My friend, Jacob, collects photographs of brooms. He says that the most valued criterion for a broom worth photographing is “is it leaning against a wall” and, usually, it is. He sees brooms everywhere, stacked together in groups––these guys look like a little family––or alone, not discarded, but also not in use. Jacob explained that brooms are easily anthropomorphized, in their posture, in their hairdos. The intrigue of brooms, for my friend, comes down to a kind of taxonomical analysis of their characters. They’re like us.

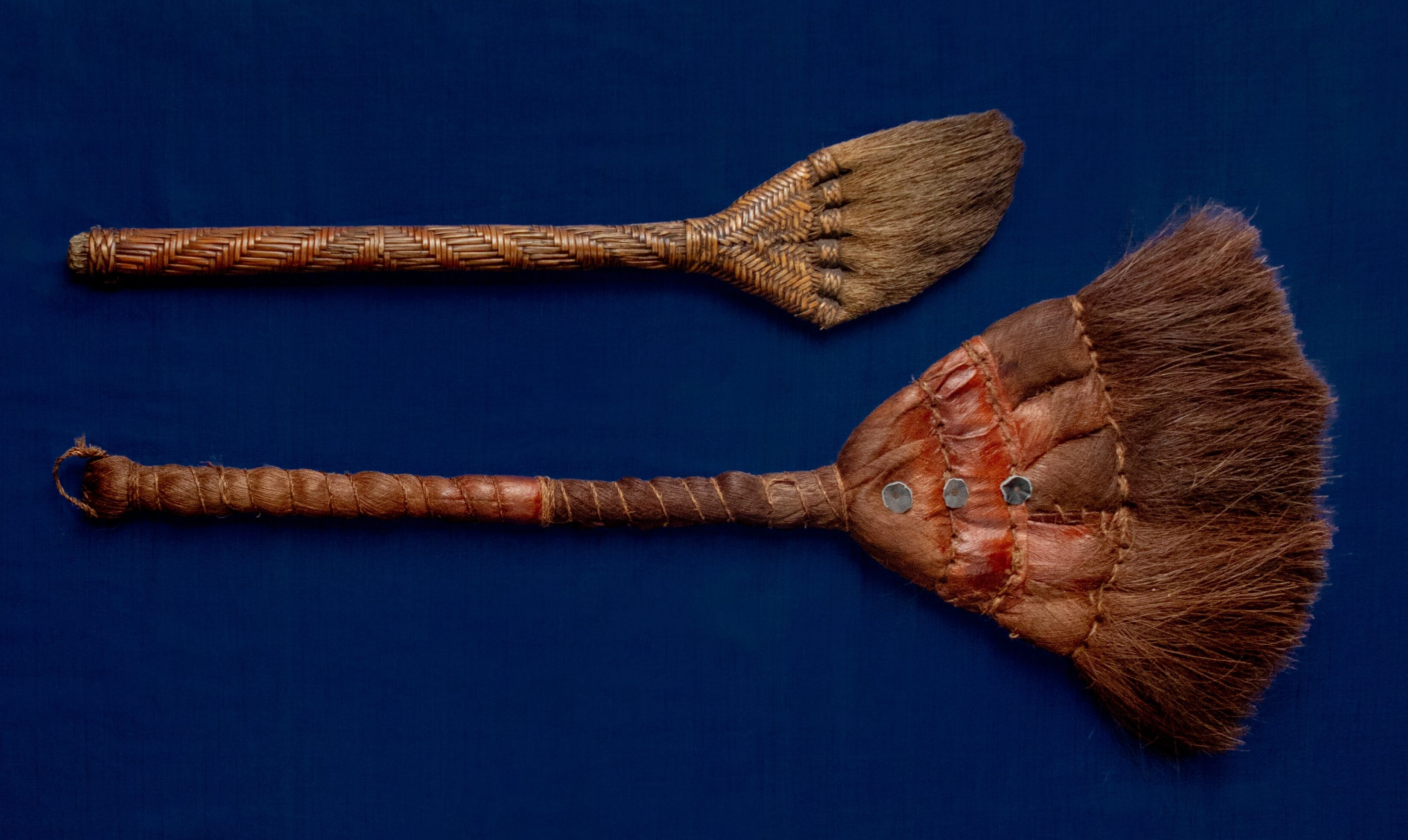

Brooms have been part of our lives forever, evolving with us. We’ve found evidence of prehistoric brooms made of bone and bird wings and burs and ivory. Indigenous communities in the Southwestern United States made brooms for cleaning pueblos from the yucca plant. In 2004, a small hand broom was discovered in the Nishi-Shindou ruins in Japan that dates back to the Tumulus (Kofun) period, around 300 AD. People in the Philippines used long coconut fronds to make handheld brooms. St. Lucia has a rich broommaking history, which begins with the ancient Latanyé broom––a handheld broom made from an indigenous palm of the same name. The broom inspired “the sweeping dance,” a kind of “entertainment exercise” that motivated people to complete their housework. The dance has been transmitted across generations, as has the craft of broommaking. We’ve found brooms in written documents, too; the 1541 Aztec manuscript Codex Mendoza––which offers descriptions of pre-conquest Aztec daily life––instructs girls to sweep the floors of their homes with brooms.

Brooms also have a spiritual, ritual or mythological significance in many cultures. In Japan, brooms actually originated not as household tools––broommaking didn’t become an official profession until the mid 1300’s––but as ritual articles. Brooms were brushed over the bellies of pregnant women to ensure safe delivery. They were used as charms intended to prevent guests from overstaying their welcome. They were used to brush evil spirits from a room. And there’s the myth of the Hahakigami, a spirit that takes up residence in brooms. The Hahakigami helps purify spaces, and on windy days in late autumn, might be seen dancing wildly around gardens sweeping up fallen leaves.

In Jainism, a pre-Buddhist Indian religion, all mendicants use brooms to sweep any living creatures, however small, from their path before they walk or sit to avoid killing them. The two sects of Jainism––Digambrara and Śvetāmbara––use different kinds of brooms: Digambaras use brooms made of peacock feathers that have been shed naturally; Śvetāmbaras make their brooms from long strands of white wool attached to a wooden handle.

In some ancient Chinese traditions, brooms are used to sweep the resting sites of ancestors in an act of continued filial duty, and as a way of honoring the deceased. (A tombstone from the Eastern Han Dynasty circa 25 -220 AD shows a man dressed in Hanfu, traditional Chinese dress, holding a broom). “Jumping the broom,” a tradition in which newlyweds jump over a broom during their wedding ceremony, was developed in enslaved African American communities as a symbol of the leap into domestic life. Legend has it that Dutch Admiral Maarten Tromp fastened a broom to the bow of his ship to indicate a “clean sweep”––a.k.a victory––in the 1652 Battle of Dungeness. The USS Wahoo also attached a broom to the periscope in February 1943 at Pearl Harbor; however, the ship was sunk mere months later by a Japanese aircraft.

The history of broommaking in America begins in the Appalachian mountains, where people made small hearth brooms to sweep away soot from their fires. These developed into besom brooms, which have a longer handle and a round broom head. In late autumn, small brush-like twigs and sticks, often from birch trees, were gathered and dried in a shed for two to three months. Sticks of hickory, ash, and oak were whittled into handles with one pointed end. A core was fashioned from the coarser twigs, while the more delicate twigs were assembled to form the outer layer of the broom. The broom head was fastened to the handle with twine or a strip of fabric.

But everything changed in 1797 when American farmer Levi Dickenson crafted the first round broom made from the sorghum plant as a gift for his wife. Sorghum, a cereal crop also known as broomcorn, grows long tassels––it looks like wheat, or rice, but it’s sturdier. Dickenson would strip the tassels from the plant, and bind them together along a wooden handle with thread or a strip of linen. His wife shared the broom with her friends and neighbors, and demand grew rapidly. In 1810, Dickenson invented the foot-treadle-broom machine, and soon he and his sons were mass producing sorghum brooms. The development of the treadle also helped Dickenson improve upon the design of the broom itself; by inserting split pegs into two holes drilled into the handle and wrapping the fronds around them, he was able to fasten the sorghum more permanently to the handle.

We owe the Shakers for the flatbroom we know today. In her book By Shaker Hands, June Sprigg writes that “the Shakers felt that work and worship were inseparable” (Sprigg, 12). Cleaning, cooking, building––any form of labor, really––were almost like a ritual act of prayer for the Shakers. And so the tools they used in their labor were ritual articles as much as they were practical objects in the household. The invention of the flatbroom followed in a long tradition of simple improvements to otherwise inconspicuous household items (the Shakers also developed a better clothespin, better drawers, swivel foot chairs, the circular saw, and seeds sold in packages).

Brother Theodore Bates of the Watervliet, New York Shakers “saw the Sisters sweeping in 1797 with their common round brooms and realized they were wasting time and effort. He didn’t offer to help sweep,” Sprigg writes, “but he did flatten the brooms to make them more efficient” (Sprigg, 12). In 1798, Bates invented a wooden broom vise, which fanned and clamped sorghum tassels together. This allowed him to thread through the corn with heavy twine, rather than merely lashing it to the handle. The result was a flat broom that was not only sturdier, but covered more ground. Watervliet became the first Shaker community to grow broomcorn, and Bates’ design––as well as the crop––spread across New England and the east coast. Broommaking became an important facet of Shaker culture, and the brooms were respected and cared for. The Shakers would hang the brooms on their walls when they were not in use, and would clean them, sometimes even covering them with cotton hoods to protect the fiber. Bates shared the vise and the new design with the world outside the east coast Shaker communities. By 1850, more than a million brooms were made annually in Massachusetts alone, and were exported as far as South America.

Although synthetic brooms are overtaking today’s market, many artisans still use the Shaker model, as well as other traditional broommaking techniques. If you’d like to become a part of this long tradition, please join us at TATTER on October 30th for a broommaking workshop with artist Cynthia Main. Students will learn to make traditional American hand brooms and delve into the rich heritage of the craft.

REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING

Deo, Shantaram Bhalchandra. History of Jaina Monachism from Inscriptions and Literature. Poona: Deccan College Postgraduate and Research Institute, 1956.

Hart, Jeffrey. “Besom Brooms with Jeffrey Hart” Nettlecombe Craft School, July 2025

Hildburgh, W. L. “Some Magical Applications of Brooms in Japan.” Folklore 30, no. 3 (1919): 169-207.

Hobbs, Karen. Swept Away: The Vanishing Art of Broommaking. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, 2017.

Komanecky, Michael K., ed. The Shakers: from Mount Lebanon to the World. New York: Skira Rizzoli, 2014.

Meyer, Matthew. “A-Yokai-A-Day: Hahakigami.” Matthewmeyer.net (blog), October 11, 2013.

Roy, Ashim Kumar. A History of the Jainas. New Delhi: Gitanjali Publishing House, 1984.

Sprigg, June. By Shaker Hands. New York: Knopf, 1975.

Stephenson, Sue H. Basketry of the Appalachian Mountains. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1977.

“Wa-bouki: Shaping Japan’s Cleaning Culture.” Hasegawa Eiga (blog). November 17, 2022.

Edie Wolfe Lipsey is from Brooklyn, NY. She’s an undergraduate at Yale University, where she is a double major in Studio Art and Humanities with a concentration in Modernist Literature. Edie joined TATTER in summer 2025 as a Library Intern.