My grandmother’s button collection is meticulously labeled, a treasure trove of objects in tiny plastic bags or sewn onto cardstock and wrapped in brown paper. At some point during my life, perhaps when it was clear how much I loved to sew– or perhaps when I started sneaking some of her clothes home in my suitcase after long visits to her home in Massachusetts– she began to label them addressed to me. “Ella– pewter buttons from New Hampshire” reads the cracking paper on the back of a set of shank buttons stamped with stag heads, their antlers raised in hammered metal. Others are more practical: “Ann Taylor Loft Blue Cardigan” reads the tiny plastic bag with two red plastic buttons, flat with four holes.

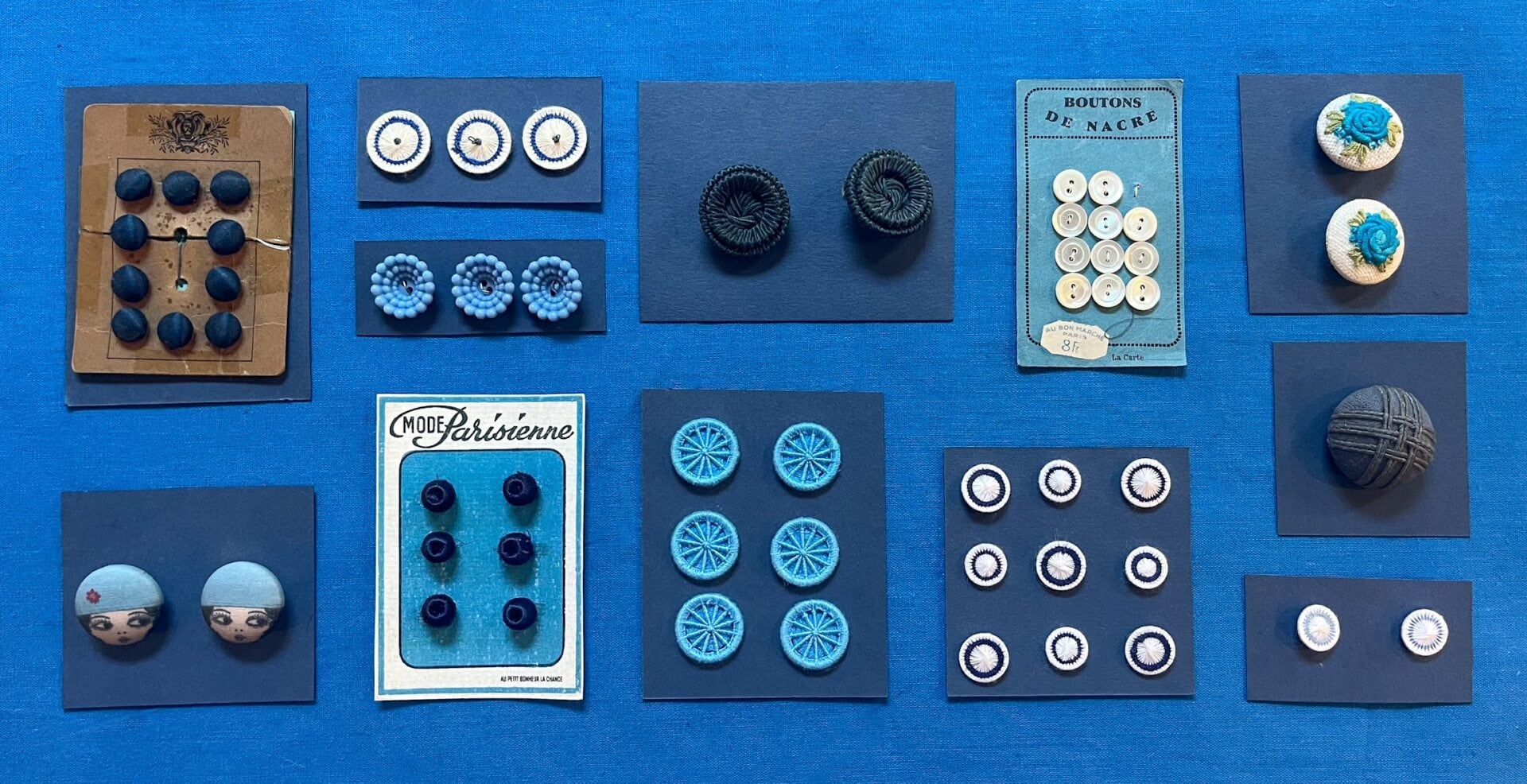

My grandmother, like many, collected buttons for practical purposes. Sewing, mending, in case of emergency. Buttons are inexpensive, they don’t take up much space, and they can be whimsical, silly, beautiful, and practical all at once. It is no surprise, then, that button collecting became popular in the United States during the 1930s. People would meet to compare collections and swap buttons, to delight over silly shapes and coo over tiny mosaic buttons inlaid with horn, ivory, tortoiseshell, and mother of pearl. In 1938, the National Button Society created a definitive system and vocabulary for classifying and collecting buttons by material, year, shape, use, and detail.

During the second world war, industries across the United States and Europe turned their production to the highly lucrative business of ammunition and supplies for soldiers fighting in Europe, North Africa, Oceana, and East Asia. Silk and nylon, once staples of women’s hosiery, became parachutes, airplane cords, ropes, and even powder bags for ammunition. Fabrics imported from countries under siege became scarce and new clothing became not only a luxury but could be seen as unpatriotic. One of the few industries that continued to grow outside of ‘the war effort’, however, was the button industry. Acrylic scraps left over from gun turrets were made into the cheap, generic buttons we see most often today. This was, of course, not the death knell for beautiful, silly, or novelty buttons. When the war ended, the fifties consumer goods boom brought back highly decorative buttons– if at a mass produced scale. Shank buttons made to look like packs of popular cigarette brands, Disney character buttons, bakelite buttons shaped like fruits and vegetables.

Of course, the history of buttons did not start in North America in the 1930s. The oldest buttons ever found were excavated in Persia, Greece, and Egypt, some estimated to be as old as four-thousand years. The prehistoric buttons look much like those we use today. Made from gold, glass, stone, earthenware, and bone, historians believe that these first buttons were used primarily for decorative purposes rather than fastening. Written records from the Zhou Dynasty in China (circa 1100 BCE) describe the use of knot buttons made with stiffened fabric and wire which remained the standard for both form and function across much of West Asia well into the modern period. By the beginning of the medieval period in Europe, West Asia, and North Africa– circa 300 CE– paintings, sculptures, and coins began to depict buttons as practical articles rather than primarily decorative. As styles moved away from draped and loose whole cloth fabrics to tailored and form fitting, buttons became a necessity rather than a luxury. Many were simply rolled or tucked fabric, stiffened to maintain shape and keep the wearer safely buttoned up without mishap.

While few buttons from this period survive, trade across the silk road began to provide access to newly inexpensive goods. These threatened to undermine the markers of class which stratified European society. As a result, much of our knowledge about buttons from this time come from sumptuary laws, restricting the use of expensive or expensive-looking materials on clothing for those who were not a part of the ruling elite. Thirteenth century French guild legislation also gives some insight into the material culture of buttons at the time: guilds for buttons were separated based on whether they utilized metal, bone, ivory, horn, glass, or earthenware.

Buttonholes also began to emerge at this time: most buttons up to this period were to be slipped through loops on the exterior of the garment and not reinforced slits in the garment itself. By the early modern period, buttons began to hit their decorative peak: in the second half of the seventeenth century, during the Qing dynasty in China, silk knot buttons took more elaborate shapes. Some were knotted or sewn into shape, others were appliqued and stuffed to give dimension and depict butterflies, flowers, or even animals. Many of these incorporated round pearl, glass, or ceramic beads which fastened the garment when slipped through the corresponding loop.

The eighteenth and nineteenth century were a golden age for buttons around the world— though not so much for many of the people who made them. Colonizers and settlers across the American and African continents brought buttons back to Europe and North America and recorded them as “newly discovered”– though of course indigenous people had been making them for centuries and possibly millenia. Beautiful and expressive polished wooden buttons from West Africa featured stylized faces and delicately carved animals. Inuit buttons, made from tusk and baleen, depicted arctic creatures including seals, whales, and walruses. These buttons were expertly carved and played with form and motion: one such button, in the Tender Buttons collection on the Upper East Side in New York City, depicts a seal’s head which, when sewn onto fabric, appears to be emerging from the ocean surface.

Buttons were also a weapon of imperialism: according to button historian Silvia Llewelyn, soldiers on foreign battlefields would often melt down the buttons on their uniforms to recast them into bullets. While today the loss of a button or two could compromise the wearability of a garment, European and Ottoman clothing in the eighteenth century arguably had too many buttons. An English man’s waistcoat alone had a minimum of a dozen buttons, often more for decorative purposes. To distinguish simple functional buttons from those reserved for people of high status, button design and materials became increasingly more creative. Buttons were covered in rich fabrics, embroidered with metal threads and decorated with paste jewels, or commissioned in a series of paintings to tell a visual story which could be read across the garment. Others, from semi precious stone, were gilded and decorated with precious metal foils. The particularly stunning “habitat button” consisted of a metal shank painted and then decorated with shells and foliage behind glass. Porcelain, jasperware, enamel, silk, and mother of pearl joined wood, ivory, metal, and earthenware as common button materials. Industrialization and globalization in the 19th century brought innovations in button technology that have since tragically fallen out of fashion. Tintype photography allowed people to buy buttons printed with the images of their loved ones, eventually expanding to create campaign buttons printed with the images of political candidates.

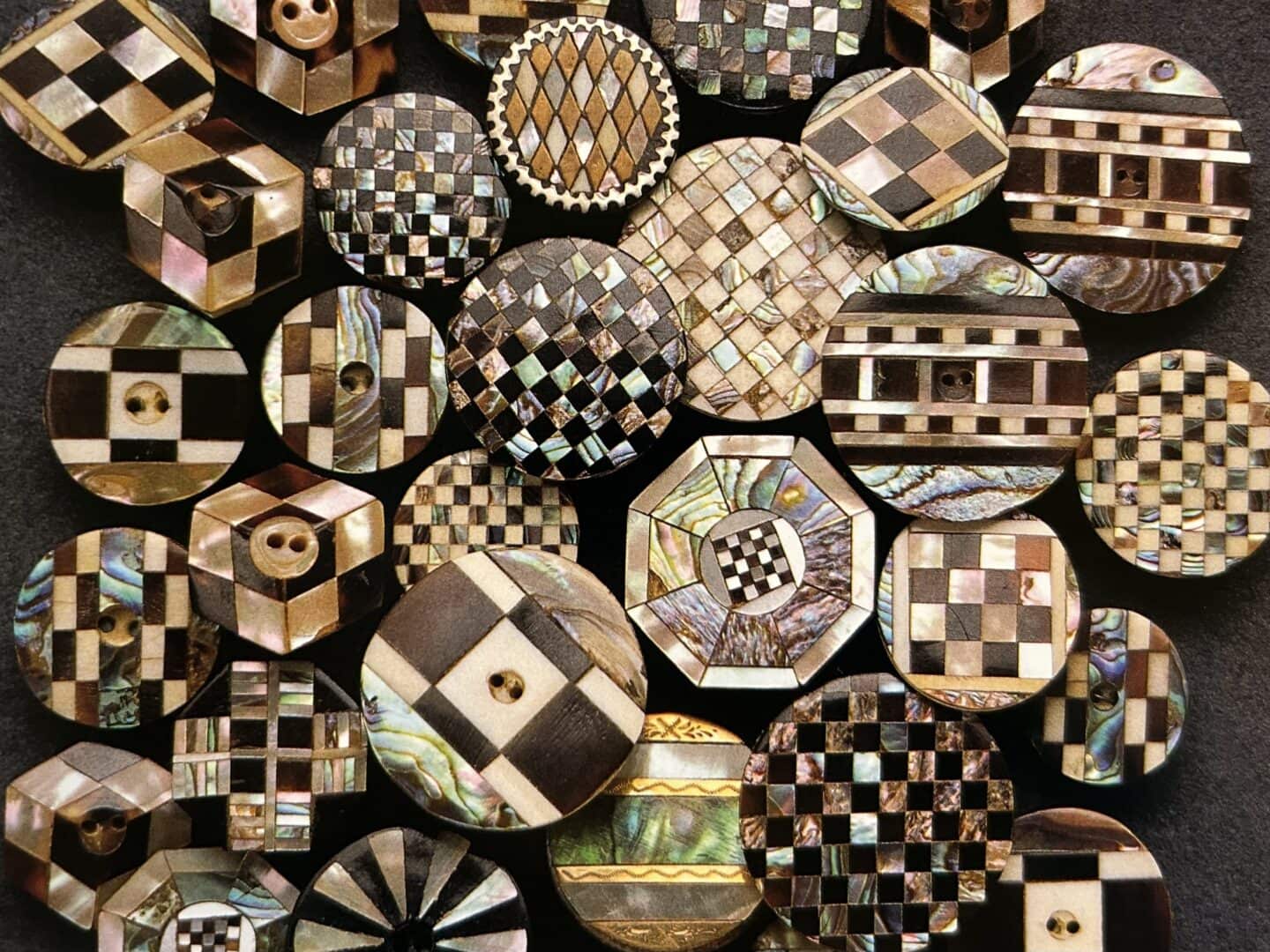

Global movement of goods and people also led to changing aesthetics: European incursions into Japan created a growing market for enamel and gilded pieces with traditional Japanese designs. Though most Japanese people continued to prefer traditional knot buttons for their own clothing, Japanese artisans began to create beautiful buttons for European markets from enamel, metal, ivory, satsuma ware, and pottery. As the Japanese elite began to adopt more “western” clothing styles, these buttons created a tie between Japanese aesthetics and western clothing both in the west and in Japan. The Arts and Crafts art movement of the late nineteenth century also made its contributions to button styles, namely through dramatic and beautiful geometric inlay buttons decorated with thin veneers of abalone shell, tortoiseshell, ivory, and horn. While you would be hard pressed to find such delicate and intricate work on such a small part of a garment made today, at the end of the nineteenth century the average person owned only a few sets of clothing.

A new set of buttons could refresh an old garment and allow the wearer to follow trends in design and art movements without having to create or commission an entirely new wardrobe. It was also around this time that clothing manufacturers began to create ready made clothing for children. While most of the clothing essentially replicated adult styles, buttons depicting scenes from fairy tales and popular children’s stories added a sweet and whimsical touch.

It was also during this period, mass produced abalone shell, glass, and plastic buttons brought to the north western United States by European settlers were adopted as decoration by indigenous people. Ceremonial blankets, originally made from cedar bark or dog fur, became more typically created from wool or flannel. Designs on the blankets represented identity, status, and heritage. Today, button blankets remain an important part of the artistic practice of the Kwakwaka’wakw people and other indigenous groups in the northwest. Artists combine geometric and representational shapes surrounded by buttons which reflect and catch the light when worn on the body. These artists prefer small, plain, shiny buttons which highlight the bold colors and shapes of the appliquéd designs.

While some distinct buttons remained popular, the beginning of the twentieth century largely spelled an end of the market for expensive artisanal buttons. Amidst the brief period between the First World War and the Great Depression, Bakelite buttons with angular art deco motifs and novelty silk buttons painted to look like the sly sweet faces of fashionable women became popular for evening wear. Still, as more and more people bought ready to wear clothing rather than homemade or tailored, the plain cheap plastic or shell buttons most familiar to us today began to overtake their more elaborate predecessors. While the zipper was invented in the late 19th century, it wasn’t until the 1930s that they became commercially available to the general public. The zipper made it much easier for people to dress themselves and quickly overtook the humble button, making it more generic, less gendered, and certainly less detailed.

Still, buttons haven’t been entirely consigned to the quaint or antique. Buttons are still functional accessories to garments, and therefore companions to people. Like all sartorial portraiture, they tell stories of migration, imperialism, fashion and our relationships to currency, trade, and shared material culture. On this National Button Day we acknowledge not just the innovation, but the historical weight that it carries: how one tiny thing we use every day comes to us from thousands of years ago across trade routes along which we still traverse.

I love to look at my grandmother’s buttons, especially on days I miss her most. I keep them in a pickle jar on my sewing desk and while I cannot yet bear to break up the collection for mending, it comforts me with its promise that I can take the things I love that do not work for me and make them something new. A few buttons remain separate in her jewelry box, where I found them strung on a fraying cotton cord. My grandmother had kept this little necklace next to her elegant jewelry, a reminder of the day the two of us had gone through her collection and picked our favorites out from the jumbled lot. My tiny fingers had fumblingly threaded them together and presented them back to her. I had treasured these buttons so much that I wanted her to have them, to give her something precious because she was precious to me. These everyday things with which we clothe ourselves are more than form or function: they have stories to tell, if we take a moment to listen. They are history, they are memory, and they are love.

FURTHER READING AT TATTER

Beaman, Sarah. The Button Maker: 30 Great Techniques and 35 Stylish Projects. Collins & Brown, 2006.

Epstein, Diana, Safro, Millicent Buttons Harry N. Abrams Inc. New York, New York. 1991

Meng, Kaari, and Jon Zabala. French General: Treasured Notions: Inspiration and Craft Projects Using Vintage Beads, Buttons, Ribbons, and Trim from Tinsel Trading Company. Chronicle Books LLC, 2013.

Peacock, Primrose, and Rosemary Godsell. Discovering Old Buttons. Vol. 213, C. I. Thomas & Sons, 1984.

REFERENCES AND PHOTOGRAPHS:

Button Blanket. Denver Art Museum, University of Denver Morgridge College of Education, Denver, CO.

Dauterman, Carl Christian. Buttons in the Collection of the Cooper-Hewitt Museum. Cooper-Hewitt Museum; 1 Jan. 1982.

Epstein, Diana, Safro, Millicent Buttons Harry N. Abrams Inc. New York, New York. 1991

Ling. The Ultimate Guide to Cheongsam Button – Pan Kou – Newhanfu. Hanfu Forum & Community, 13 Mar. 2023l.

Sundin, Sarah. Make It Do – Stocking Shortages in World War II. Drama, Daring, Romance, 7 Aug. 2021.

Chinese Knot Button. China Culture, Classics, Art