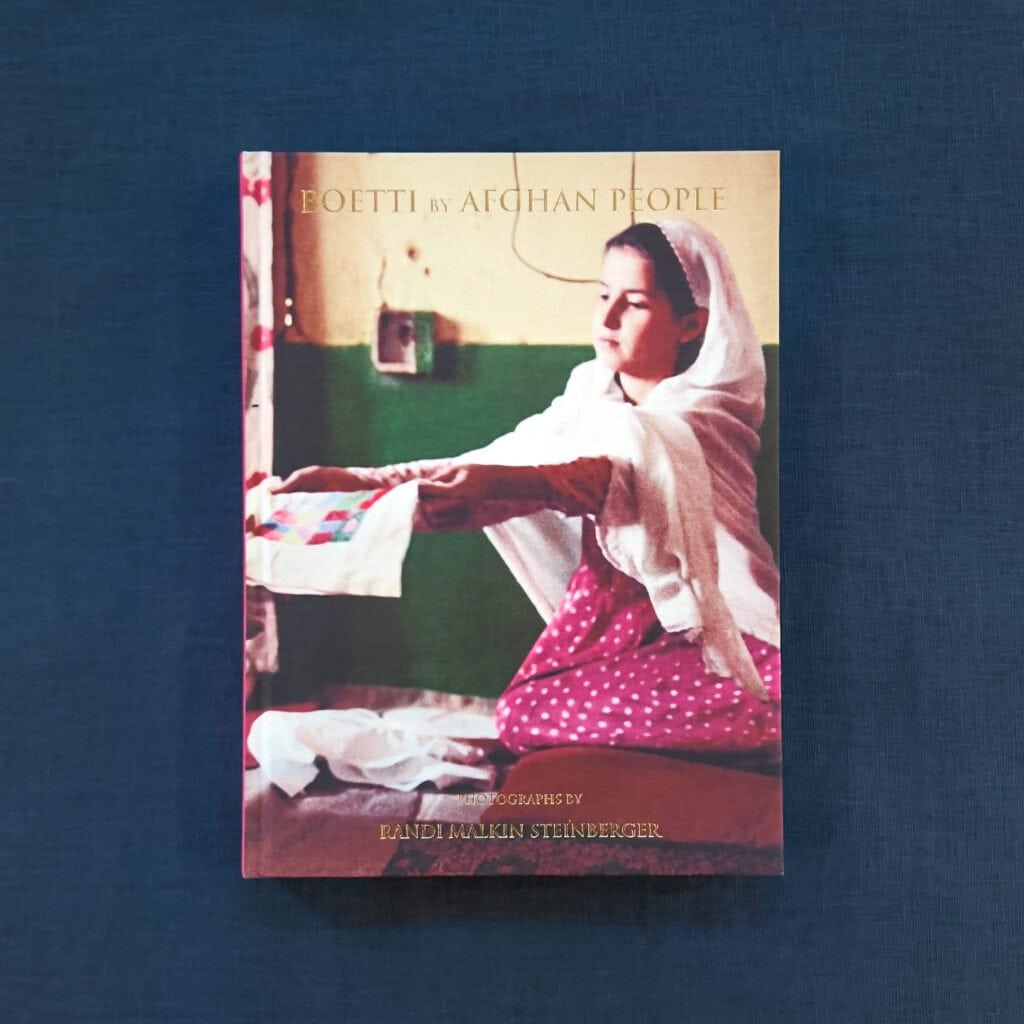

Boetti by Afghan People by Randi Malkin Steinberger is one of the many delightful discoveries that came to TATTER with the Carol Westfall Collection. Carol Westfall (1938-2016), an internationally-renowned fiber artist and professor, was clearly drawn to the Italian conceptual artist Alighiero Boetti and collected many of his monographs, including this one. The book is striking both for its provocative title and cover image of a young kneeling girl offering up a piece of colorful embroidery. When I cataloged TATTER’s foundational collection of books back in 2016, I was surprised to find that other libraries placed this book in the Afghan embroidery section rather than with other monographs by Boetti. Once I dug into the story, this made total and poetic sense. The story behind Boetti’s arazzi (embroidered works) is the kind we love to unearth and share here at the library: one that focuses on the hands that work textiles into being, the complex humanity behind the cloth.

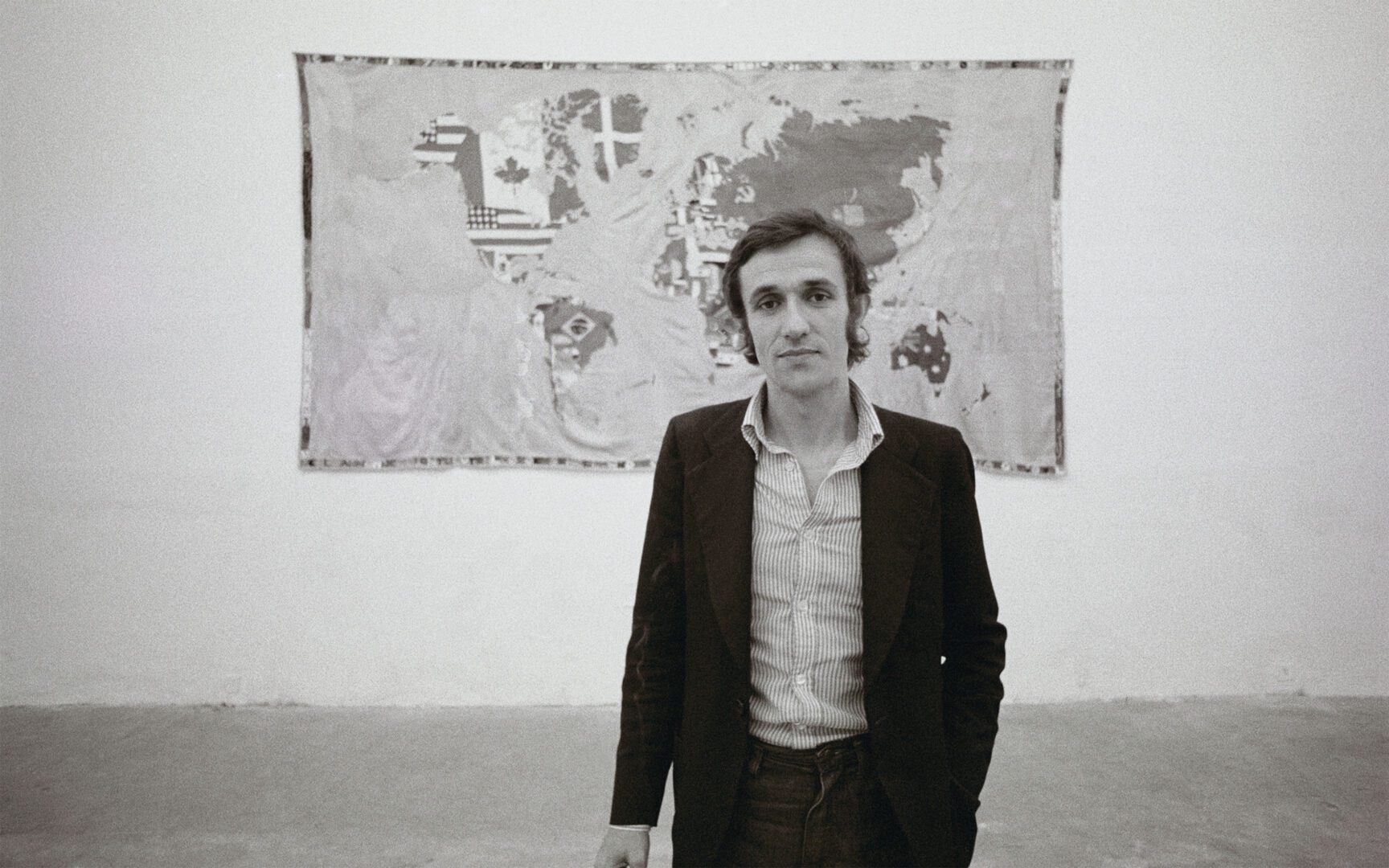

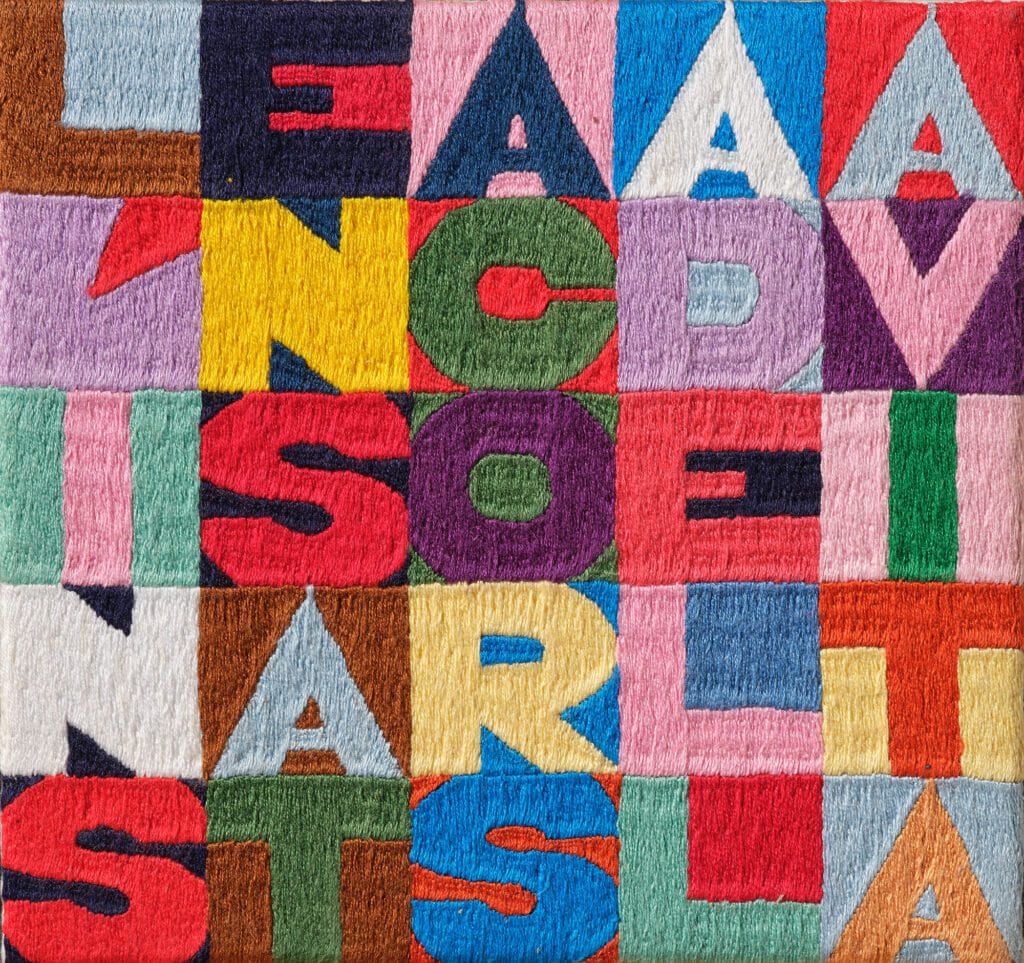

In the 1960s, a young Boetti became so enchanted by the sights and sounds of Kabul that he took up residence there. He particularly developed an appreciation for the traditional embroidered textiles of the region, which inspired some of his most iconic projects. From 1971 until his tragic death from brain cancer in 1994, Boetti embarked on a series of monumental pieces in partnership with Afghan embroiderers, first based in Kabul and then in refugee camps in Pakistan after the 1979 Soviet occupation. The war forced him to leave Afghanistan and made it impossible to oversee the projects himself, so he devised a system for sending the silk-screened fabrics from Rome to an antique shop in Peshawar. Several merchants he befriended would then distribute them to the refugee camps, and send the finished embroidered pieces back to Italy. Aside from country flags for Mappe (Maps), Boetti left all color choice to the Afghan women so that their traditional design sensibility would be on full display. He relished the fact that such details were given up to chance, and was enchanted by the results. In one example, rather than receiving swaths of blue stitches to represent the ocean, he was delighted to see that the water was represented in unexpected colors, like pink.

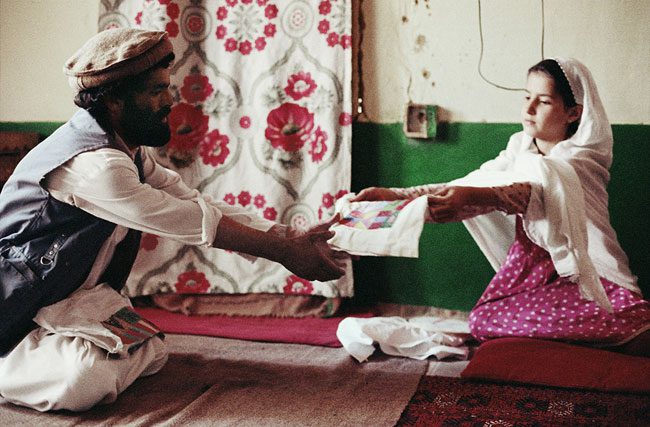

Boetti longed to see what it might look like inside the women’s rooms as they gave color and life to his pieces. Due to Islamic cultural traditions he wasn’t allowed to visit the embroiderers in their homes. Randi Malkin Steinberger, an American photographer and friend of the artist, made the trip to Peshawar in 1990 on Boetti’s behalf. That trip is the subject of this book. I had the pleasure of speaking with Randi some time ago, and she gave a thrilling account of traveling to one of the most dangerous places in the world for a project supposed to last two weeks but, due to an incident in the camp, lasted a single dizzying afternoon. As a woman, Randi was able to visit the women and left with candid portraits of them in their workrooms, embroidery hoops in hand, colorful boxes of thread scattered about, children at play. While the images in this photo essay are spectacular, they pose more questions than they answer. Did these women have a conception of the larger work they were contributing to? What did it mean to have this inclusive work in their larger context of displacement and isolation? Did they find dignity in the invitation to embroider in the tradition of their families at a time when fewer and fewer women engaged in such technical work? And did they ever see any of the money Boetti paid them for their work, which had to go through the men in the camps? While we can’t resolve these questions with any certainty, it’s important to wrestle with them. Boetti’s finished embroidery works are arresting and provocative, but they possess much more power when one trains the eye on the pieces of the whole, the toil and triumph behind the cloth.

This book provides a rare glance into the eyes of some Afghan women and girls nearly 35 years ago, mothers and daughters experiencing the trauma of war and displacement. Today, as we continue to receive news detailing the bleak realities of gender apartheid suffered by Afghan women and girls again under Taliban rule, we grieve for our Afghan sisters and want to raise awareness about ways to help. We encourage you to learn more about the vital efforts of the Afghan Women’s Fund.

DONATE TO THE AFGHAN WOMEN’S FUND

REFERENCED TEXT

Steinberger, Randi Malkin. Boetti by Afghan People. Santa Monica: RAM Publications, 2011.

FURTHER READING AT TATTER

Bennett, Christopher, Roy W. Hamilton, Alma Ruiz et al. Order and Disorder: Alighiero Boetti by Afghan Women. Christopher G. Bennett, Roy W. Hamilton, Alma Ruiz, et al. Los Angeles: Fowler Museum at UCLA, 2012.

Dupaigne, Bernard, and Francoise Cousin. Afghan Embroidery. Lahore: Ferozsons, 1993.

Hamidi, Rangina, and Mary Littrell. Embroidering Within Boundaries: Afghan Women Creating a Future. Loveland: Thrums Books, 2017.

Michaud, Roland, and Sabrina Michaud. Afghanistan: The Land that Was. New York : Harry N. Abrams, 2002.

Woven Witness: Afghan war rugs with the Afghan Freedom Quilt: Silenced voices of the Afghan Diaspora. San Jose: San Jose Museum of Quilts & Textiles, 2007.