Edith Wyle (1918-1999) was an artist, arts patron, and co-founder of the Craft and Folk Art Museum (CAFAM) in Los Angeles. Carol Westfall (1938-2016) was a fiber artist, avowed feminist, and professor of textiles. Glee Krueger (1931-2018) was an embroiderer, lecturer, and needlework collector. These women were also published authors. Edith penned several museum texts during her years as CAFAM’s program director; Carol co-authored a book on plaiting; and Glee produced two pioneering works on the history of American samplers. Over the course of their colorful lives they amassed book collections that reflected each of their unique passions for global textile art, traditions, history and culture. Their books graced their homes, documented their travels, inspired their careers, deepened their craft, and were beloved extensions of themselves. Each of their families felt strongly that preserving and sharing these collections was tantamount to honoring the life and legacy of their owners. Their volumes, accompanied by a selection of their objects, now stand together within our ever-growing library.

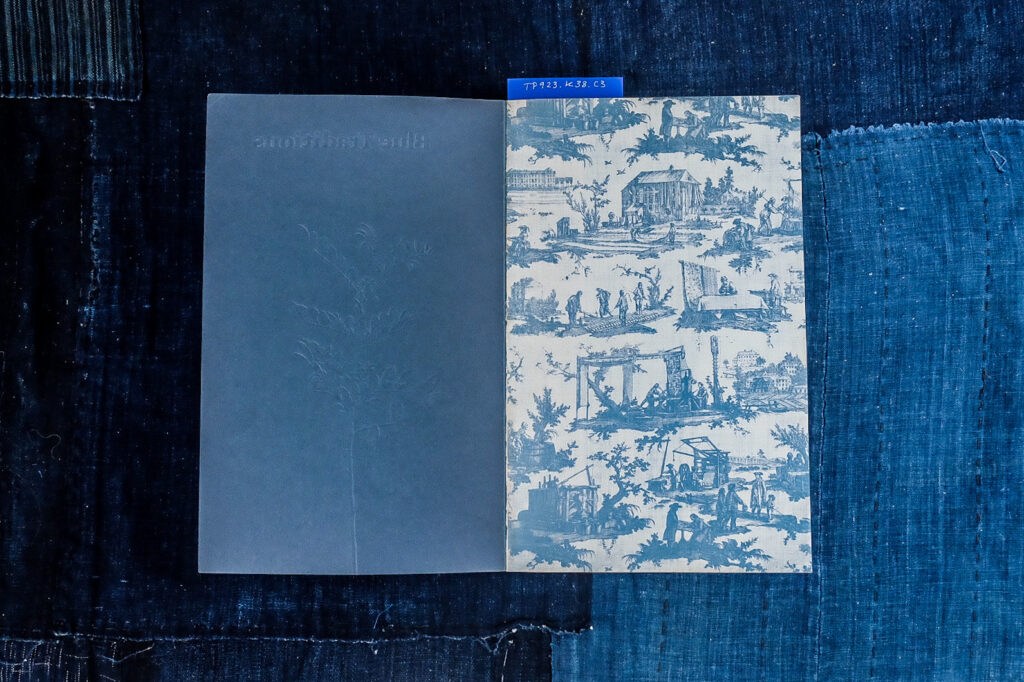

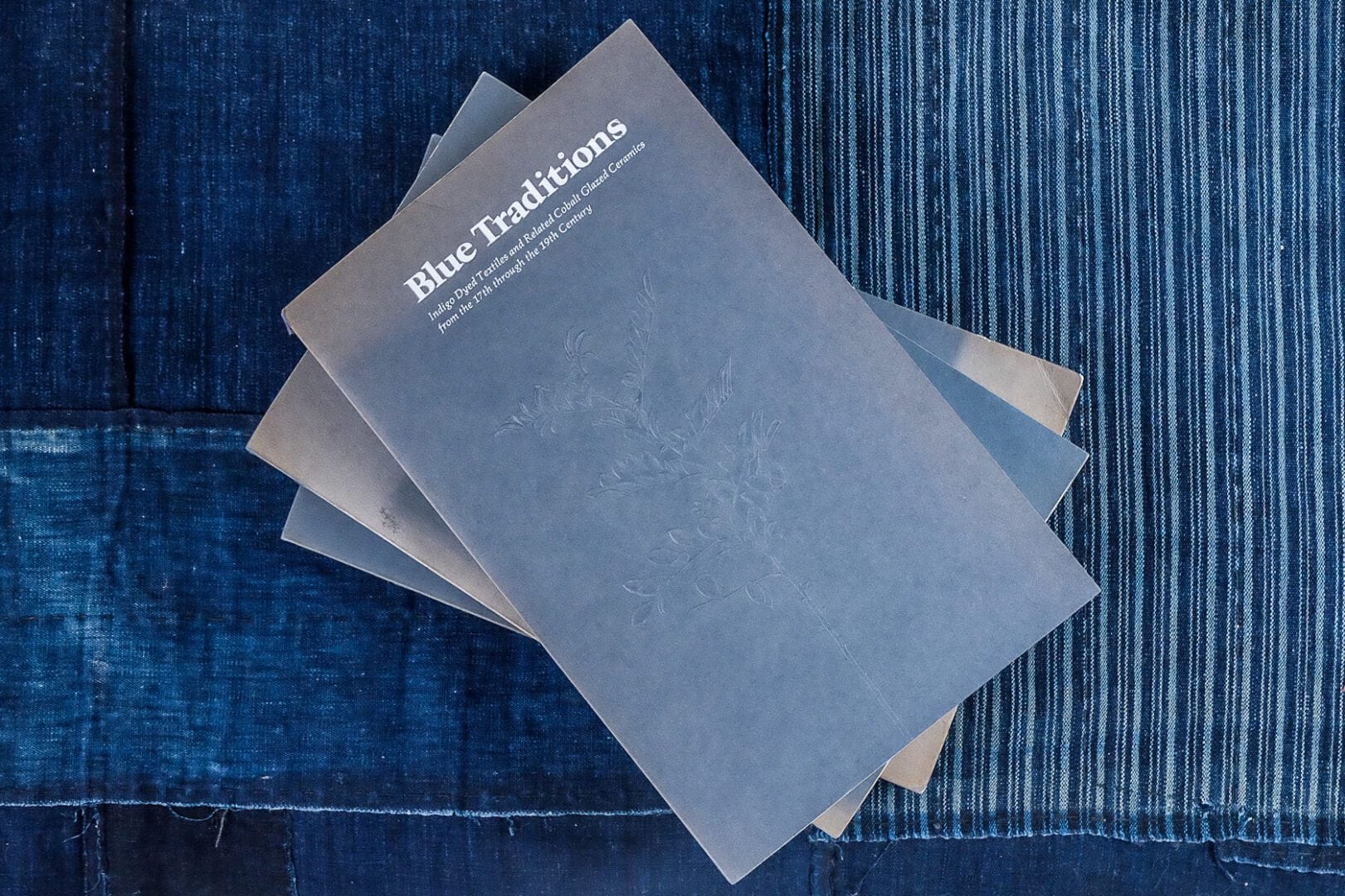

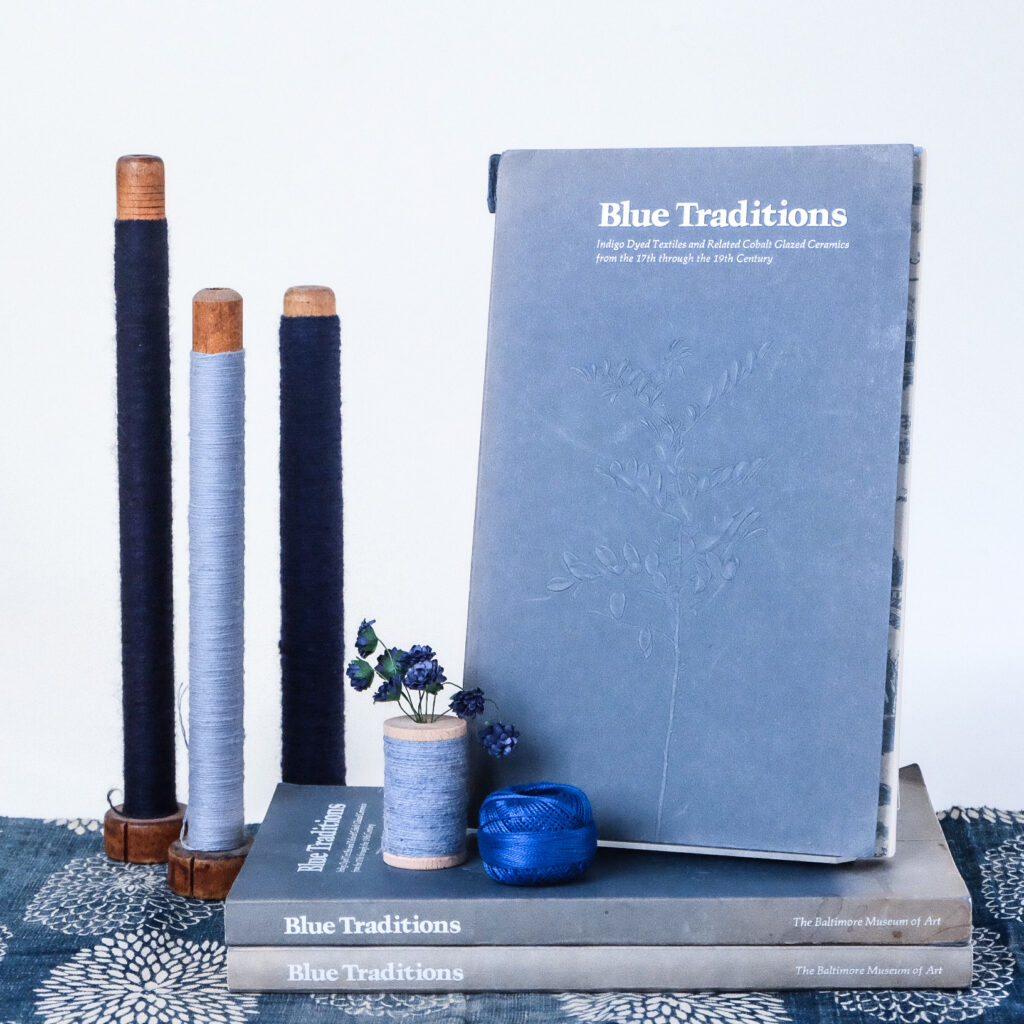

While there was some duplication of titles across the three collections, one volume was common to each. Blue Traditions: Indigo Dyed Textiles and Related Cobalt Glazed Ceramics from the 17th through the 19th Century is an exhibition catalog published by the Baltimore Museum of Art in 1973. TATTER Founder and Director Jordana Martin has held this book dearer to her than most, as it so perfectly anchors and encapsulates the mission of BLUE. It lends weight and continuity to the idea that our fascination with blue is universal, and that blue within the context of textiles is particularly remarkable and deserving of our attention.

In the preface, Dena Katzenberg writes that in addition to understanding the history of indigo cultivation, manufacture and trade, “we may also wonder at the intense focus of a single color idea, and why it appears to have such importance.” Katzenberg writes that 17th century Europeans were enchanted by the novel beauty that indigo and cobalt brought into their lives. The popularity of Chinese blue and white porcelain cultivated a desire for a blue and white color scheme in European textiles, which was made possible with the arrival of indigo in Europe. She argues that indigo textiles and cobalt ceramics thus reinforced each other’s popularity and contributed to the “rage for blue.”

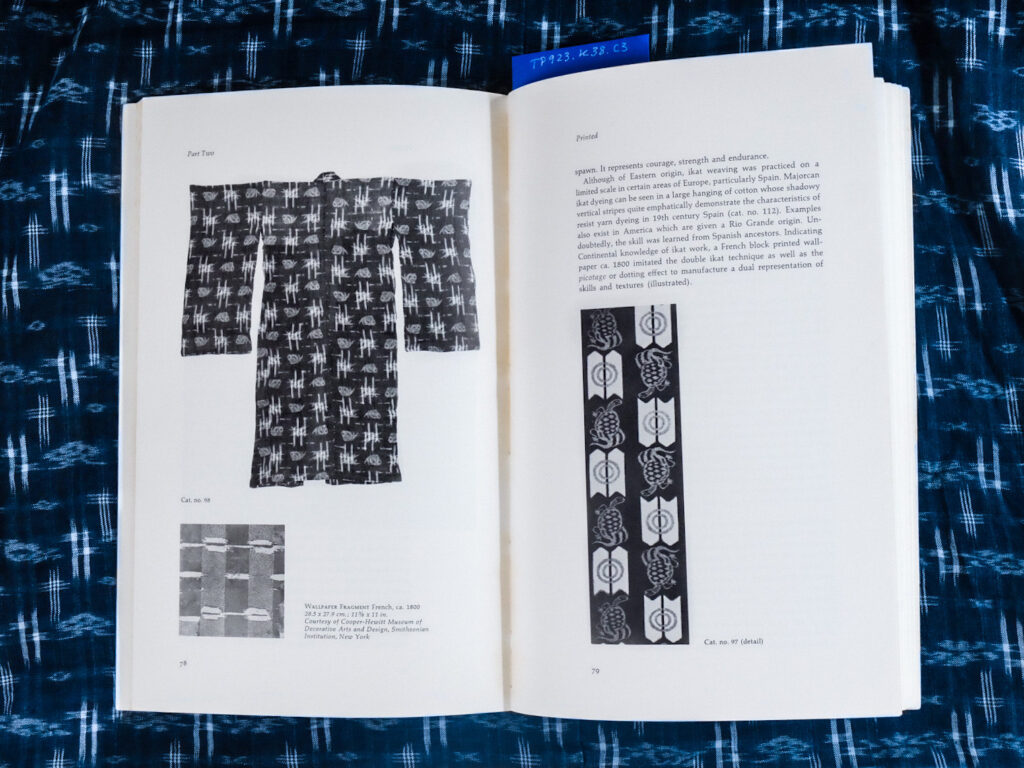

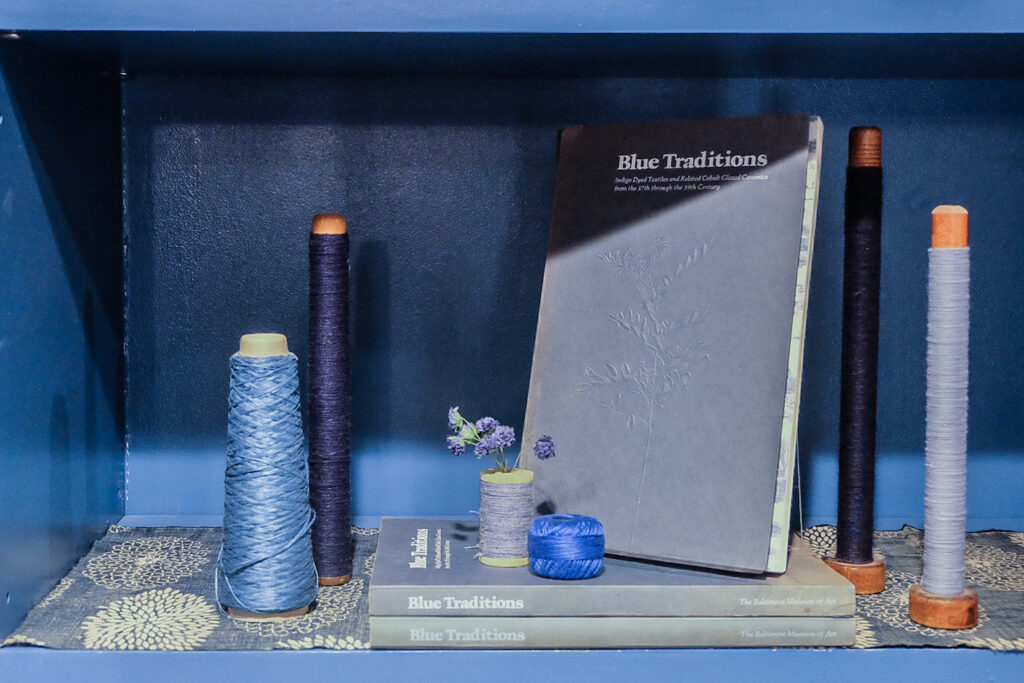

Despite the subject matter, the catalog of blue objects is printed in black and white, leaving one longing for the “brilliant blue” written about by Katzenberg. Opening the book within the library, however, gives heady life to the text, as readers are immersed in a rich blue space of varying hues. While describing the alkaline vat required to yield indigo’s blue color, Katzenberg writes that the “lengthy and demanding procedure is most rewarding in that the resultant color can be both vibrant and permanent.” Likewise, we like to think of the library space as a sort of vat process, a surprising and joyful immersion, a place to contemplate both tradition and possibility.

The fact that these three women prized Blue Traditions felt like a cosmic nod that their volumes belong here and together, the union of their books a sort of homecoming. While we typically only keep one copy of each title on the shelf, the three Blue Traditions sit shoulder to shoulder alongside others on the subject of indigo.

Edith of California, Carol of New Jersey and Glee of Connecticut never crossed paths in life, but they undoubtedly would have found thrilling the textile conversations that their books now kindle.