The term ‘domestic arts’ and its later iterations—’home economics’ and ‘consumer and family sciences’—have long histories in the United States. Each evolved from instruction in home maintenance, with each name change reflecting shifting educational approaches during the past two centuries. These histories are inseparable from classist, gendered, and racist frameworks that continue to evoke polarized responses. This is precisely what interests me as a researcher: understanding how such caretaking practices are transformed by culture, because there is nothing inherent in these practices to suggest that one type of person is more suited to them than anyone else. My investigation becomes a process of reading objects for context, looking closely at material evidence, and questioning established narratives about who creates domestic art and why.

What, precisely, are domestic arts? Can they be considered art in their own right? Do they constitute an artistic practice? Is this another domain of human creativity that has gone unrecognized as craft or art?

What this research project, affectionately named domestic artist, presents is not a history, but a lens to explore why domestic art is valuable to its practitioners, its recipients, and to cultural history. Everyone can be an artist if you know how to look.

When considering this collection of objects as a whole, it’s important to acknowledge their selection as an act of collaboration and creative interpretation. Before my research visit, I asked Ida-Rose Chabon (Tatter’s Object Collection Archivist) to pull items related to domestic arts, but deliberately avoided providing a set definition or criteria. Although this may read as sloppy research prep, it was a deliberate action that presented the concept as open for interpretation. I am curious to learn what the term means to others, how they approach it, and what boundaries already exist.

As researchers and creators, we often feel pressure to claim authority over concepts we study. Yet with domestic artist, the process of collective meaning-making proves more valuable than any singular definition I might assert. Many of Ida-Rose’s reflections overlapped with my own, but introduced a new layer that I hadn’t considered (more on that in my lecture). Releasing control over what I think domestic art means has become critical to understanding the project’s richness.

The beauty of re-examining domestic arts not just as a field of study or social history lies in our potential to reclaim creative agency within these practices. Art emerges not exclusively as a material product but an expression.

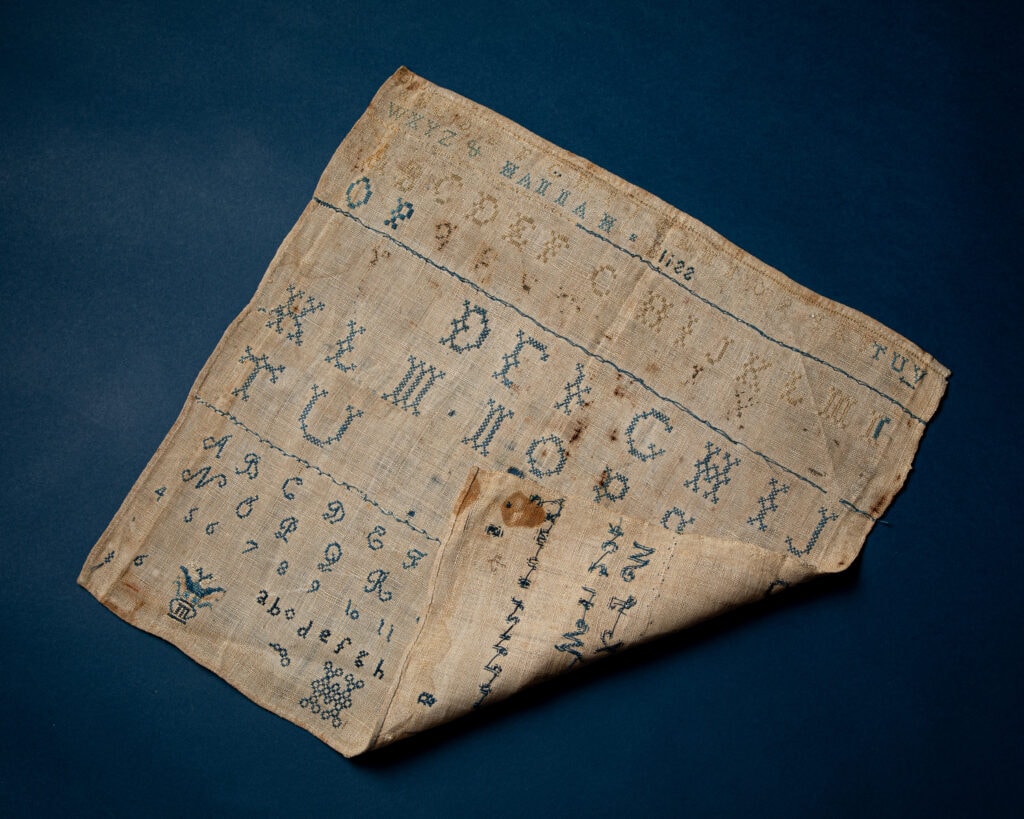

Hanna Bliss Sampler: “School Girl Art”

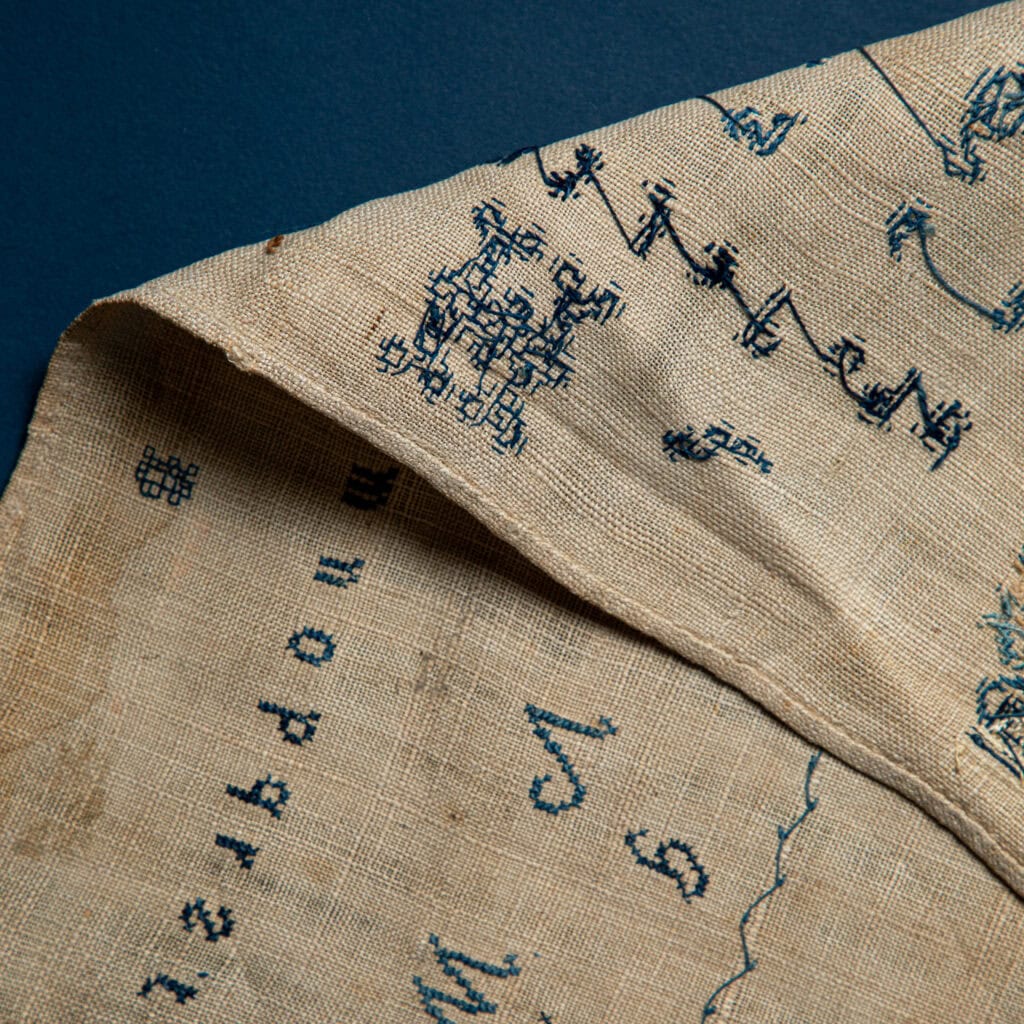

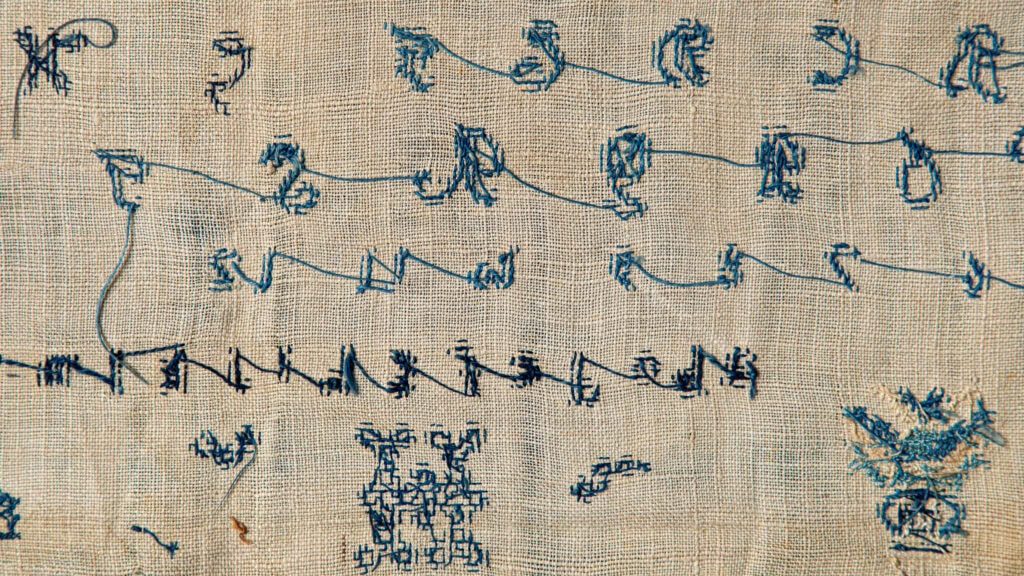

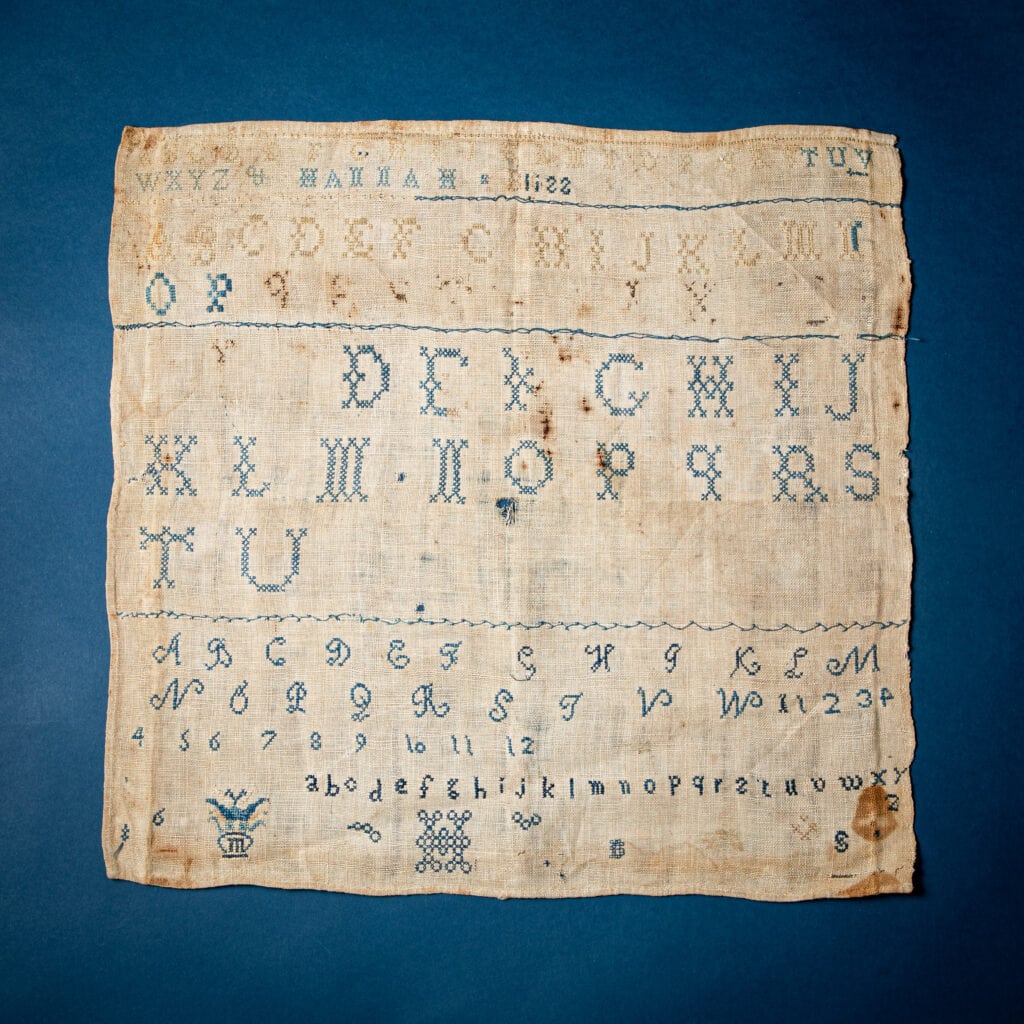

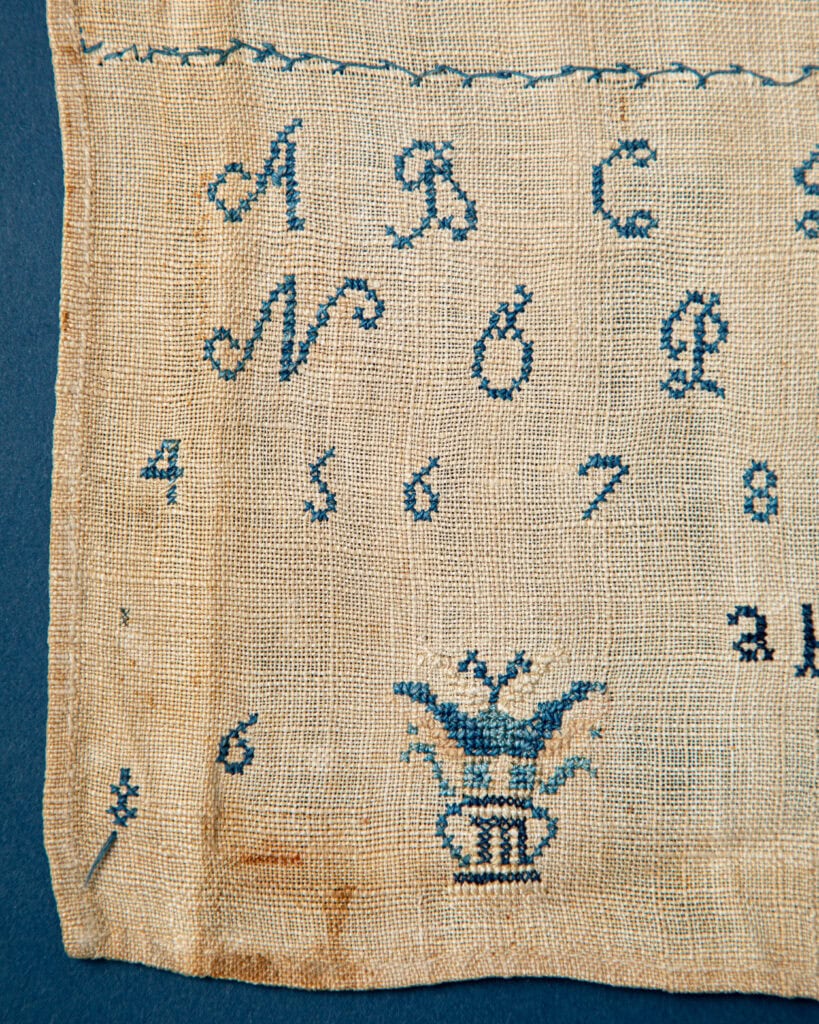

Sampler, Hanna Bliss, likely American, 19th century, silk thread on cotton. (2025.4.7)

A sampler is an easy place to start our search of domestic artists, since needlework has become increasingly collected, analyzed, and (somewhat) accepted as art in American institutions, aided by feminist scholarship that reinserted “women’s work” into historical narratives. By the time Hannah Bliss embroidered this “marking” sampler—a type specifically created to practice lettering and numbering for marking household linens—the form had long since transitioned from displays of professionals’ work to educational training tools. The familiar rows of letters and numbers exemplify the sewing skills taught in early childhood domestic art education. Are Bliss’s irregular spacing, missing, and reversed letters a signal of skill, personal choices, or preservation?

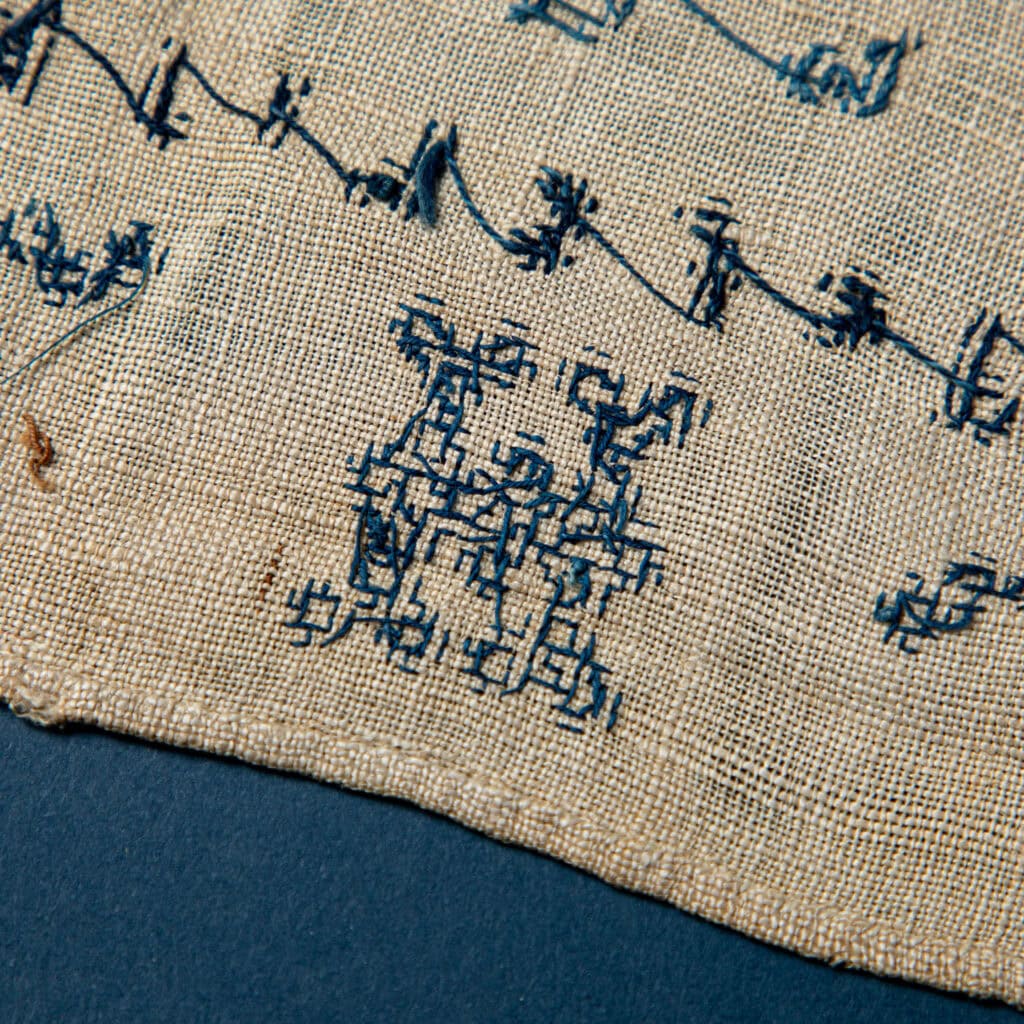

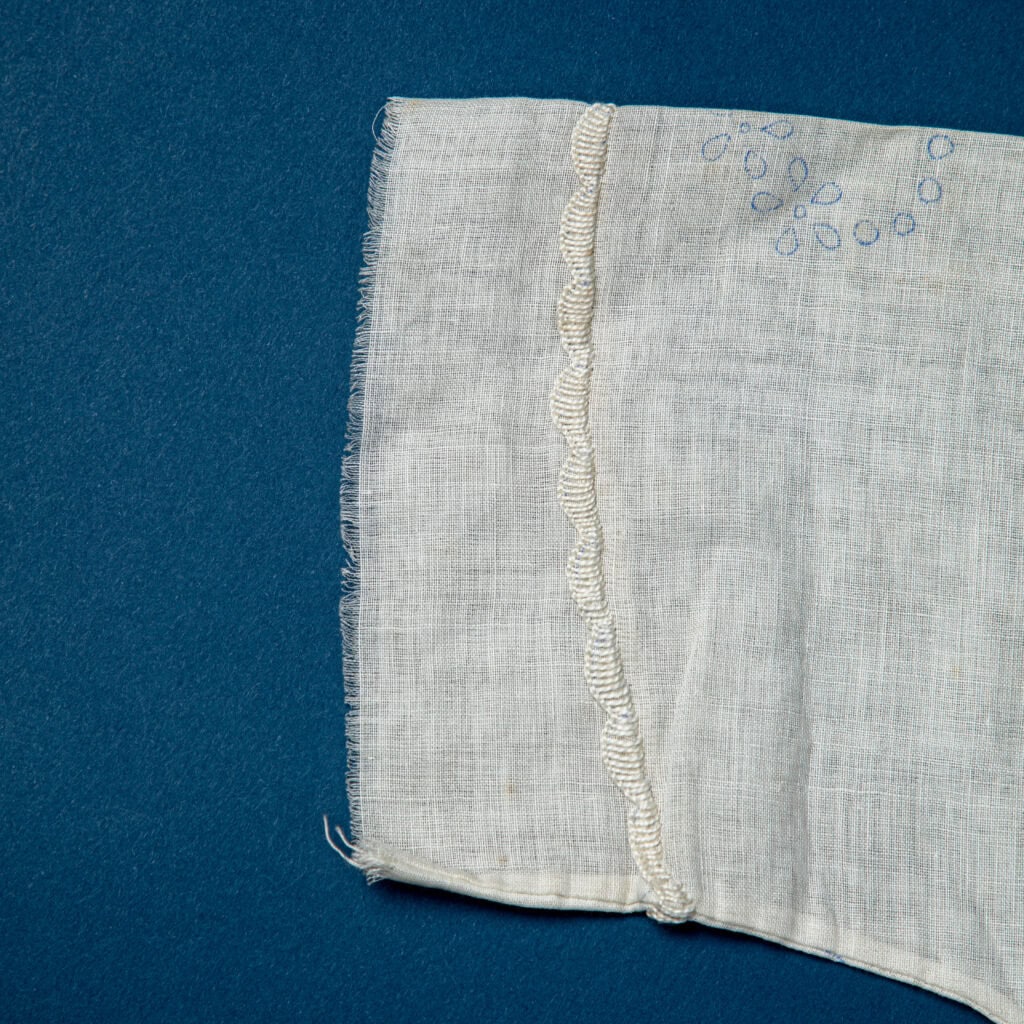

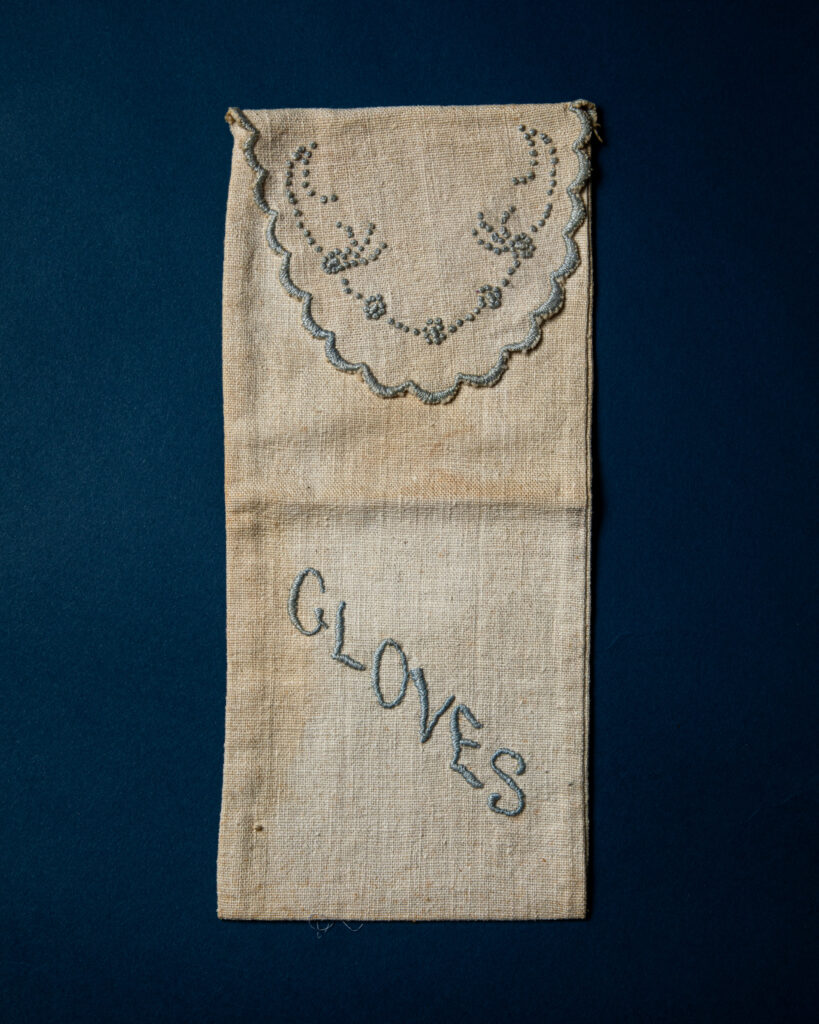

Toddler Dress & Glove Case: Following the Line

Unfinished child’s dress pattern, produced by Embrolyn company, American, 20th century, cotton. (2025.4.8)

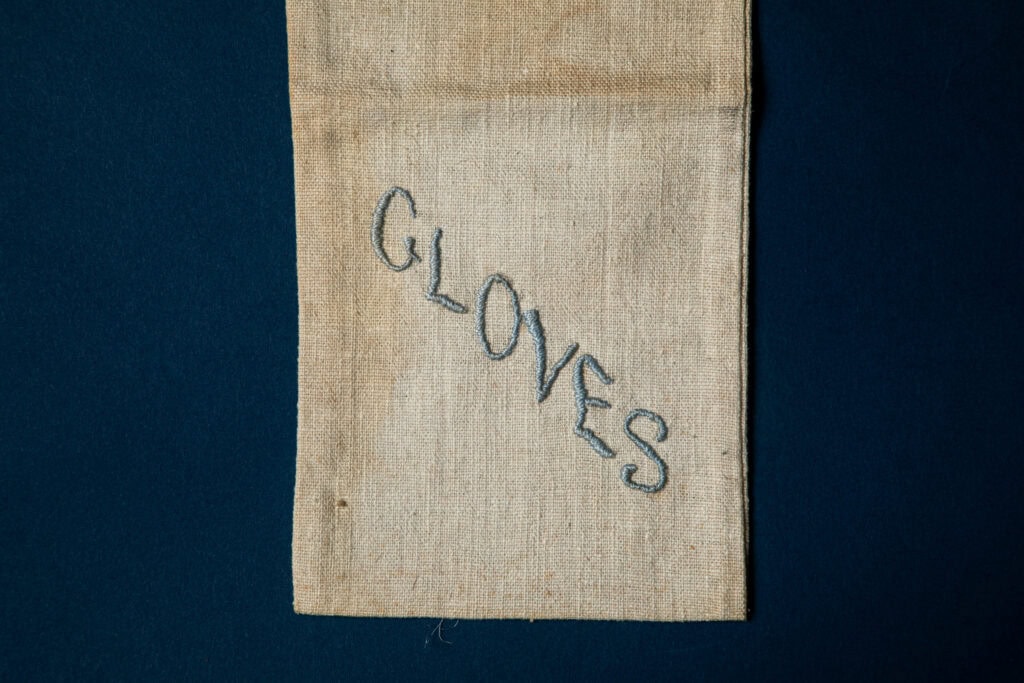

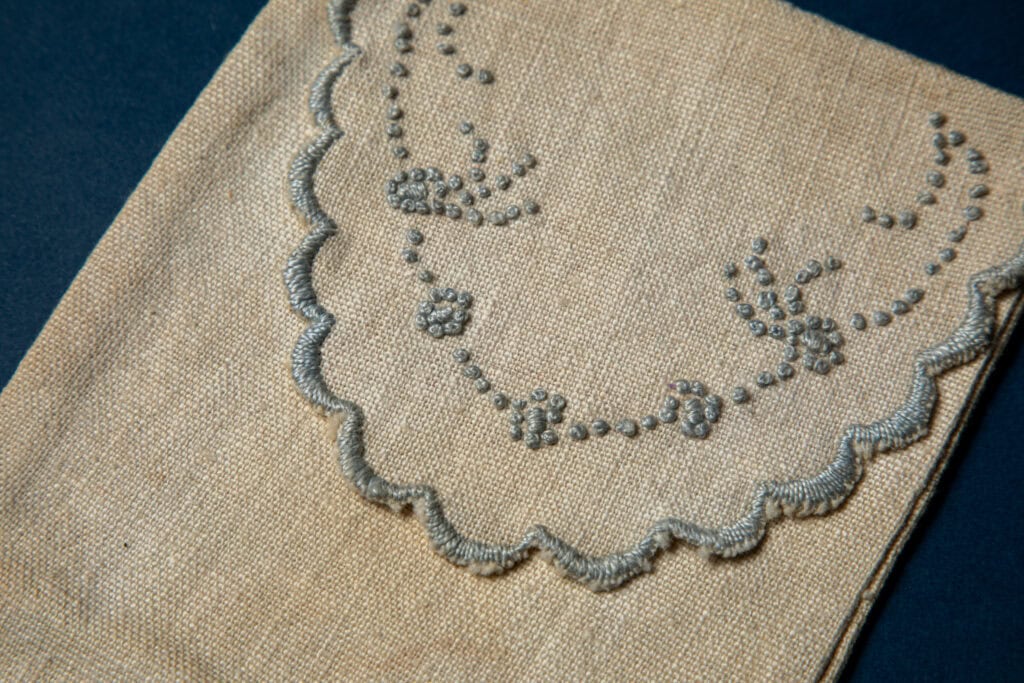

Embroidered glove bag, unknown maker, American or British, 20th century, silk thread on cotton. (2025.4.2)

The sampler could represent either the culmination of an art practice or serve as a gateway to more advanced projects, such as garment construction and decorative embellishments. Consider this child’s dress and glove case, both created from patterns transferred onto fabric before construction. The initial design process raises fundamental questions about creative practice: Does following a predetermined pattern diminish the artistic value of the work? And when a maker deviates from the established pattern—whether deliberately or accidentally—does this represent a flaw in craftsmanship or rather the emergence of a personal signature?

Rosette/Yo-Yo Pillowcase: Functionality

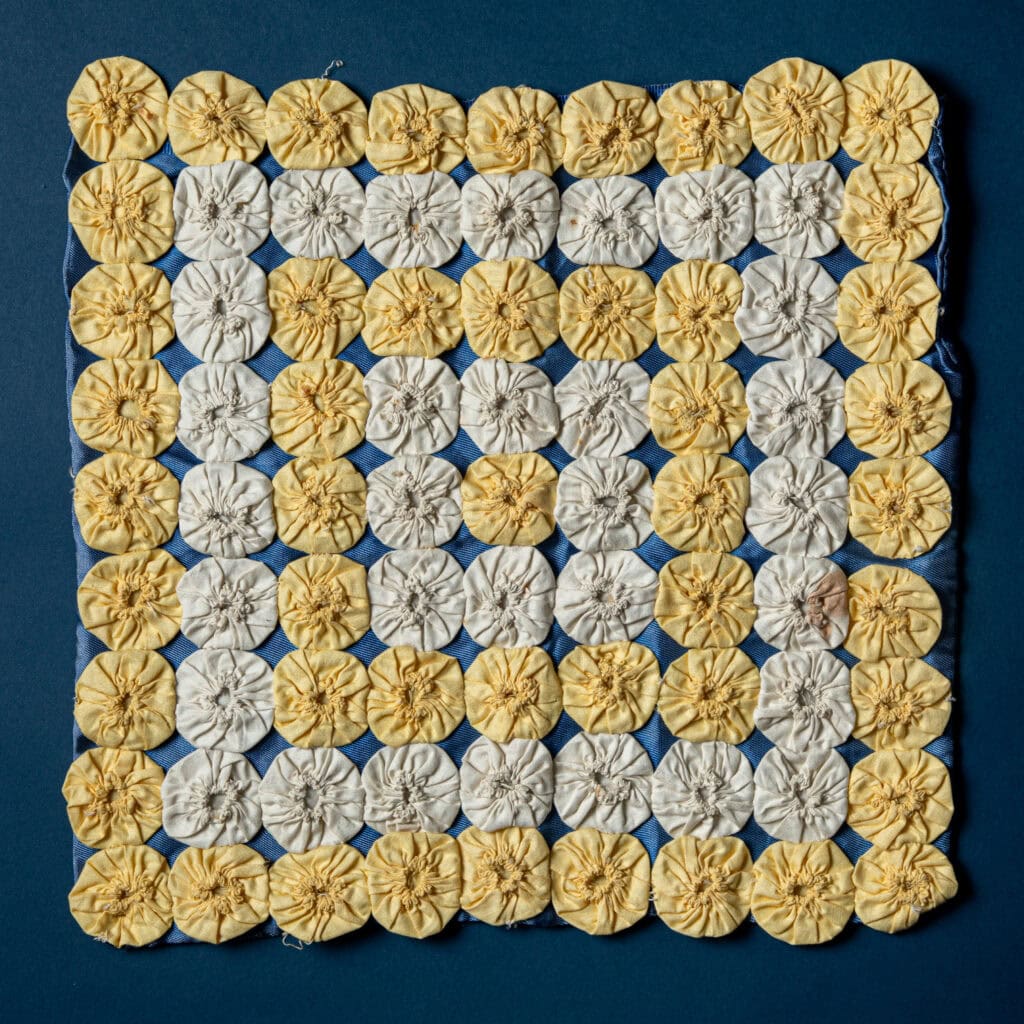

Yo-yo quilted pillowcase, unknown maker, likely American, 20th century, cotton on nylon. (2025.4.4)

The Standard Book of Quiltmaking and Collecting, published in 1949, described the yo-yo quilt as “decorative but, lacking an inner lining, has no utility purpose.” But what limitations do we impose on the idea of utility because of inherent bias? The word refers to something being “useful” amongst other things that could still relate to its multiple functions. There isn’t just one way of working or one singular purpose for everything. Creative expression is a function. Repurposing fabric is a function. Decoration is a function.

Travel Laundry Lines: Take Care

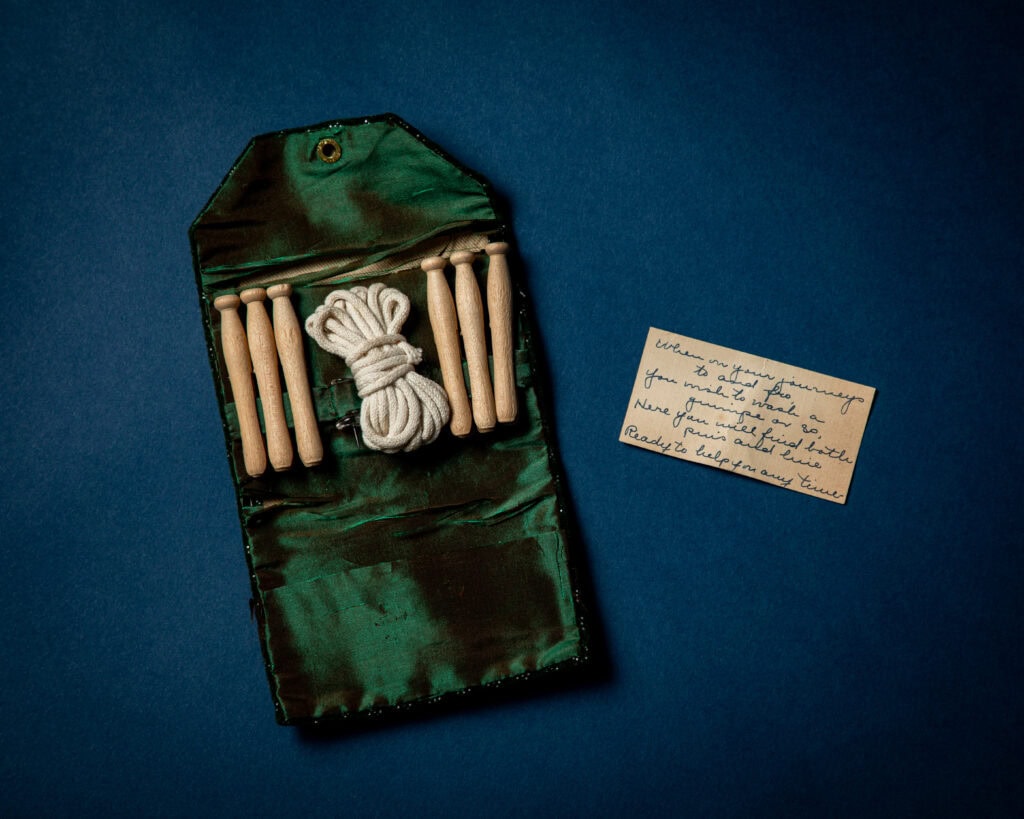

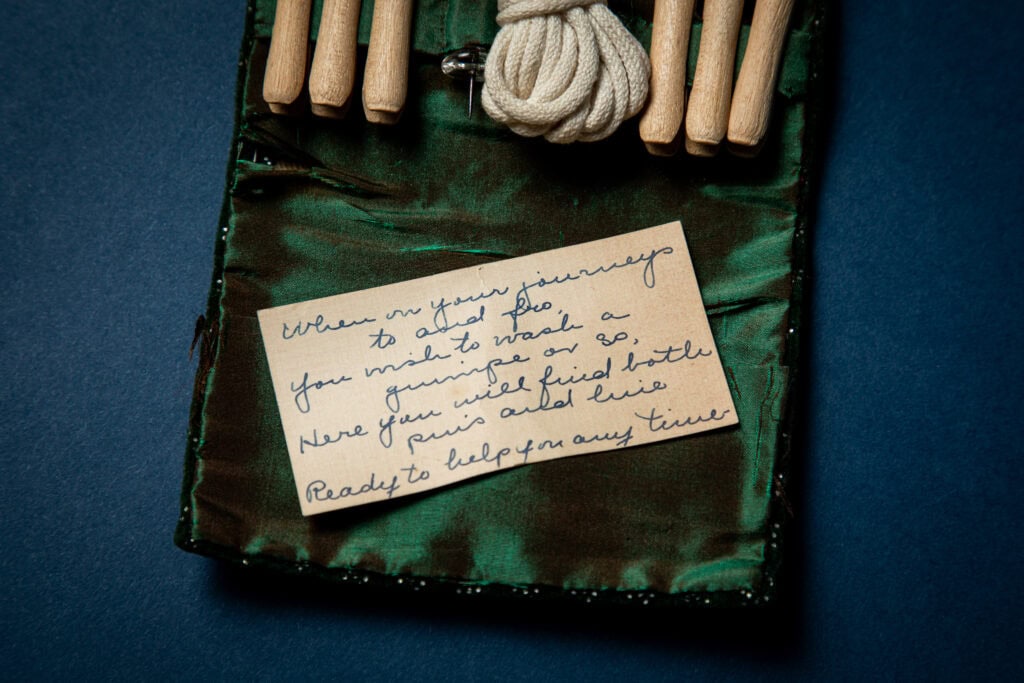

Laundry pin set, unknown maker, 20th century, fabric case and vegetable ivory pins. (2025.4.10)

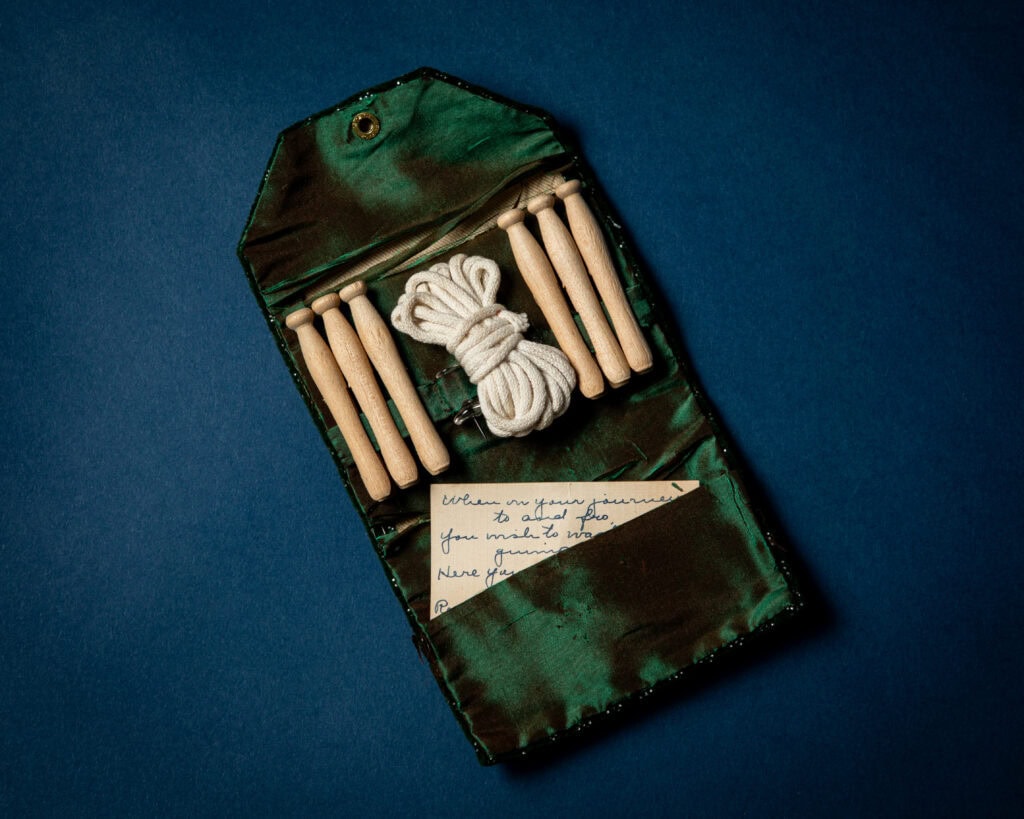

Travel laundry set, unknown maker, 20th century, velvet, silk, wood, twine, glass, metal, paper. (2025.3.2)

The negative aspects of domestic labor are frequently associated with the drudgery of routine maintenance, especially laundry. From preparation to putting away, the process requires time, even today when washing and drying are outsourced to machines. These two compact travel laundry kits remind us that we take our domestic practices with us, extending home routines into public or transient spaces. Yet it is easy to overlook the creative ingenuity in these everyday objects: the thoughtful design, the decorative elements that transform utilitarian tools into aesthetic expressions. In these smallest actions and objects, we find examples of care and creativity. The beauty of the objects dignifies mundane tasks, and the accompanying handwritten note—“Ready to help you anytime”— transforms the toolkit into an artifact of shared artistic practice in a community.

Aprons: Embodied Ideals

Blue plaid apron, unknown maker, 20th century, cotton. (2025.4.9)

Chicken scratch embroidered doll apron, unknown maker, 20th century, cotton thread on cotton fabric. (2025.4.3)

Although the craftsmanship in creating these two aprons could be the creative action, their importance lies in their use. Perhaps more than any other object, the apron represents the symbol of a domestic artist, transforming the wearer into a practitioner. The identity shift transcends scale—the blue bib style for adult size and the navy gingham doll size. The apron becomes both a practical tool and a performative costume, announcing that one is engaged in creative domestic work—cooking, gardening, cleaning—be it in real kitchens or imaginative play.

ATTEND DOMESTIC ARTS: A VIRTUAL LECTURE WITH SARAH BYRD

A love of all things “old” led Sarah to collections and preservation of the past in order to understand the present. This passion informs her work at every level. Her independent research focuses on the role of archives and museums in fashion education, the history of clothing within American cults and communes, and the concept of domestic artists. She firmly believes that education is the key to all progress and strives to connect with audiences beyond the standard classroom setting.

As an archivist, she has worked on a wide range of fashion and textile-based projects for private clients and large corporations.

Since 2017, Sarah has worked with the Textile Arts Center on a textile-based research and history course for the Artist in Residence series. She also teaches courses related to fashion and textile history, museum theory, and fashion archives at the Fashion Institute of Technology, Parsons School of Design, and New York University.

Sarah received her BA from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, and her MA in Fashion and Textile Studies from the Fashion Institute of Technology. Sarah is also a co-founder of the Fashion Studies Alliance, a New York-based network and support system for professionals working in the field of Fashion Studies.