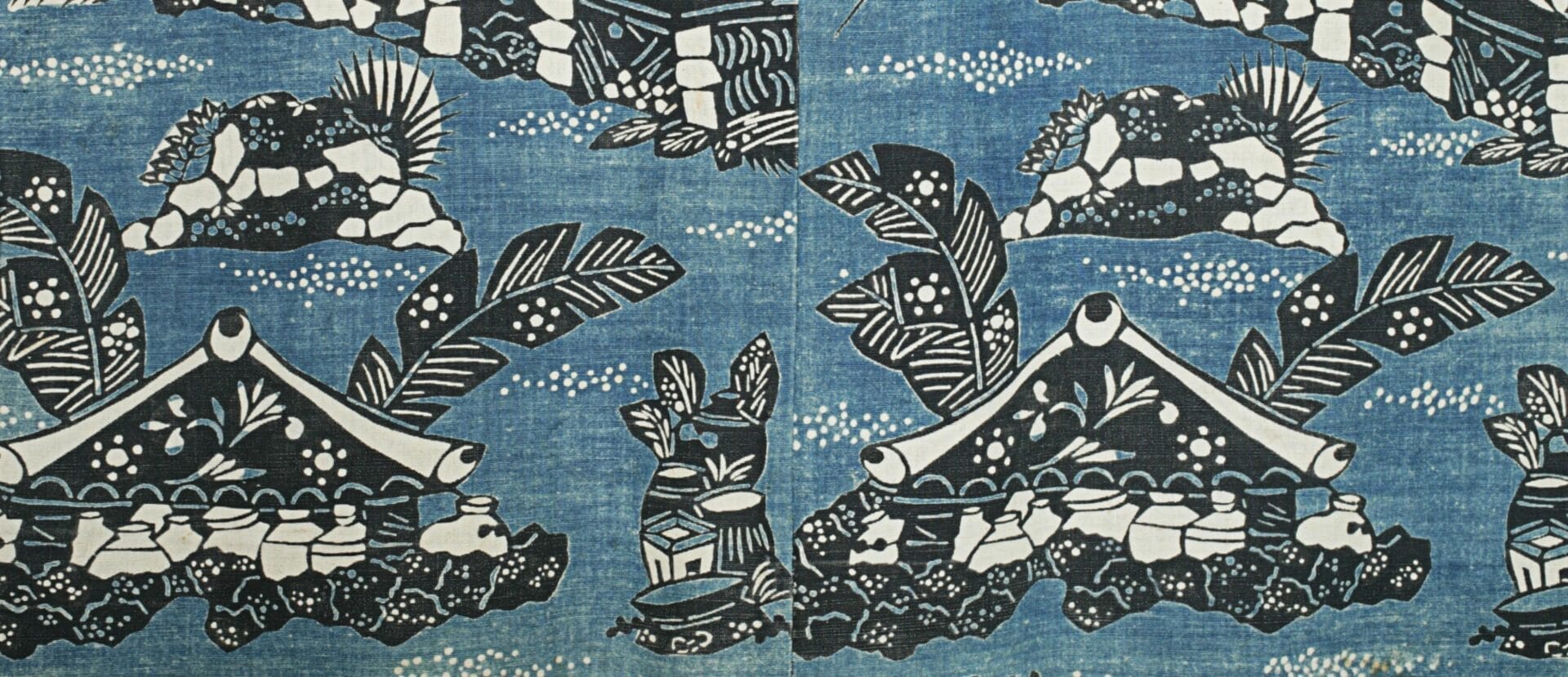

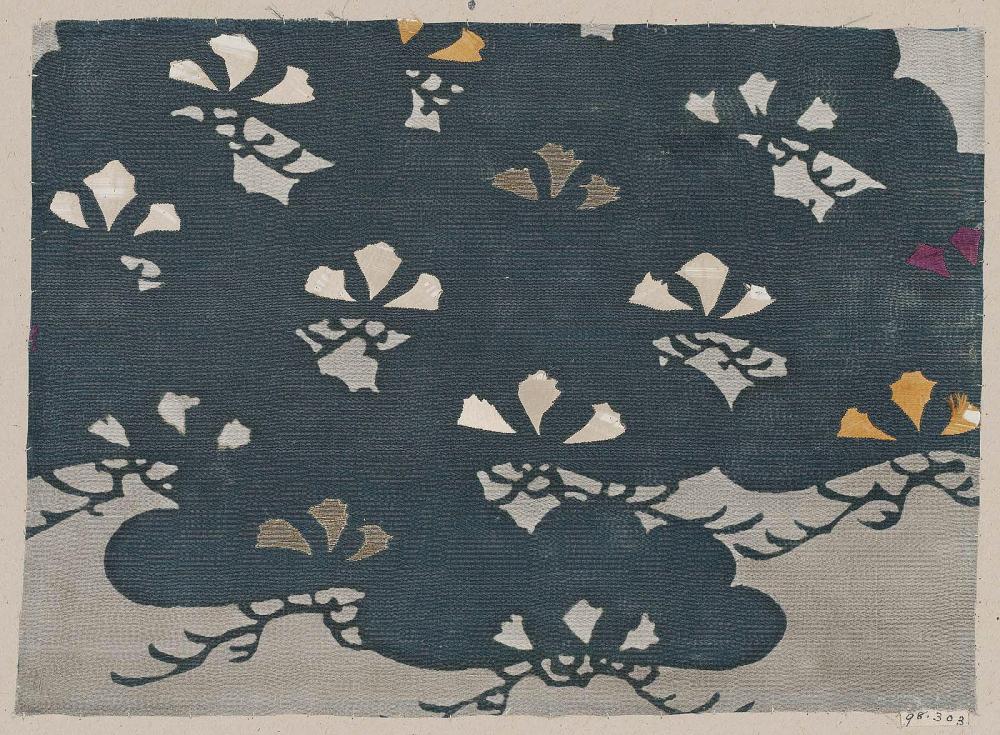

In Japanese, textile production is organized into two categories: sakizome, textiles produced by weaving pre-dyed yarns, and atozome, textiles produced by dyeing pre-woven fabrics. A traditional technique of creating atozome is Katazome (“Kata” meaning “mold” and “Zome” meaning “to dye”), a method of resist-dye work. Using rice paste applied to fabric through katagami (paper stencils), patterns are transferred onto textiles. When the fabric is dyed, the areas covered in rice paste are protected and remain their original color. Indigo—ai—is most often used with the katazome practice, traditionally creating vibrant blue and white textile compositions with floral, vegetal, and geometric patterning.

Katazome stencils, known as shibugami, are traditionally made from several sheets of kozo (mulberry) paper laminated together with persimmon juice, which provides a strengthening and water-resistant coating. Various methods of cutting are used to create the variety of cut-outs that define the completed designs: the oldest method, kiribori (awl cutting), creates small dots; tsukibori (thrust cutting) uses a stenciling knife to create figurative designs; dogubori (tool punching) uses shaped blades to punch out designs; and hikibori (pull cutting) creates fine lines. For very complex designs, artists often use two stencils, an omogata (main stencil) and a keshigata (erasing stencil). Following the rice paste’s application onto fabric stretched on long boards, a sizing liquid—often soy-based—is brushed over the entire textile. After the fabric is immersed in a dye vat and dried, the paste is washed away, leaving a final pattern. Traditionally, a separate artisan is responsible for each step of the process.

The use of stencil decoration in Japanese art dates back to the Nara period (646-794 C.E.), albeit first to adorn paper. Stencils were also utilized in the Kamakura (1185-1336) and Muromachi (1336-1573) periods to decorate leather used in military armor. One of the earliest uses of stencil decoration on textiles in Japan was to ornament formal garments of the Samurai, as well as the clothing of the elite, throughout the Edo period (1603-1897). By the middle of the Edo period, a large-scale stencil-resist technique, known as chūgata, became popular for the decoration of clothes and household items. Following the Meiji Restoration of 1868 and its resulting rapid industrialization, the Japanese textile industry became increasingly automated and mechanized, as well as more focused on producing Westernized dress. Traditional artistic techniques like katazome waned in popularity until the Mingei (folk craft) movement of the 1920s brought about the resurgence of Japanese folk art techniques.

One of the founding artists of the Mingei movement was Serizawa Keisuke (1895-1984), who specialized in resist-dye work, particularly katazome. His textile works utilize incredibly dynamic pictorial expression in complex compositions of Japanese theatres and villages and calligraphic designs, as well as colorful images of flowers, animals, and spiritual figures. In 1956, when Serizawa was named Holder of an Important Tangible Cultural Property, the Committee for the Preservation of Cultural Properties created a new category of atozome specifically for him, kataezome (stencil-picture dyeing). This recognition reflected the richness of Serizawa’s designs, which were much more complex than the traditional historical compositions, as well as his involvement in every stage of the production process of his textiles.

Many contemporary Japanese textile artists utilize katazome in celebration of the craft tradition, while many employ the ancient method to produce entirely modern works of textile art. The flexibility of this practice allows artists the freedom to create dynamic compositions with layers of stenciled designs. Matsubara Yoshichi developed a technique of using in succession stencils of the same shape in diminishing size to produce penetrating patterns that have an illusion of depth. Chinatsu Nagamune uses katazome to “create patterns from markings [she sees] around [her].” Tomie Nagano, a Japanese quilt artist based in Japan and Massachusetts, pieces katazome-dyed indigo cotton into visually complex quilted compositions. Rumi Rock, a Japanese fashion brand founded by designer Rumi Shibasaki, uses katazome to create flamboyant patterns on kimonos. Another contemporary clothing designer, Jōtarō Saitō, uses traditional methods to create kimonos and yukatas (summer kimonos) that reflect contemporary “street” designs.

Experience ai katazome for yourself at Tatter’s immersive textile retreat in Maine, taught by Chinatsu Nagamune, June 18th-23rd, 2023!

Faulkner, Rupert. Introduction to Japanese Stencils, 7-11. Exeter: Webb & Bower Limited, 1988.

Jackson, Anna. Japanese Country Textiles. London: The Victoria & Albert Museum, 1997.

McCarty, Cara and McQuaid, Matilda. Structure and Surface: Contemporary Japanese Textiles. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1998.

Mizuo, Hiroshi. “Serizawa Keisuke: An Appreciation,” in Serizawa: Master of Japanese Textile Design, edited by Joe Earle, 93-96. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.