Spanning from the souks of Aleppo and Damascus to the pastures of New Zealand and Australia, Gigi Matthews has been to over 30 countries. Her studio, the product of her practice as a spinner as well as globetrotter, is a curated sea of fibers and textiles. When we spoke, she pulled various treasures to show me: a constellation of tiny seeds for naturally colorful cotton which she plans to grow on her roof, soft piles of raw wool, and a collection of massive antique combs which— she tells me — double as a bludgeoning tool should the occasion arise.

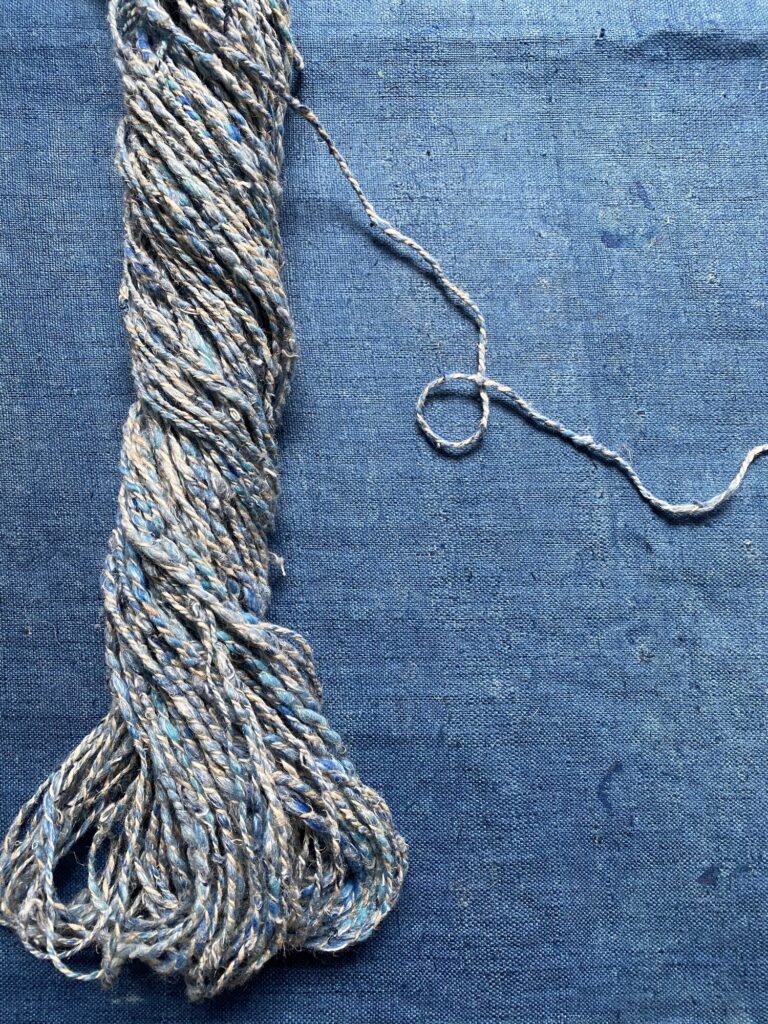

If you have an image of what sheep’s wool looks like, short fluffy white fibers, cast that aside. Gigi is a spinner of “rare breed” strands. Curly pearlescent tufts of gray beside yellows and browns ranging from long fine hairs and tightly coiled ringlets. Rare breeds, she tells me, is actually a euphemism for any sheep wool the textile manufacturing industry has deemed too difficult to work with. But Gigi is one of a handful of spinners worldwide combating the decline of endangered sheep breeds by using the rejected fleece in her practice. She also travels across North America to speak to the importance of sustainable fibers, passionately advocating for immediate action to reform the textile industry.

How did you get involved in rare breed spinning?

There’s an organization in the U.S. called the Livestock Conservancy which has a sheep and wool section cutely named ‘Shave ‘Em to Save ‘Em.’ During industrialization, wool companies only wanted sheep whose wool was easy to dye, so white, and fit conveniently through the machinery of the mill. All these other breeds that used to be extremely popular and profitable dwindled because there was no money in it for the farmers. When you look at the endangered breeds, you’re looking at sheep which have all kinds of qualities that domesticated sheep do not possess anymore. Different color and texture fleece, resistance to diseases like hoof rot, so the reason that we want to try to keep these breeds going is because they keep the gene pool nice and broad. By encouraging spinners to buy rare fleeces from farmers, initiatives like Shave ‘Em to Save ‘Em have actually stopped some breeds from going extinct.

Where do you get your fleeces?

Funnily enough, Etsy is a great source. There’s a shop called ‘The Wychwood Spinner’ run by a woman who specializes in selling fleeces from UK rare breeds. There’s also a wonderful book that came out recently called ‘The Lost Flock’ by Jane Cooper. She’s a knitter who ended up living in the Orkney Islands of Scotland farming Orkney Boreray sheep, which are Scottish breed primitive sheep. You can buy from her online or just search rare sheep farms near you and call farmers directly about buying their fleeces.

By primitive sheep, does that mean that they still shed?

Yes, so primitive sheep are those that were not domesticated for industrial purposes. Some of the really, really rare breeds will still shed or molt and do not need to be sheared. For example, the Orkney Boreray sheep live on an uninhabited island. It is uninhabited because there aren’t freshwater sources there for people to use, but the sheep are there because the Vikings, who sailed the seas for centuries, used sheep wool to make their sails. They seeded sheep on all these islands in the North Sea, all the way through Iceland, so that they would always have a source of wool for their ship sails. Traditionally, the Islanders near Orkney Boreray would go over to the island where the sheep lived once a year and collect all the molted fleece off the grass and brambles to bring home.

If rare wool is your favorite fiber for sustainable textiles, what would be the fiber that worries you the most?

It’s a cross between two, and they’re actually tied in terms of environmental harm: polyester and, surprisingly, cotton. Polyester is plastic, and it sheds micro fibers. They’re finding them in the Mariana Trench, in the Arctic. It’s a massive issue because they are microplastics getting into our food and water supply and in our bodies. It’s so urgent that I compare the situation to when I was in my 20s and they found the hole in the ozone.

At the time, I thought, that’s it: we’re all gonna be dead of radiation poisoning. And it’s the one time in history where every country in the world got behind something and banned pollutants causing the hole. This is the same, it’s essentially a moonshot which requires the resources and cooperation of every country to stop it. So that’s number one. Number two is conventional cotton. When you add up the large scale farming, shipping, processing, and manufacturing, it’s just as polluting. When I do this talk, I don’t want people to suddenly get extremely depressed like me with the ozone layer. There are actually the most amazing things coming through the pipeline in terms of sustainable fabrics and processes. In just the last couple years, so much has been invented. The problem is that it hasn’t actually been scaled up.

What do you think is the primary message you want people to take away from your talk?

One of the things I think is most important with textile sustainability is to change the way that we think about textiles, the way that we value them. I think there needs to be a deeper and more compassionate idea of how we value a textile. Not just ‘does this look good with my decor’ and more ‘was this made in such a way that it caused not only as little harm as possible, but maybe even did some good.’ That’s going to be a slow process. It may take a generation or two to get there. I think people also have to realize that we are over-producing so much. None of us have to buy anything new for at least a couple generations.

Gigi Matthews’ keen interest in the fiber arts is a result of decades of world travel to over 30 countries. From her native British Columbia to the souks of Aleppo and Damascus, markets in Paris to the pastures of New Zealand and Australia, she has gained a deep respect for textile traditions. An award winning spinner, her recent work focuses on sustainability, making use of reclaimed and recycled materials. Gigi has taught handspinning to guilds, at MidAtlantic Fiber Association conferences, and the John C Campbell Folk School and has published articles in Ply Magazine and Shuttle, Spindle & Dyepot. She is on the board of the Handweavers Guild of America.