Ikat is an ancient textile tradition, a form of weaving patterns directly into cloth. Rather than dyeing the cloth after weaving, ikat weavers resist dye the threads before they put them on the loom. With practiced hands and skills that seem almost magical to observers, the variegated thread layers to create intricate patterns. While some weavers dye the warp threads and others the weft, double ikat— patterns made through dyeing both the warp and the weft— yields the most complex result.

Silk weavers in Gujarat, India, have practiced the art of double ikat for centuries. For many families, the knowledge is inherited from generations of practice. For these weavers, cloth is a major player in socio-cultural and economic exchange. Earlier this year, Dr. Urmila Mohan visited the state of Gujarat in India and traveled to major ikat handweaving regions as preparation for longer fieldwork. On Thursday, July 11th, she will presenting a virtual lecture through Tatter on the history of Gujarati silk ikat, its cultural heritage, and the role it plays in the modern marketplace. She will also discuss how the craft’s expansion and democratization in recent decades has created socio-cultural change in the lives of weavers themselves.

In advance of her lecture, we sat down with Dr. Mohan to discuss her research and relationships with weaving communities.

Before we start the interview, I just wanted to say how excited I am for your talk. I know very little about ikat, though I find it incredibly interesting. It seems like such a magical process.

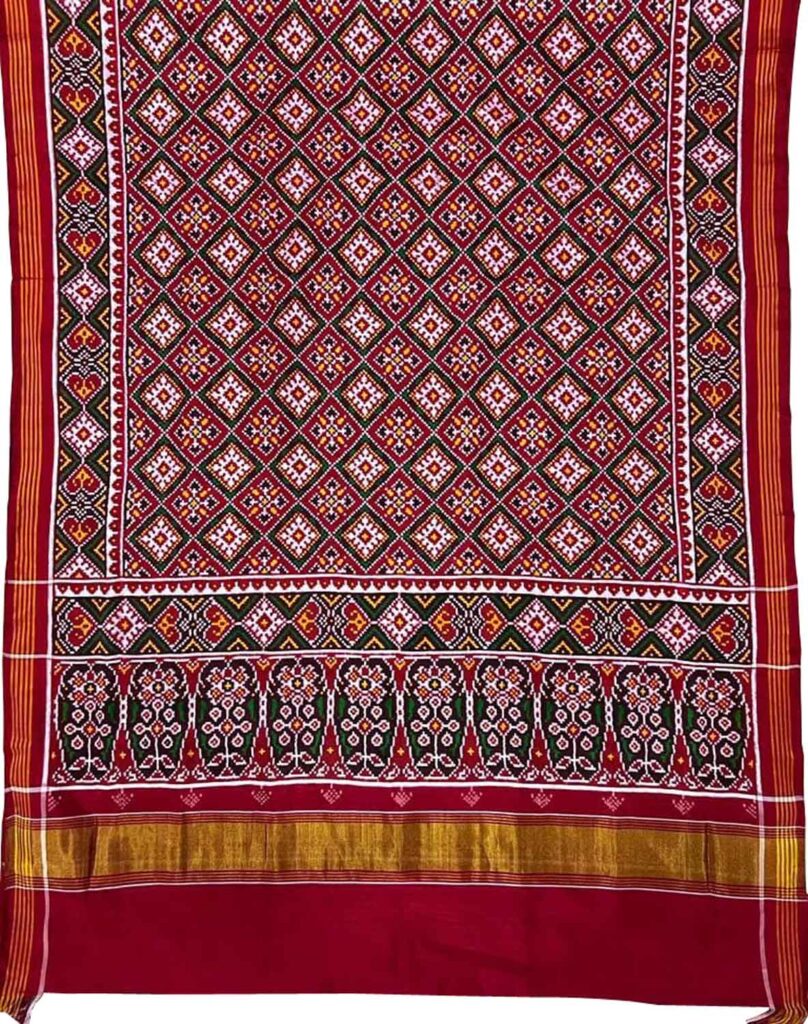

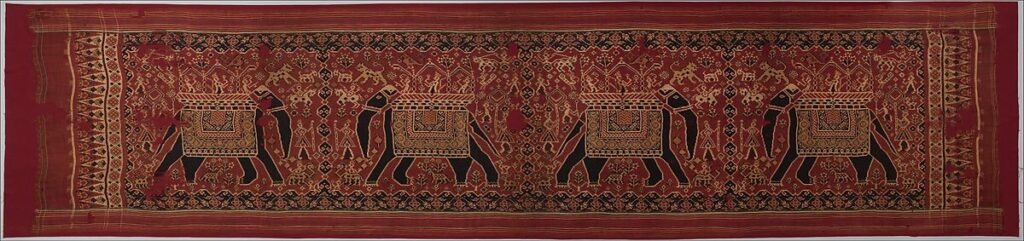

I think that the fascination is a big draw to ikat. I love when I get to actually show the textile to people and say, okay, look at it closely. It’s not a print. It’s not a process where the warp was painted. It’s dyed like that before it reaches the loom. People might use words like artisanal or heritage, and I think these are all just ways to say that it comes from millenia of innovation, practice, and tradition. There are records of a cloth called patola from across South and Southeast Asia dating back to 700-800 CE. Is that the same method that we see today in Gujarat? I don’t know. But the larger pieces in museums or private collections and that are double ikat from Gujarat are maybe 200 years old.

I think that this speaks to our fascination not just with the technique but with the fragility of cloth. It is not a medium like stone or metal. It can do all these things that those other materials cannot, and it is of course very close to our bodies. Especially in today’s world, people are fascinated that somebody would invest this much labor, this much time, these many resources into making something like ikat cloth, and especially double ikat where both the warp and weft is tied and dyed before weaving. Historically, there was a belief that this cloth has certain talismanic powers both in India and South East Asia. It might be put in a baby’s cradle, or used to clothe a deity. I’m not sure that the connection to spiritual or transcendental power is there as much today and if it is perhaps it’s being created through recursivity and new linkages. But I think there are remnants of it in the technique and its cognitive effects, and it draws people in.

“Especially in today’s world, people are fascinated that somebody would invest this much labor, this much time, these many resources into making something like ikat cloth, and especially double ikat where both the warp and weft is tied and dyed before weaving.”

In terms of the talismanic power, does that come from the time that’s invested in the cloth?

You know, that’s a wonderful question. I think that is part of it. When we speak about power, it could come from so many things converging, transforming and overlapping. Silk double ikat in Gujarat was a weaving form that originated because of royal patronage. It wasn’t just a luxury textile, it was associated with the court. It was associated with people who are themselves considered to be descendants of a spiritual lineage that is connected to cosmology and deity. Do people think about all those things when they attribute a certain feeling or a power to it? I don’t know. But I think it’s a convergence of all these things. It’s both this enchantment of technology that you’re talking about, the wondering how someone could make this thing, and it’s also the cultural memory of the royal and religious associations of the cloth.

As someone who can’t do it myself, there’s something very magical about the idea that a weaver can just intuitively know where to dye up a length of thread so that it will come together to create a predetermined pattern many, many steps down the line. It absolutely makes sense that it would imbue the cloth with some sort of power. It’s also hard to imagine someone doing that without the assistance of something greater than just the human mind. But I think also part of the association with divine intervention probably allows us to discount the weaver and the dyer. Instead of ascribing this incredible skill to a person who maybe we don’t think of as being an intellectual person, or a high status person, we implicitly suggest that there’s no way they could have done this without some sort of divine assistance.

You really put your finger on something. I think that is the tension. And I think that tension gets amplified in a contemporary scenario when that knowledge has been– let’s use the word ‘democratized’. What I mean is when the knowledge that was previously contained by caste boundaries goes outside. This used to be hereditary knowledge. You are supporting yourself and your family and your future by making sure that knowledge stays with your family, the knowledge of the dyeing and weaving techniques, the knowledge of the patterns, your contacts with who was buying that fabric from you. A lot of these were private commissions. People were not buying in shops, you would actually have connections either through a trader or a family. Even in the early to mid 20th century people would come from Bombay and other parts of India to the weavers because there was no large regional or national distribution system of these textiles. And they certainly were never made on that scale that there could be one. That is something that only happened over the past few decades.

“It’s also hard to imagine someone doing that without the assistance of something greater than just the human mind. But I think also part of the association with divine intervention probably allows us to discount the weaver and the dyer.”

Let’s not forget that these weaving techniques were not innovated to make scarves and handkerchiefs. They started within a South Asian and Southeast Asian wider culture of wrapping fabric. We have to understand the technique of how these fabrics are worn if we want to understand why they were made and why the patterns were made a certain way. I think this is also a sticky point when you come from a culture where everything is cut and sewn. You tend to be unaware of the knowledge that is contained in draping and wearing a fabric a certain way. If you’re wearing a Gujarati style sari it is very, very different from wearing it in a Nivi style, which we think of as the pan-Indian sari style. Draping knowledge and history is involved. People don’t talk as much about that as they should. And also a very, very important distinction is how the fabric feels. The double ikat silk patola that you see in that photograph in the ad for my talk. I was touching it and could ‘feel’ the sheen; it actually felt quite fine but I was appreciating it through many senses. You can see it’s actually a double ikat, it’s a weft and warp-dyed pattern. What is different now is that in the interest of producing this quicker, it’s often just the weft that’s dyed.

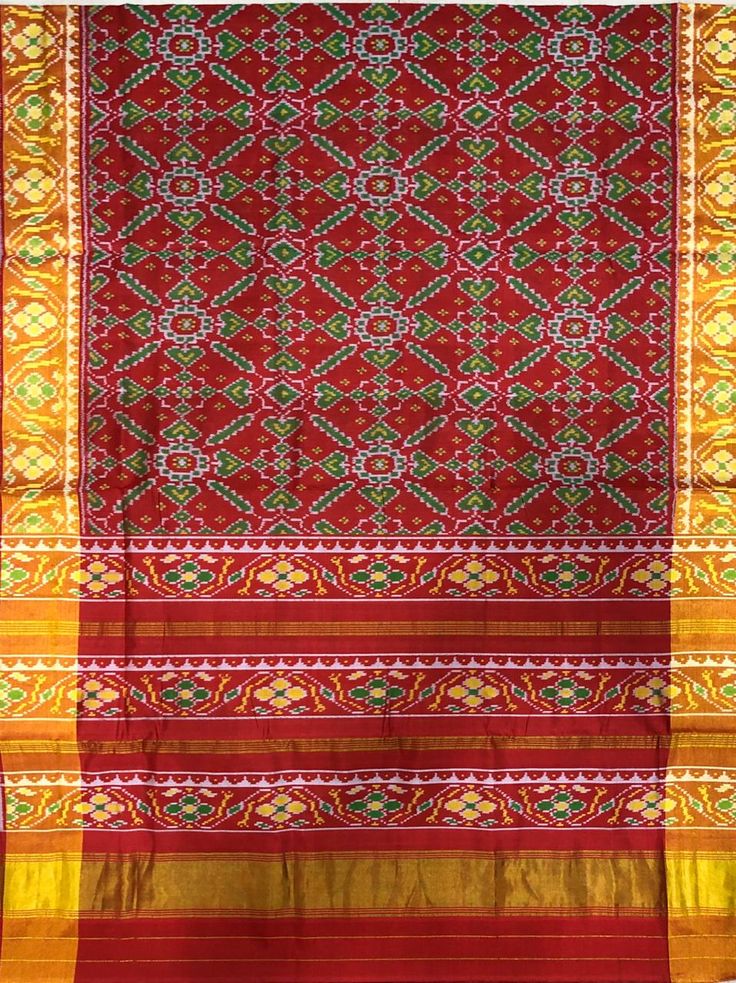

So we are talking about this moment in post independence India when this double ikat knowledge kind of escaped. It made its way into a different community, a different network. Because it was so labor intensive, and you’re not able to make as many saris, and you’re not able to get back your investment or get paid as quickly with double ikat, they moved to doing weft or single ikat.

Where you just dye the threads as they go horizontally?

Correct. Which is also an incredible skill, but much less intensive and also allows for much less interesting patterns. There’s something interesting happening here, which I think also speaks to that tension you were talking about, which is what happens in this democratization process and boundaries shift. People begin to lose the concept of the cloth as spiritually important. Of course it still has a connection with the traditional, it has a connection with the ceremonial, so people will wear it for weddings or for certain occasions. But increasingly, what is happening is people are buying it just to be able to wear it to those occasions. So it’s not contained to that traditional context of wielding or embodying spiritual power. We’re at the point where we’re seeing these different channels and pathways emerge for this particular form, to the point that it’s actually a thriving industry. It becomes more about fashion as a socio-economic phenomenon than invoking the presence of divinity through auspiciousness or talismanic power. But I hope to be proven wrong when I actually do the research.

It’s so interesting, because of course the more accessible it becomes, the less precious it is.

That’s absolutely right. And it’s no longer a skilled process of just one producer’s family. Or even one cluster of families. What we see happening here is you have some players in this terrain who are the original caste community of double ikat producers. They are called the Salvis, because there was one particular community in Gujarat who were designated weavers of double ikat patola through royal mandate and whose last name was Salvi. The community in general made these cloths for hundreds of years but in the 20th century many of them just moved away and took up other occupations, until it came down to about three or four families. So, even today, if they were making the cloth or it was made under their name, the value of that would be higher as compared to somebody whose name is something else, because they don’t come from that tradition and cannot claim that brand. So when the field is opened up what we have here is very much a contemporary contestation of value.

It absolutely makes sense that today, if you want your children to be successful, you don’t want them to be textile makers. It’s such an enormous loss of inherited knowledge, but also it makes complete sense within a globalizing culture that doesn’t value textile work. Historically, would you have had children being part of the making process, doing simpler tasks through childhood and then being trusted more and more with the skilled aspects of it as they get older?

Yes, I think that the learning very much just happened as a part of daily life. Even if the child went to school, they would come back and sit with the parents as they worked. I’ve heard this happening even with families weaving weft ikat in Gujarat that don’t come from the “traditional” validated community. I also want to say that a number of people who started making single and double ikat after it was more democratized came from weaving families themselves. They were just weaving a much lower status, less expensive hand spun cotton fabric, called khadi, and the status of this cloth was ambivalent. On one hand it was elevated by Gandhi as a symbol of the Indian independence struggle from the British but on the other hand it was considered as common. So there’s a tension there. I’ve actually heard people say things like “how could they [the weavers who moved from cotton to silk] possibly be able to do that?” Of course when you have sufficient economic motivation and you have the skill and somebody to learn from you can do it!

That also makes sense, though, in a culture that has a history of rigidity within castes, that you would also have a push back against someone you perceive as being lesser, creating something of high status. There would be an understanding that cloth becomes less precious if it’s woven by someone who’s less important. Of course, that’s not just India. When you see someone with a fine arts degree making fabric and making clothing in the United States, it’s valued much more than what’s made by someone who is of equal skill, but is of much lower status.

You’re absolutely right. I was speaking with an indigenous Moana Oceania artist and curator, and she said that’s why the word art is important: performing arts, weaving arts. It’s all art. In India there is just one word kala that is used for art, craft and design. There’s an endless debate that Western academics and especially colonial scholars have had for more than a hundred years about fine art, folk art, and craft. And now design. A lot of these boundaries really are irrelevant to the people that I’m dealing with.

It’s very much a created binary. And the sad part is, of course, we can’t completely ignore it because there is so much institutionalized power in those terms. In order to have something be taken seriously, it has to access that power. So it doesn’t make sense to completely cut it off from that. But then, it’s that question of who gets lost in that process?

That’s exactly it. When we have this object, which is the one physical object, but it is being perceived and turned into something else by somebody who’s in the heritage space, turned into something else by somebody who is in the Salvi family and market or turned into something else by somebody who’s in the development industry. It’s the same object, but it becomes something else because a different set of values are being attached.

At the same time, it also makes sense that a craft is worth something different when it’s made by someone whose ancestors have been making it for centuries. There is something very spiritual and magical and rooted and connected when someone is doing something their ancestors have been doing for centuries. This is one of my favorite types of lectures that we get to host at Tatter, because it’s just something so complicated. There’s no objective answer. It’s all of these truths at once.

I enjoy the complexity. It can be very emotional, when you’re in the field, and it can be very frustrating. We should remember that I’m not doing archival work. I’m actually going to these places, and I’m actually meeting these people. And the way that they are responding to me is as a person of Indian origin who can speak Hindi and who is learning Gujarati (shout out to my amazing Gujarati teacher!), but is not living in India and is coming with certain resources and perspective. Sometimes I will be speaking with an artisan and they’ll say something like “we are not as highly educated as you are, let my son talk to you.” Or, you know, “My sons can speak better English.” In some cases, it’s more of a confrontational type of dialogue, which is also very good. I think it’s important for an ethnographer to deal with these things. It causes me to question what the value is of having an ethnographer or anybody going and doing the research in the field. You’re making yourself vulnerable. You’re meeting people repeatedly. It’s not like you’re coming in, interviewing them once or twice, and then leaving. You’re trying to form a relationship with them. And that is the risk that someone like me takes. There’s been so much flack about anthropologists and ethnographers. We tend to forget that it also depends on who is doing it. Our positionality, our ability to communicate and be worthy of the trust and the time people give us.

People talk about craft, and people talk about community. But the question for me is, how does one become the other. How does one individual or group actually come together? How do those relationships get formed? How do they end? How do they transform, how do they become something else? And I think that all speaks to these assemblages of power, whether we are trying to harness the power consciously or whether we are trying to study it. I’m very excited by that process.

There is this disconnect, where academics and curators discuss craft or weaving as something that happened in the past. I want to look at who’s doing it now, and make a responsible account as well as understand and depict the makers as humans. I am not an activist but this is how I use research and education on my platform The Jugaad Project to raise questions and uplift all of us through understanding. I think that’s a really important thing to make clear. It’s not just historical. It’s a living practice and we are all part of it.

FURTHER READING AT TATTER (WITH NOTES FROM DR. MOHAN)

Patolas and resist-dyed fabrics of India by Mrinalini Sarabhai (call number NK8876.S27)

Ikat textiles of India by Chelna Desai (call number NK9504.7.D47)

These books offer an introductory, concise overview of Indian ikats. This is useful for readers who wish to acquaint themselves with Indian textiles.

Indian ikat textiles by Rosemary Crill (call number NK9504.7.C75)

An overview of rare and varied Indian ikats from the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

Patola of Gujarat: Double ikat in India by Alfred Buhler and Eberhard Fischer (call number NK9504.7.B78)

Co-authored by ethnologists, this two-volume set remains the most substantive study of silk double-ikat called Patola, made in Patan, Gujarat. It covers the Salvi weaver community as well as different Patola uses and types.

OUR LECTURER

Urmila Mohan (Ph.D., 2015, University College London/UCL) is a public-facing anthropologist of material culture and making with a focus on cloth, clothing, and bodily practices. She is Honorary Research Fellow, Dept. Of Anthropology, UCL, and the founder/editor of the open-access digital journal “The Jugaad Project” on embodiment and belief. Dr. Mohan has published and lectured extensively on materiality, embodiment, and aesthetics in contexts of museums, religious communities, and pandemic maker groups in India, Indonesia, and the U.S. She curated the 2018 exhibit and authored the monograph “Fabricating Power with Balinese Textiles”. She will be undertaking long-term research on ikat in Gujarat, India (2024-2025) as a Fulbright-Nehru Academic & Professional Excellence Awardee. A transdisciplinary scholar who works across domains and geographies, she draws upon her background in anthropology, design, and art to develop and connect these fields through the study of materiality and embodiment.