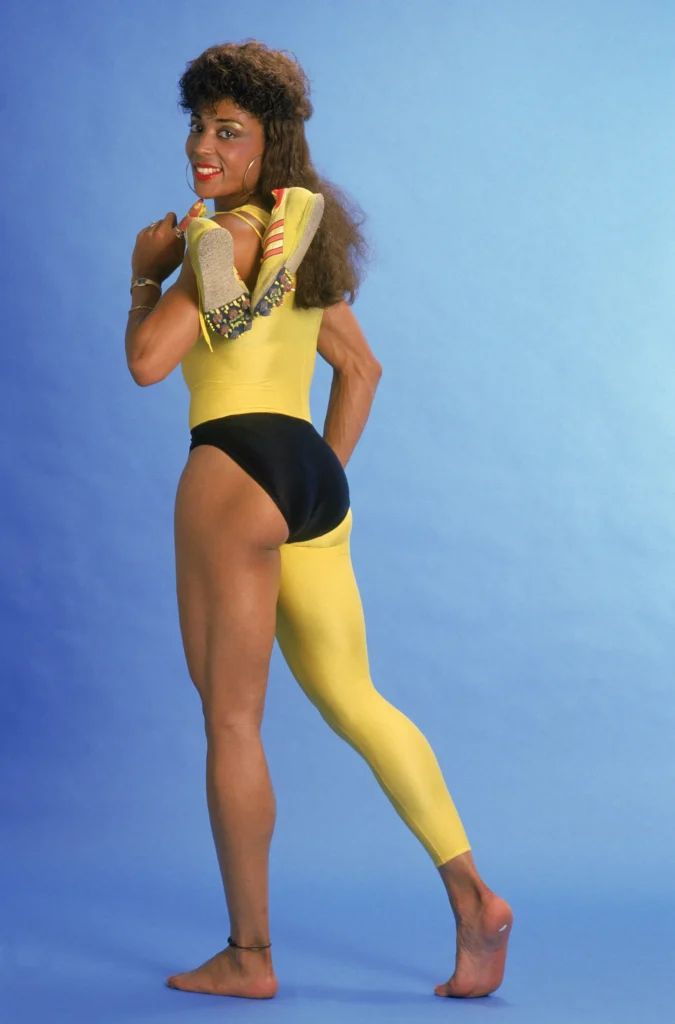

World and Olympic athletics champion Florence Griffith-Joyner of the United States (1959 – 1998) poses for a portrait on 5th April 1988 in Los Angeles, California, United States. (Photo by Tony Duffy/Allsport/Getty Images)

The early 70s was a time for innovation in fashion: the DIY ethics and repurpose sensibilities of the punk movement and other alternative scenes inspired McCall and his high school classmates to experiment with their own styles. He was cutting up his clothing, tie-dying his t-shirts, attaching studs to his jeans which would rip his socks to shreds as he took them off.

“I just had that bug in me,” McCall said, laughing and shaking his head, “remember what Flo-Jo used to wear? That track suit with one leg? I was doing that when I was like 13. She probably wasn’t even born.”

McCall, of course, still works with recycled clothing. His wearable art line ‘Triple T-Shirts” upcycles three (sometimes more) T-shirts into one seamless flowing garment that can be configured to be worn in six unique styles. He mixes and remixes clothing and loves going to thrift stores, junk shops, and consignment stores. That’s also where he sources most of his buttons– the ones that don’t come to him by way of friends, family, and admirers.

Souleo and Beau McCall, right, at the opening of “Fresh, Fly, Fabulous: 50 Years of Hip-Hop Style” at the Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology. Credit Krista Schlueter for The New York Times

The first button piece he ever made was as a teenager in the early 80s: a knit sweater vest which he covered in buttons before going to a disco. The end result was so heavy that the knit stretched and hung down to his knees.

“I didn’t have a technique. I didn’t have a style,” he told me, “all I knew was I had this jar of buttons before me and I was ready to create something.” Later iterations of the button vest (such as the one pictured left, from 1991) were sewn onto much sturdier denim.

In 1987, McCall left Philadelphia and moved to Harlem– as he tells it– with “only $200 and a handful of buttons” in his pocket. In 1988, he made his wearable art debut at the Harlem Institute of Fashion show for HARLEM WEEK to critical acclaim. A friend had called to tell him about the auditions, remembering that he had been working on “all those button pieces.” So McCall gathered up his upcycled designs and took them to the Harlem Institute of Fashion where he was interviewed by Jorge Saunders. After looking through the collection of button covered clothing, Saunders asked McCall how soon he could start. McCall replied he could start immediately.

The day of the first show was a triumph. “It’s the first time that I had seen a fashion show of that magnitude,” McCall remembered, “with 1000s of people watching this show in front of the State Building. It was all black folks. It was all black models. It was all black designers. It was all black administrators, and it was all the brainchild of Lois K. Alexander-Lane.” Even then, thirty-five years later, McCall was glowing at the memory. “It was like I found my creative tribe. I was just newly from Philadelphia, and the only people I knew were the people that I worked with. It was a very rich experience because we were out and about doing these shows and meeting like minded people, meeting creative people. So it opened the door for me to venture out elsewhere and connect with people.”

Beau McCall’s “Button Vest: Caramel Crayons” one of twelve works highlighted for Martin Luther King Jr. Day at The Rhode Island School of Design Museum. Wheeler Copperthwaite/The Providence Journal

McCall shone at Harlem Fashion Week. The buttons on his clothing were bright, reflective, flashy, exciting. He was invited back every year through 1995 and was featured in their museum exhibitions and prestigious events. While his impeccable style and wearable upcycled art remains a key part of his practice, McCall’s sculptural visual art is spectacular and moving in a whole other way. Commissioned by Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, one of McCall’s most recent works is an assortment of clothing buttons on cotton fabric molded around a cast iron tub.

Beau McCall, darkmuskoilegyptiancrystals&floridawater/redpotionno.1, 2014. Assorted clothing buttons (mother-of-pearl, rhinestone, cloth, et al.), embroidery thread, cotton fabric, cast iron tub, 53 x 17 x 23 in.

In McCall’s own words, the piece is “inspired by the poem one from Ntozake Shange’s choreopoem, for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf. He depicts the climax of the poem when lady in red, after giving herself to a lover–and cycling through emotions of possible regret or ambivalence–prepares a bath to wash away his scent and the glittering elements she uses to adorn her body. Thereby, McCall’s imagining of this bathtub becomes a spiritual and ritualistic sanctuary and site of one’s search for inner peace and self-love.”

When asked about his technique, McCall referenced another of his pieces, ‘World Spinnin’ on a 45 (B-Side), 2023.’ The first layer of the piece uses his ‘webbed’ technique where embroidery thread is woven not only through the buttons, but also on top of them, to create a weblike pattern, simulating the grooves on a worn record. The bottom layer is uniform, yellow buttons, with various decorative buttons on top. “It’s about unifying people through music,” he explained, “so I use buttons shaped like shoes for dancing, I use peace signs, I use anti war signs. I used musical instruments, musical notes. So the buttons speak within the piece. Sometimes you’ll have to sit there and just read through all these buttons to get the theme and the narrative of what’s going on in the piece. So that’s why buttons still stick with me today. because every time I do a new piece it dictates a new set of buttons. It’s not like I’m using the same tools over and over and over again. It’s a unique set of materials to come with with each project. So that’s what keeps me energized, keeps me interested.”

To close out our conversation, I asked McCall about his inspirations. His answer will be no surprise to any fans of the artist. In almost every media feature of the Button Man (and there are many), he makes a point to celebrate his mother’s role in his work. “My mother is my biggest inspiration,” he told me, as he has told countless interviewers before. “I learned a lot from just watching her decorating the house, her color combinations and her power to stay focused and believe in what she was doing. She has always believed in me 200% and she still does. Years ago, I called my mom and said ‘I’m stuck right now, I’m working on something and I don’t know what to do.’ And she just said out of the clear blue: ‘just stack the buttons on top of each other.’ I hung up and I stacked maybe 10 buttons on top of each other across to get this Mohawk effect. So my mother is my biggest inspiration.”

Forty years in, McCall doesn’t know where most of his buttons have come from. People on the street, people at his shows, family, friends, junk shops, strangers who send envelopes and boxes and bags in the mail. Someday, he is confident, they will all show up on a piece of art. If you have ever given the Button Man a button, you should be sure to check out his retrospective Buttons On!— you may even see a piece of yourself reflected under the museum lights.

Buttons On! marks the first-ever retrospective for creative artist, Beau McCall. Proclaimed by American Craft magazine as “The Button Man,” McCall creates wearable and visual art by hand-sewing clothing buttons onto mostly upcycled fabrics, materials, and objects. Buttons On! showcases pieces from McCall’s nearly forty-year career, the debut of several new works, and select archival material. Organized into several themes, the exhibition explores McCall’s mastery of the button and commentary on topics such as pop culture and social justice.