Hindus around the world will celebrate Diwali tonight lighting millions of diyas, little cotton-wicked terracotta clay lamps lit with oil to mark the arrival of light and with it, hope. No matter how dark things may seem, a glimmer of light leads the way out of the shadows towards a new beginning. This is truly the message of Diwali, our festival of lights.

Observers of Diwali light fireworks, play cards for good luck, make offerings to Mahalakshmi, the Goddess of Wealth, eat lots of sweets and dress up in new clothes to mark a fresh start. Wearing new clothes to celebrate new beginnings isn’t unique to Hindus. Muslims do the same on Eid as do many Christians on Christmas Day.

I’ve spent my twenty-plus year career in fashion and textiles making clothes responsibly from handmade artisanal fabrics and ran an ethical fashion shop in Brooklyn, NY for a decade. Since closing my boutique over a year ago, I’ve bought few unworn items of new clothing and prefer instead to thrift and shop for high quality vintage pieces. For me, buying new clothing off the rack has lost all luster when our landfills are filled with textile waste. At the end of day, is making and buying new stuff really sustainable?

But what of the cultural tradition and the good luck that comes with dressing up in new South Asian finery during the festival season? Dear Reader, have you ever been to an Indian wedding? If you have, you know there’s no such thing as extra at a South Asian celebration. Don’t for a second consider showing up without some serious sparkle embellished on your threads to bring out the bling of your jewelry. Forget about wearing the same thing two years in a row or sporting a used item of clothing from anyone other than an immediate family member. That would be a ‘no-no’ in my mother’s household, and culturally, most South Asians I know continue to eschew the practice of buying used clothing despite its meteoric rise trending among American youth. (My teen students and tween daughter can confirm.)

In 2020 at the height of the pandemic, my husband, daughter and and I moved to my hometown of Greensboro, North Carolina to live near my parents. My mother Veena is known for many things, including her magnificent collection of handloom saris, some of which are over 60 years old. For as long as I can remember, her friends and their daughters showed up before parties for her to expertly wrap them in brocades, chiffons, and painted silks before going out on the town. Since moving near my parents, invitations to gatherings from friends are frequent and when accompanying my impossibly elegant mother to an event, Indian dress is non-negotiable.

After a few months of non-stop events in late 2021, my mother mentioned that the rotation of my fancy dresses needed an update and suggested I start wearing saris.

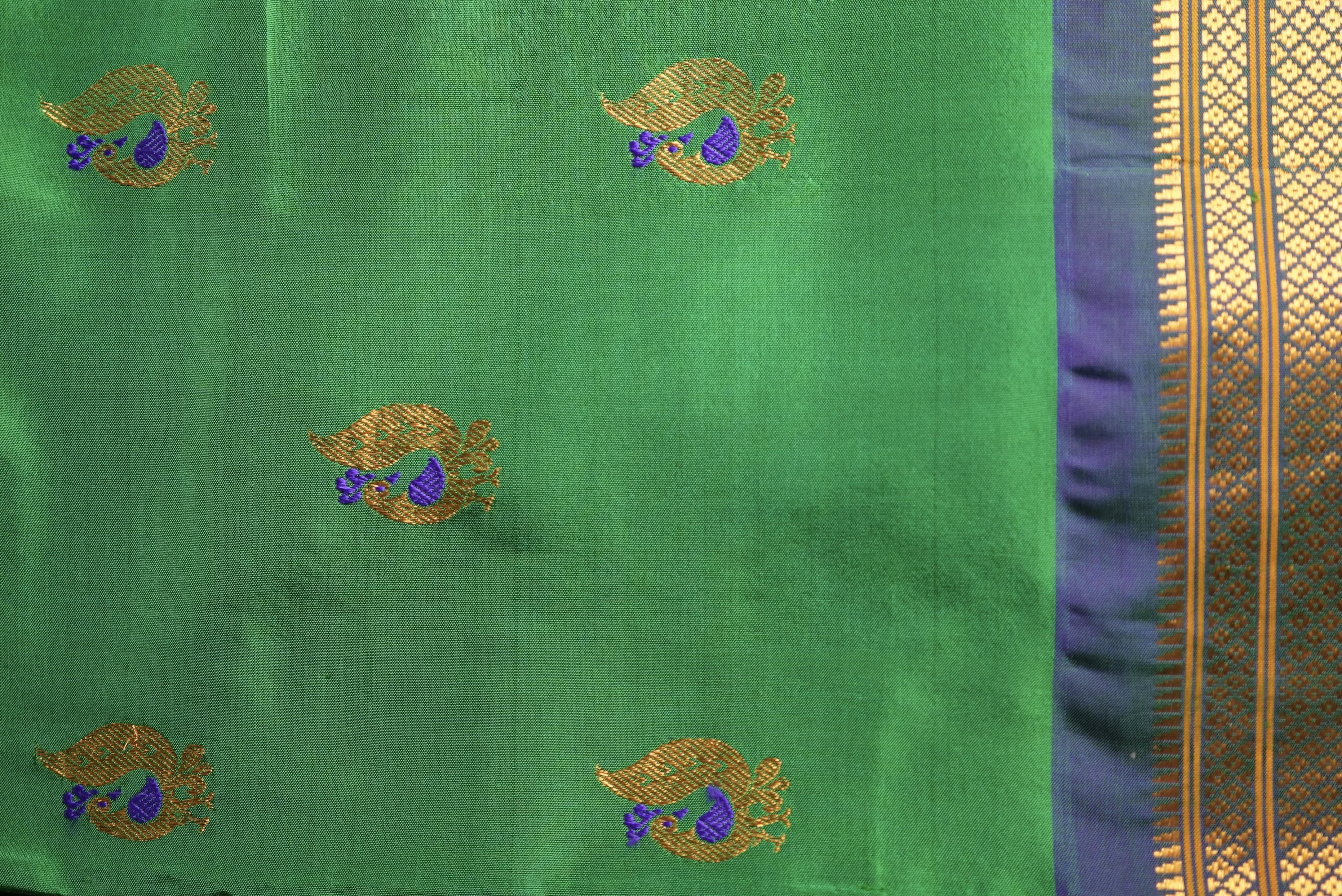

Her sari trunks contain neatly folded stacks of almost exclusively handloom saris anchored by ancient hand weaving practices – many of which are endangered – from countless villages in every state of India. Each weaving region has distinct visual motifs and a unique hand linked to the variety of cotton or silk harvested in its region. With an average length of six yards and a width of forty-four inches, a sari contains within its cross threads eighteen feet of stories about home, craft, distance and family. Each bolt of material found in those trunks shines as a singular jewel marking the milestones of sixty years of life in America.

When I was a child, I learned the geography of the subcontinent via her sari trunks. “This cotton sari is from the ancient city of Madurai in Tamil Nadu. I got it from a shop not too far from Meenakshi Temple so it has the blessing of Mahashakti. This Orissa silk? From Orissa State in East India. See, the border, a grid of disks along the length of the sari? It’s a reference to the nearby Sun Temple of Lord Jagannath in Orissa State.This is a Dhaka silk from Bangladesh in what was Bengal before the partition of India. This Mysore silk from down South in Karnataka? The crepe wraps like a dream. I borrowed it from my sister, but I never got the chance to return it before she passed.” Her saris, like so many textiles, persevere at the intersection of cultural heritage, artisanal genius, and personal memory. Thirty years later, as we sit on the floor of her carpeted closet, she re-tells the stories of her saris old and new and I am mesmerized in rapt attention.

Since that day on her closet floor, I’ve worn a sari to almost every fancy dress function I’ve attended. Somehow by osmosis, but mostly by watching, I’ve inherited much of my mother’s sari wrapping skills: an art form that comes with a good amount of intuition and a deep trust in the textile.

Tomorrow night as we light sparklers and apply henna to our hands, my mother’s sari will feel new and fresh, better than an off-the-rack ensemble might have when I was younger. I’ll wrap myself in the memories she made while wearing the sari, breathe in the hint of her perfume and feel gratitude for what she’s passed on as I throw the pallu over my left shoulder. Love and light to all!

Swati Argade is a founding board member of TATTER and joined the staff as Co-Executive Director in 2022. She’s worked in the fashion and textile industry as a designer, retailer and educator for over twenty years with a primary focus in heritage handmade textiles.