On the Lunar New Year, whether I am back in my hometown in Taiwan, or celebrating in Manhattan’s Chinatown, I always seek out the Dragon Dance. The enormous dragon weaves down the street, chasing the dragon pearl ahead, dancing to the beat of the dragon drums. Its fabric covered body ripples in the air, revealing glances of its bamboo understructure through the sun.

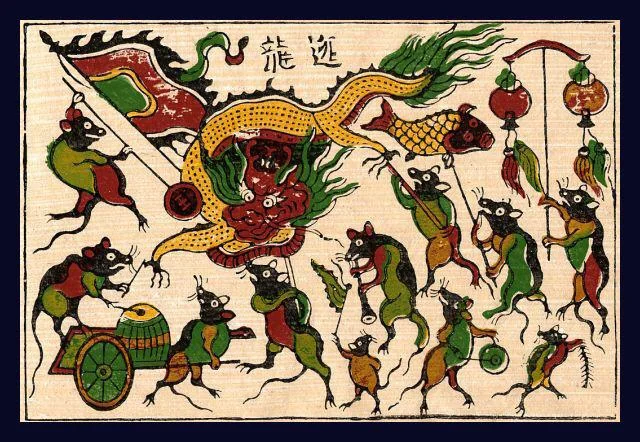

In Chinese folklore, dragons were kind and powerful creatures that dwelled in the water and controlled the rain. The dragon dances were recorded in the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) as a ritual to wish for prosperous harvests and evolved over time into a tradition to ward off evil spirits and wish for good fortune.

From ten foot long puppets for children to a thousand foot long dragon lifted off the ground by an entire crew, the dragon dance has been developed for over two thousand years and has evolved into vastly different styles across Asia. Every move has earned a poetic name, every color carries a special meaning. The puppets can be made with woven straws, pasted paper, and even wooden stools, but the most familiar kind is built from bamboo strips tied together and covered in cloth.

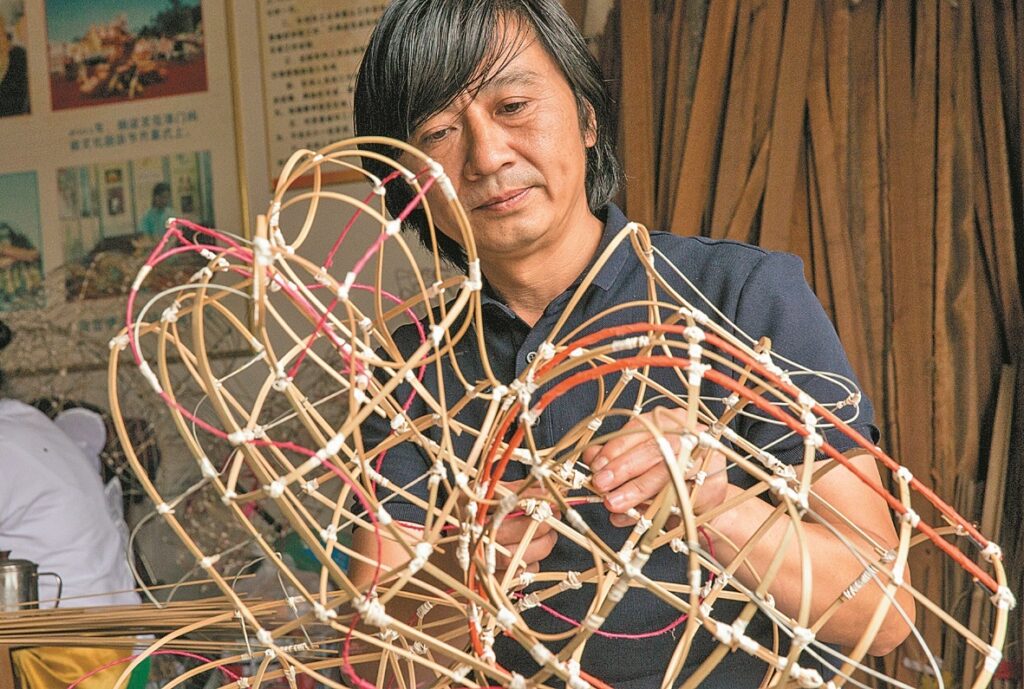

Puppet makers split young bamboo shoots into thin strips and tied them together with wire into the head, the tail, and sections of the body. The head, with its articulated jaw, is meticulously constructed by experienced artists to capture the high spirit of the mythical beast while the tail and sections of the body are made with perfect symmetry to balance on the control poles. Fabric is sewn together and glued to the bamboo frames, clothing the skeleton. The addition of embellishments such as trimmings and furs gives each dragon a unique character.

The craft of building these puppets has evolved swiftly over the course of the last century. While dragon scales used to be hand painted onto the fabric, digital printings have replaced much of the laborious process. Some dragons even choose luminous fabric to glow in blacklight and swapped bamboo frames for plastic ones to lighten the weight on the dancers. All these innovations have helped to transform the traditional dance into a spectacular performance in recent years.

Artists dedicated to building the puppets strive to keep the tradition alive and pass their skills down to the next generations. Many of them are also passionate about participating in performances, coaching dance teams, and improving their craft in the process. One of the artists proudly stated that he would not count the order complete until he had shown the customers how to dance with the dragon and get the crowd cheering for the arrival of a new year.

REFERENCES

Cai, Zongxin. “舞龍之淵源與發展.” 台灣傳統雜技藝術研討會, edited by Tengda Wu, Teachers College National Taitung University, Mar 1999, p. 69-90.

Lee, Meiyu. “Dragon Dance.” National Library Board: Singapore, Jan, 2016, www.nlb.gov.sg.

Long, Dechun and Xie, Feng. “非遗点亮生活 铜梁龙灯彩扎见功夫.” Chongqing Broadcasting Group, Nov. 2021, www.cbg.cn.

Lu, Shaojun. Research on the Dragon Dance Custom. Science Press, 2020.

Wang, Jinqiang. “奉化飞出一条龙.” People’s Daily Overseas Edition, June 2018, www.paper.people.com.cn.

龙飞“奉”舞: 国家非遗奉化布龙数字文创生态坊. www.sportsichlab.org.