Despite its relatively recent invention, the zipper is a staple of modern life. From clothing to garment bags, we use it on almost every kind of textile. Re-aligning a zipper is as handy a skill as resewing a button: getting trapped in a zippered garment is the subject of sitcoms and the terror of anyone who has found themselves in a store changing room blindly groping for a pull tab. Like many things we use on a daily basis, we rarely think about zippers until confronted with a malfunction. Today, on National Zipper Day, we invite you to follow the zipper’s meteoric rise and its shifting place in an increasingly environmentally conscious fashion industry.

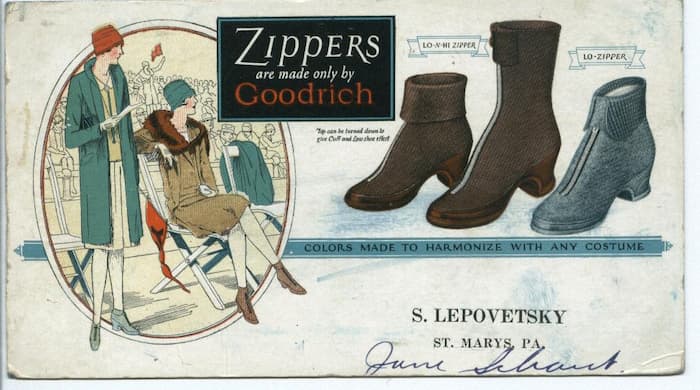

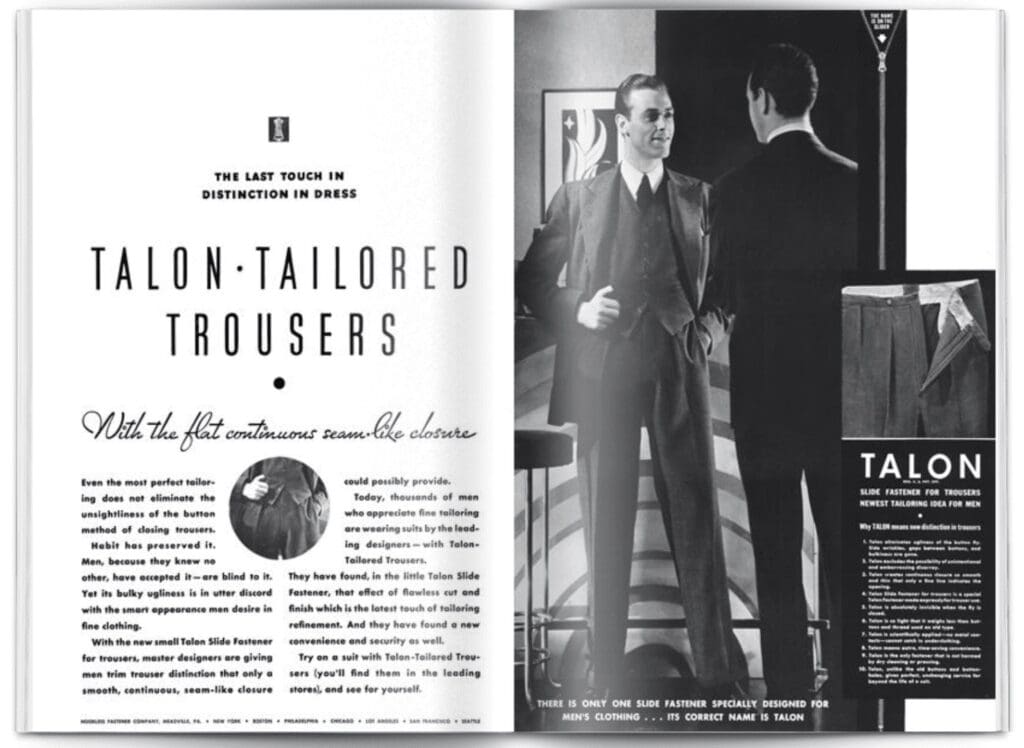

As with most of the inventions of the mid to late 19th century, the zipper went through multiple iterations before it caught the public interest. In 1851, Elias Howe patented the ‘automatic, continuous clothing closure.’ The next iteration of the zipper, the Whitcomb Judson ‘clasp locker’ debuted at the 1893 World’s Fair as a hook and eye fastener for shoes. It wasn’t until 1917 that Gideon Sundback of the Universal Fastener Company patented the modern day zipper under the name ‘the separable fastener.’ Primarily used for boots and tobacco pouches, the zipper didn’t get its name – or its real popularity – until 1923 when the B.F. Goodrich Company used Sundback’s separable fastener on a pair of women’s rubber boots called ‘The Zipper.’ The name stuck, and the newly minted zipper quickly moved from novelty to necessity. It was quicker, easier, more streamlined, and more secure, not only the invention of a rapidly moving modern society but one which encouraged growth and at speed.

True to its name, the zipper quickly outpaced buttons and laces. Elsa Schiaparelli of the Schiaparelli Fashion House was one of the first high fashion designers to embrace the zipper in the mid 1930s, not only as a hidden feature but as a prominent and functional design element. A green Schiaparelli gown in the MET collection, with matching shoes by famed shoe designer André Perugia, features a prominent gold zipper on the side seam. Her 1938 collaboration with Salvador Dalí resulted in one of her most iconic garments, the skeleton dress. Considered an “offense against good taste,” the dress included large plastic zippers on both shoulders and down the right seam.

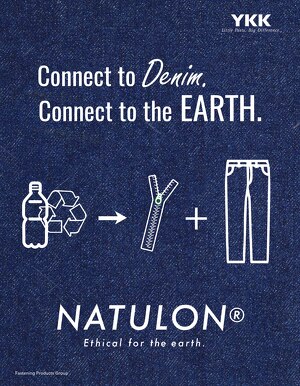

Almost a hundred years later, zippers are cheap, versatile, and everywhere. They are also an environmental and ethical nightmare. The demand for cheap, fast fashion over the last two decades especially encourages manufacturers to cut costs. The plastic zipper is cheaper than its metal counterpart, and increasingly more popular. Every time a plastic zipper goes through the laundry, it breaks down slightly. This releases microplastics into the water, contaminating marine environments and often working its way back up in the food chain to humans, and increases the likelihood of a zipper malfunction. In an age where clothing is treated as disposable, people are more likely to throw away a garment than they are to fix the broken element. Even metal zippers produced by fast fashion houses rely upon lead as a cheap but toxic filler metal to cut costs. Repeated exposure to lead is not only dangerous for consumers but can be deadly for garment workers.

More than nine thousand years ago, as clothing design began to move away from whole cloth fabrics to cut and sewn textiles which were more tailored to the body, the button was invented both as decoration and utility. It allowed for slimmer silhouettes and clothing which required less time – and assistance – to put on and take off. Laces, buttons, pins, buckles, belts, pleats, and even elastic panels far predate the zipper as tools for more tailored shapes. The truth is that as silhouettes get tighter, clothing becomes necessarily more disposable. Most clothing today isn’t made to grow and change as your body inevitably does. If you have ever battled with the zipper of a once dependable pair of pants, you know all too well the pitfalls of fast fashion design. Sustainable, low waste garments are not only made to reduce their impact on the environment: they are made to follow you through multiple phases of your life. This is not to say we need to abandon the zipper wholesale: companies like Rudholm Zips and even the world’s biggest zipper manufacturer, Yoshida Kōgyō Kabushikigaisha (YKK), are working on making zippers from recycled plastic and biodegradable materials. Still, it is worth thinking about the fact that zippers have only been around for a little more than a hundred years. Maybe silhouettes of the future should be less concerned with fit, and more concerned with flexibility: for the longevity of our wardrobes and the longevity of the only home we have.

FURTHER READING AT TATTER

Barber, Elizabeth Wayland. Women’s Work: The First 20,000 Years, Women, Cloth and Society in Early Times, Elizabeth Wayland Barber. W.W.Norton, 1994. call number GN799.T43.B37

Bruna, Denis. Fashioning the Body: An Intimate History of the Silhouette. Yale University Press for Bard Graduate Center, 2015. call number GT2073.B78

Epstein, Diana, Safro, Millicent Buttons Harry N. Abrams Inc. New York, New York. 1991 call number NK3668.5.E6.1991

Walford, Jonathan. Forties Fashion from Siren Suits to the New Look. Thames & Hudson, 2011. call number GT596.W35.2008Weaver, Susan Faulkner. Handwoven Tape. Schiffer Publishing, 2016. call number TT869.7.W4

REFERENCES:

Barber, Elizabeth Wayland. Women’s Work: The First 20,000 Years, Women, Cloth and Society in Early Times, Elizabeth Wayland Barber. W.W.Norton, 1994.

Bruna, Denis. Fashioning the Body: An Intimate History of the Silhouette. Yale University Press for Bard Graduate Center, 2015.

Epstein, Diana, Safro, Millicent Buttons Harry N. Abrams Inc. New York, New York. 1991

French, Design House Schiaparelli, and Designer Elsa Schiaparelli Italian. “Schiaparelli: Evening Dress: French.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/157228.

Friedel, Robert D. Zipper: An Exploration in Novelty. W.W. Norton, 1994.

Hawkes, Sonia. “Some Recent Finds of Late Roman Buckles.” Britannia, vol. 5, 1974, pp. 386–93. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/525745. Accessed 23 Apr. 2024.

Italian, Designer Elsa Schiaparelli, and Designer André Perugia French. “Elsa Schiaparelli: Evening Ensemble: French.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/155853.

McNeil, Ian. An Encyclopaedia of the History of Technology. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2005.

“Shoe Icons / a Pair of Ladies Brown Glacé Leather Ankle Boots with Elasticated Sides and Curved Heels.” Shoe Icons /, eng.shoe-icons.com/collection/object.htm?id=2373.

“The Skeleton Dress: Salvador Dalí: Elsa Schiaparelli.” Victoria and Albert Museum: Explore the Collections, collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O65687/the-skeleton-dress-the-circus-evening-dress-elsa-schiaparelli/the-skeleton-dress-evening-dress-elsa-schiaparelli/.

“Sustainable Zippers.” IDEAL Fastener Corporation, 27 Nov. 2023, idealfastener.com/sustainable/.

“Talon Tailored Trousers.” Esquire Magazine , no. Autumn, 1 Sept. 1933.

Ucl. “UCL Petrie Museum’s Tarkhan Dress: World’s Oldest Woven Garment.” UCL News, 6 May 2022, www.ucl.ac.uk/news/2016/feb/ucl-petrie-museums-tarkhan-dress-worlds-oldest-woven-garment.

Walford, Jonathan. Forties Fashion from Siren Suits to the New Look. Thames & Hudson, 2011.

Weaver, Susan Faulkner. Handwoven Tape. Schiffer Publishing, 2016.“YKK Begins Manufacturing Eco-Friendly Zippers in the USA.” YKK Americas, 9 June 2023, ykkamericas.com/ykk-begins-manufacturing-eco-friendly-zippers-in-the-usa-2/