In November 1969, the Greely Tribune in Greely, Colorado published an article titled “Space Age Finds A Use for Old Skill.” The delicate gold-plated mesh antenna that had recently beamed the first steps on the moon by astronaut Neil Armstrong would never have been able to send the signal 250,000 miles back to earth without the aid of a woman whose specialization was not in space technology, but rather in couture sewing techniques. When the antenna was damaged shortly before its Apollo 11 launch, the unnamed reweaver was brought in to painstakingly rethread the broken pieces of mesh. To this day, this process cannot be replicated by machine.

The practice of reweaving small holes in woven garments by pulling threads or cutting small swatches of fabric from the hems in order to invisibly repair the damaged fabric has become a highly specialized and dying art. Today, few people mend their textiles. Both the skills and the needs have begun to vanish as the fashion industry constantly churns out new styles. People tend to discard their damaged clothing in favor of new and relatively cheap garments, and in most cases mending is an anomaly rather than the norm. Visible mending has been around for likely as long as we have had clothes to tear— it’s less expensive, time intensive, and easier— but in the modern era of spending rather than mending, it has become something of a revolution. People display their skill, creativity, and scrappiness by patching, embroidering, and stitching over worn garments. After all, if you are taking the time to repair your clothing in 2025, why not show off your work?

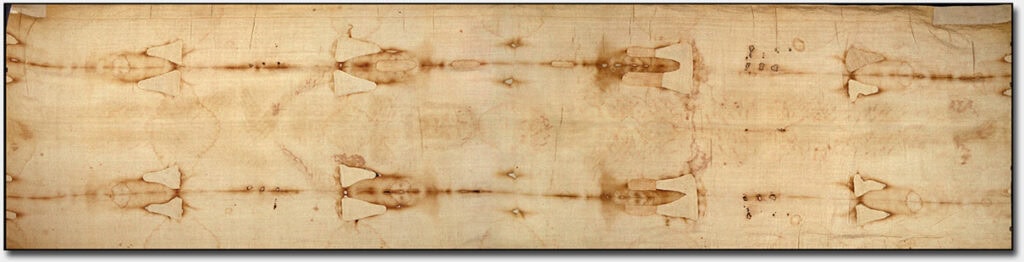

Still, reweaving holds an almost magical allure. It promises what few other mending techniques can: your beloved garment returned to its original shape, perfectly and seamlessly repaired. Reweaving is an ancient practice, practiced worldwide to restore time intensive and costly textiles from the inevitable wears and tears of daily life. In medieval and early modern England, tapestries could easily cost more than the grand estate where they were hung. Tapestry reweavers were required to complete a seven year long apprenticeship in order to take up the profession. Other extant examples of ancient reweaving show the spiritual rather than monetary value of their textiles. One of the most studied pre-modern examples of reweaving is stitched into the fabric of the Shroud of Turin. Allegedly stolen during the Sack of Constantinople in 1209 CE, the shroud is a length of linen imprinted with the full size image of a tall, bearded man believed to be Jesus Christ. As the story goes, this simple fabric was wrapped around Christ’s body after the crucifixion; the authenticity of the shroud was disputed as soon as it emerged for the first time in recorded history in France in 1354 CE. Radiocarbon dating in the 1980s agreed with skeptics that the shroud was made no earlier than 1260 CE. Several scholars disagreed with this finding, arguing that the shroud was so frequently mended over the centuries by invisible reweavers that the portion tested was a medieval reweaving rather than part of the original first century shroud. While this remains a minority position among textile scholars, it is widely accepted that the shroud has been both patched and rewoven over the centuries. The care and time invested in its survival are what allow us to study it today.

Reweaving first piqued my interest in the summer of 2024 when, while searching through the TATTER library stacks, I happened across two spiral bound correspondence course books: Invisible Reweaving by the Fabricon Method and The Frenway System of French Reweaving. They were produced by the Fabricon Reweaver Company, copywritten in 1951 under the names of William Bogolub (1915-2001) and Fannie Holleb Bogolub (1881-1985). A mother and son from Chicago, the Bogolubs wrote and printed several correspondence courses for garment and upholstery repair, teaching multiple forms of patching and reweaving from the early 1950s through the late 1990s. Their popularity extended beyond the US, and they even partnered with other technical correspondence colleges such as Stotts in Australia to reduce the expense of international shipping. Instead of a seven year apprenticeship, students could learn to reweave and operate a business from the comfort of their own home.

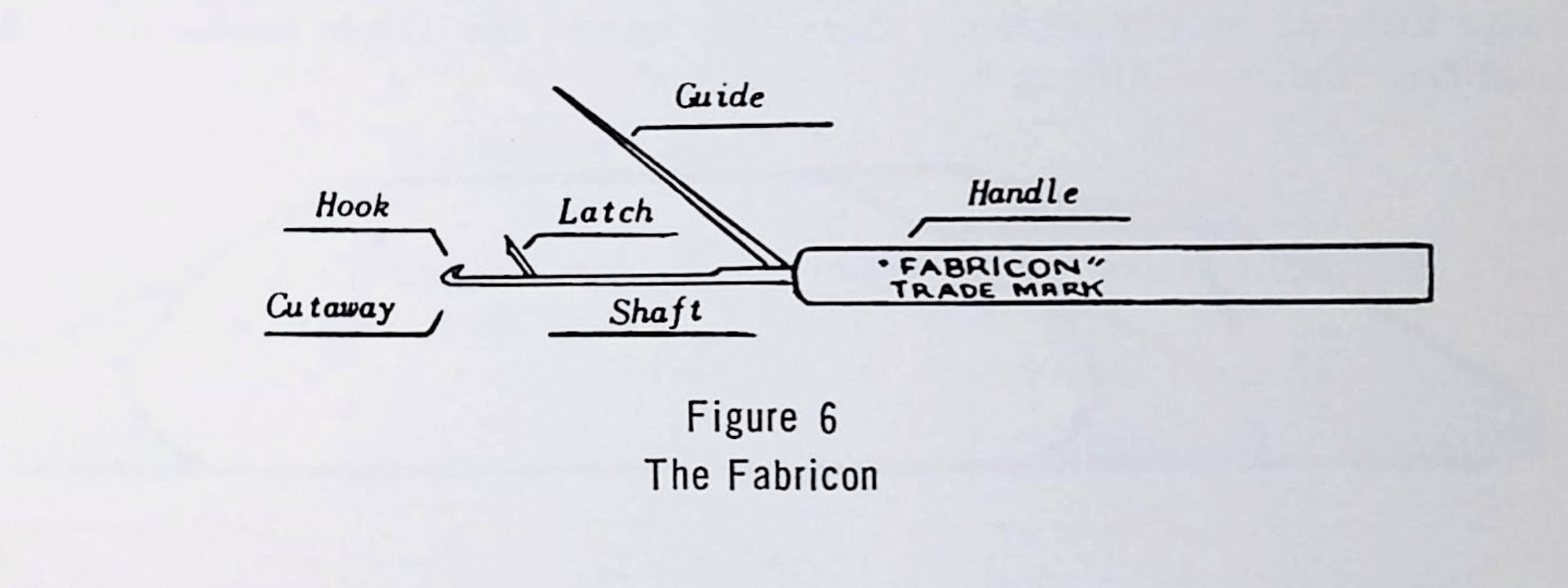

While several reweaving correspondence courses existed at the time, one thing made Fabricon stand out: the Reweaver. Though ostensibly simple, this tool is relatively unique and very difficult to find today. Intrigued by the diagram in the correspondence course, I first came across an image of the tool itself published on the Internet forum, Collectors Weekly, from 2010. The poster had come across it, thinking it was a seam ripper, and was trying to figure out its use. User “dolyco” responded: “My husband paid for the Fabricon Reweaving Course in the 1990s. It came as a kit with the Fabricon reweaver and the French Reweaving method. I really like it and I cannot see it as a scam if it came with instructions and I learned how to use it.”

If the word scam piques your curiosity, it certainly did mine. A search through Federal Trade Commission archives led me to a 1955 complaint which alleged that Fabricon made false claims about how simple the process of reweaving was and how much money a Fabricon reweaver could make. If you have the physical dexterity, social connections, and basic knowledge of hand skills, the course provides an excellent step-by-step guide to invisibly reweave small holes in woven fabrics and make money to supplement your income by doing so. But the course’s claim—that any person can learn the skill, fix textiles impossibly quickly, and make enough money to support themselves—is demonstrably false. While some of the language within the course was scaled back, recommending that students start small and work out of their homes rather than investing in expensive tools or a storefront, little changed in their public claims. In 1961, a Fabricon advertisement in the Virginia Chronicle promised that students would be able to make $240-$300 a month ($2600 today) “all profit” if they only took on two pieces per day. In 1989, Fred Sark of Fabricon estimated that “90% of the reweavers trained in this country learned their craft from Fabricon” and boasted that demand for reweavers was continually increasing as the skill was becoming rarer. It’s a compelling promise, especially for the stay-at-home mothers and financially dependent housewives who made up the majority of their business. But at $70 ($750 today) in upfront cost, it was no wonder that a 1955 article in the Miami News referred to Fabricon as a “mail order racket” taking advantage of “simple honest citizens who happen to believe that others are honest.”

Having both dexterity and knowledge of hand skills, I was curious to discover if I could use the course to teach myself to reweave. While French reweaving is generally done using a needle, I figured that my best bet for achieving the technique at speed would be to use the tool that originally came with the kit. When I spoke with Toni Columbo, an invisible reweaver based out of Boston who never took the course herself, she confirmed both that she uses the tool and that they are incredibly rare. I set a Google alert in 2024, hoping to secure one for myself the next time one did pop up and began slowly collecting anything the alert turned up: my own copy of the course books, a set of needles and samples from the original kit, a tiny Fabricon reweaver badge about the size of my thumbnail, and even a “Magni-Focuser” which was often advertised alongside the course as a useful tool of the trade.

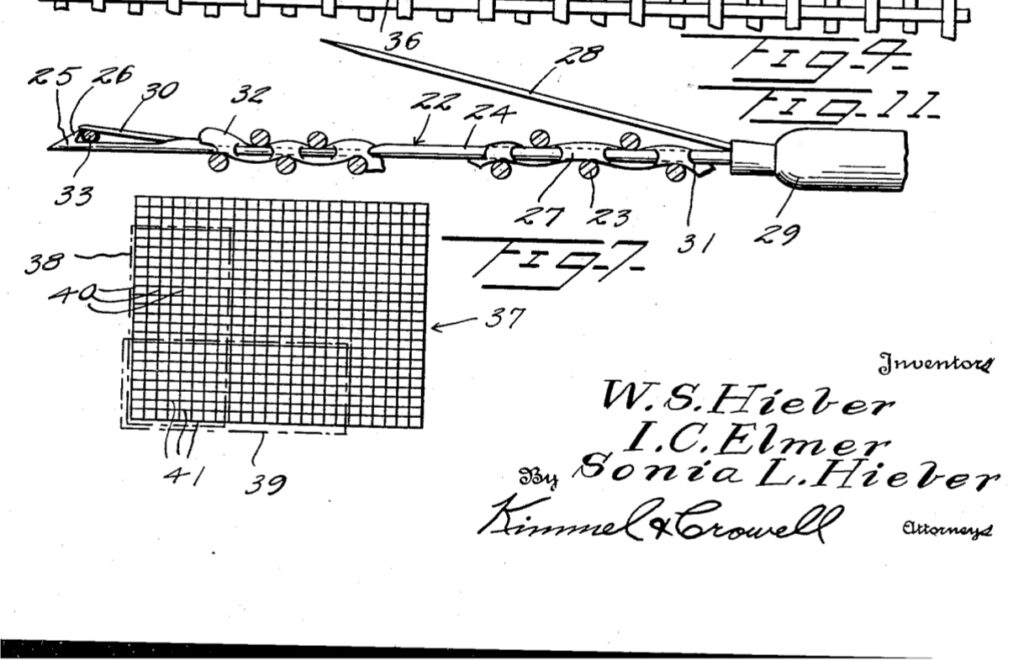

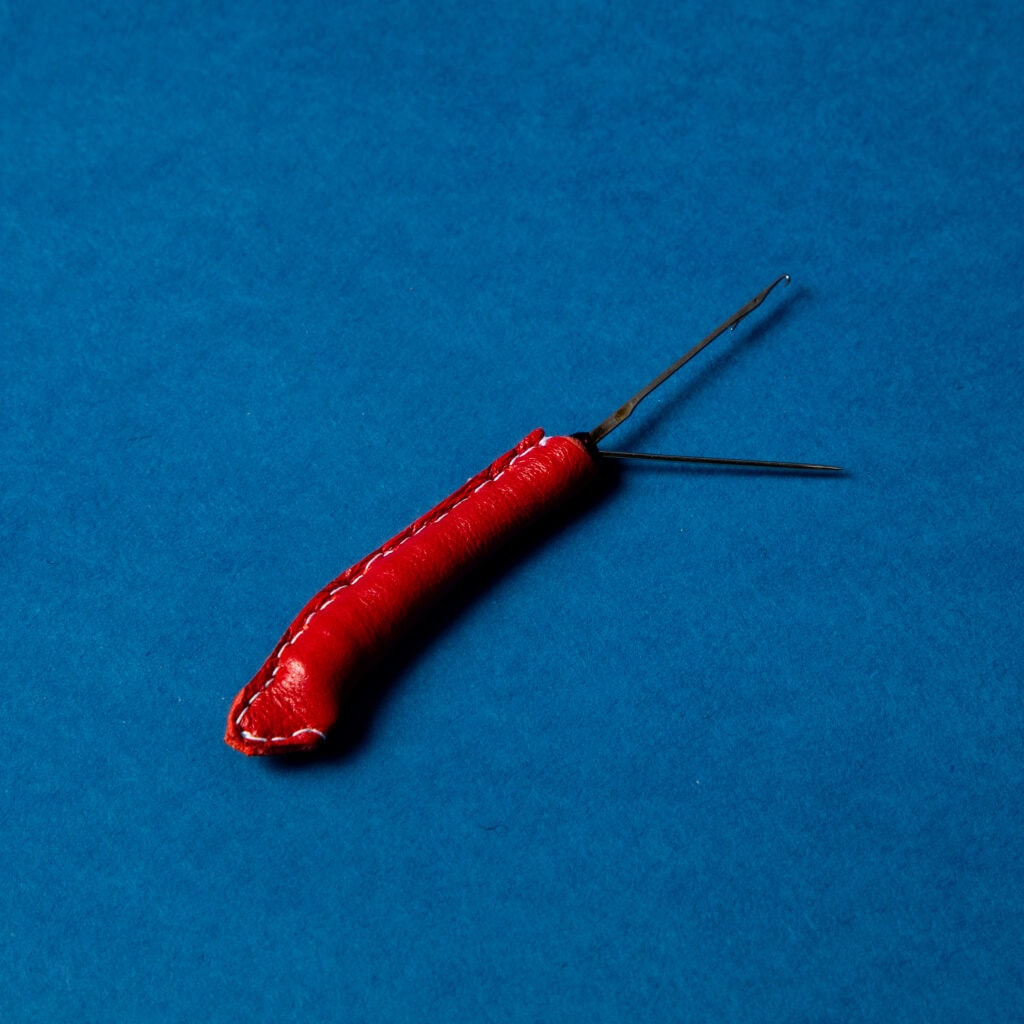

It was almost a year later when three reweaving tools all emerged within the span of a few weeks. Unfortunately, my desire to test out the mechanism did not quite justify the $100-$130 purchase, and I ultimately decided to make one myself. Armed with the component parts—a tiny latch hook (made for mending runs in nylon stockings) and needle—I began to hunt down the original patent. To my surprise, there were no patents under the name of the Fabricon Company or by William or Fannie Bogolub. Searching for “invisible reweaver” brought me to the exact tool I had been searching for, identical in every way to the Fabricon reweaver. The only problem was that it wasn’t by Fabricon. The patent, submitted in 1942 and approved in 1944, belonged to three people: William S. Hieber, Sonia L. Hieber, and Irwin C. Elmer of Atlanta, Georgia.

Unlike the Bogolubs, whose family history could be easily traced through marriages and obituaries dating back to the early 19th century, William Hieber, Sonia Hieber, and Irwin Elmer appeared together only on the patent. I was unable to find any biographical information about Irwin Elmer, though Sonia Hieber and occasionally her husband William did appear in advertisements in The Atlanta Journal and The Atlanta Constitutional throughout the 1940s and into 1951. She ran a mending company, the Dixie Reweavers, and attributed her technique to her Argentinian heritage. A 1941 full page spread promises “a seeming miracle” to “protect your personal appearance” through “genuine” rather than “ordinary” reweaving. An article on Hieber from 1940 entitled “Dixie Reweavers is Outgrowth of Family Hobby” adds that Hieber trained her own reweavers to work in her shop, and her success allowed her to open a second location. A year later, the business celebrated its fifth year with another article that specified the difference between “ordinary” and “genuine” reweaving: genuine reweaving takes threads from the seams of the garments for reweaving, where ordinary reweaving employs the use of commercial threads.

While the only advertisements I could find were exclusive to Georgia, the article notes that the Dixie Reweavers were so known for their skill that they often received garments from across the United States and even internationally. They attributed this success, in part, to war time austerity measures which meant that new woolen garments were increasingly difficult to access. A 1941 article in The Atlanta Journal titled “Scarcity of Woolens Makes Invisible Reweaving of the Dixie Reweavers More Essential” wrote that the company not only dealt in men’s and women’s outwear but also officers’ uniforms. The thrift and material efficiency of mending a hole using spare threads from the seams fit nicely into the mentality of American self-sufficiency.

If the Hiebers and the Bogolubs ever crossed paths or quarreled over the apparent breach of patent, there was never any news coverage of the dispute. The Dixie Reweavers disappeared from the public record in the early 1950s, and the Fabricon Company continued to peddle their correspondence courses into the early 1990s. They were never granted a patent for the method or tool, though they did rather deceptively include “FABRICON TRADEMARK” to the diagram which, to the untrained eye, would suggest that they owned the design and not simply the Fabricon name itself. The Hiebers never took the tool into production, and the patent expired in 1961.

While hobbyist and professional invisible reweavers are willing to pay a premium for the tools, it’s unlikely anyone will take up their production. The skill is increasingly rare, and few tailoring shops offer the service. French American Reweaving Co. in Manhattan, which had six full time reweavers on payroll in the 1980s, has no shortage of business but struggle to find skilled workers. According to an article in the Des Moines Register, by 1993 there were only an estimated 100 trained reweavers in the entire United States. In 2021, French American Reweaving Co. owner Ronald Moore told Business Insider that he currently has only three employees —all over the age of seventy.

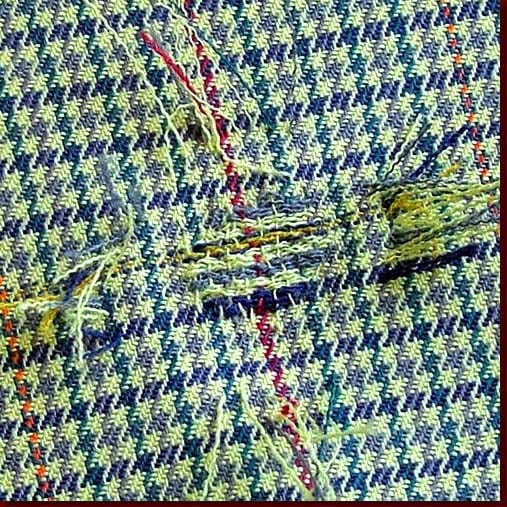

However, if you have a little ingenuity, some inexpensive tools, and a friend with a tiny soldering iron, you too can assemble your own invisible reweaver. After the latch shaft was firmly attached to the guide, I wrapped the handle in a slim cord and then tightly stitched a soft piece of scrap leather to hold it in place and provide a comfortable grip. I armed myself with the handy Magni-Focuser, a fraying fabric swatch, and the reweaver, and set to work. The process of actually reweaving was slow going at first, and I began to realize the extent of my hubris by thinking I could teach myself such a bespoke skill over the course of a single day. And then, after some agonizing practice, I began to get the hang of it.

Like reweaving, textile work requires patience, focus, and lots of practice. That is why it is, and should be, costly. According to the US Labor Bureau, in the year 1900 people in the United States spent an estimated 14 percent of their annual income on clothing. By 2000, that figure had dropped to 4 percent and has continued to trend down over the last twenty years. We expect our clothing to be cheap, and manufacturers are all too happy to cut costs by lowering quality and exploiting workers. Buying something new is easier and sometimes less expensive than having something fixed, especially as those skills become more rare and less appreciated. The Fabricon company tapped into a market of people who wanted to learn a useful skill and become part of a diminishing economic sector of mending garments rather than manufacturing new ones. The skill they taught and the tools they sold were useful and still hold value today. What they failed to advertise was that learning something alone is hard. It takes a certain type of person with a certain type of mind. For most of human history, textile work has been passed down from hand to hand. You watch someone work, you learn to mimic their motions, and you ask for help when you don’t understand.

Trying to pick up invisible reweaving from a long defunct correspondence course reminded me not only of the value of clothing but also the value of learning from a teacher. I certainly won’t be opening up a reweaving practice any time soon! A 1993 write-up in the business section of the Des Moines Article described reweaving as “ant surgery” and, after trying it myself, I am inclined to agree. The next time I find a very small hole in a woven garment, I’ll give it another try. Until then, I’m happy to continue trying new methods of visible mending to invest the time and love into my clothes that they deserve.

Sources

Sources Cited

Barnett, Ronnee, et al. 2006. “Tapestry conservation at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.” Tapestry Conservation: Principles and Practice. Elsevier. Burlington, MA.

Ellwood, Mark. 2021. “Meet the Man Who Fixes the Toughest Clothing Issues for Celebrities and the Ultra-Wealthy and Runs One of the Last Remaining Reweaving Businesses in the Country.” Business Insider. www.businessinsider.com/nyc-reweaver-luxury-clothing-tailor-what-business-like-2021-10.

Coffin, David. 1989. ”Questions.” Threads Magazine 24. Newton, CT.

Hier, Frank. 1955. “Complaint in the Matter of William Bogolub Doing Business As Fabricon Company.” Federal Trade Commission Decisions. Federal Trade Commission.

Jost, Rick. 1993. Smallest of Small Businesses likened to ‘ant surgery.’ The Des Moines Register. Des Moines, IA.

Marino, Joseph. 1998. “Compelling Data Indicating an Invisible Reweave in the C-14 Corner of the Turin Shroud.” Compelling Counter-Inquiry on the Holy Shroud.

Satterfield, Monette. 2012 “Reweaving Damaged Fabric: Patience is a Virtue.” PieceWork Magazine. Interweave Press, LLC. March/April 2012. Loveland, CO.

US Department of Labor, US Department of Statistics. 2006. 100 Years of U.S. Consumer Spending Data for the Nation, New York City, and Boston.

1940. Dixie Reweavers is Outgrowth of Family Hobby. The Atlanta Journal. Atlanta, GA.

1941. Dixie Reweavers Observe Fifth Anniversary. The Atlanta Journal. Atlanta, GA.

1941. Scarcity of Woolens Makes Invisible Reweaving of Dixie Reweavers More Essential. The Atlanta Journal. Atlanta, GA.

1957. “Elk’s Family Shopper.” The Elk’s Magazine. New York, NY

1985. Obituary for Fannie Bogolub. Chicago Tribune. Chicago, IL.

2001. Obituary for William Bogolub. Chicago Tribune. Chicago, IL.

2010. “Fabricon Invisible Reweaver.” Collectors Weekly, www.collectorsweekly.com/stories/719-fabricon-invisible-reweaver.