Part of the mission of TATTER and its corresponding library, BLUE, is to celebrate the unique relationship we have to cloth. At BLUE, we feel that each book in our collection is a gift. Each volume, periodical, or exhibition catalog is a unique contribution to the continually developing conversation of fabric – and the evolving roles it plays in our lives.

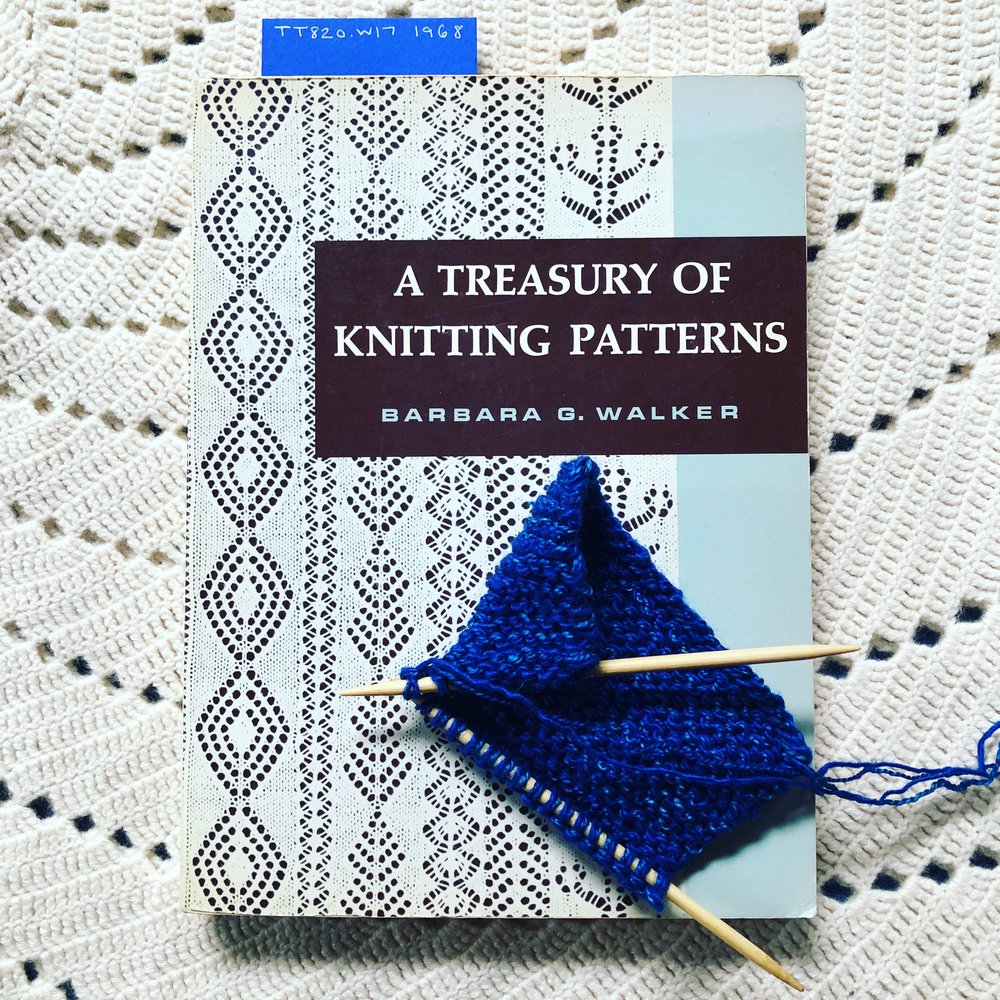

Late last spring I was dreaming of a way to come together as a community and highlight the importance of these books. I thought of the Barbara Walker Treasuries. So iconic. Still so relevant. In the late 1960’s Barbara Walker, a journalist and author of many non-knitting related books, compiled and published one of the first knitting stitch dictionaries. Comprised of hundreds of patterns – some with historical references – Walker’s A Treasury of Knitting Patterns remains one of the most comprehensive and pioneering how-to bibles of knitting. Walker went on to publish three more treasuries! They are still in print, still marvels, and grace so many of the bookshelves of today’s knitters, continuing to educate and inspire. Generations of artists and designers credit Walker with the inspiration for their own creations.

What does it mean to have added so much to the global conversation of knitting? How does one quantify a legacy like this?

BLUE is not just a library of books and printed matter. It is also home to objects, swatches and garments. These material artifacts are the evidence of our historical cloth conversation. They make the print on the pages come alive. Many of us knitters have held or thumbed through Walker’s treasuries, our minds filling in the tactile blanks of hundreds of black and white swatch photos. I myself have long wanted to see these images at least in color – if not outright desired to slide my fingertips across the actual bobbles and cables.

I think this is how the project came to be. Part homage to Barbara’s legacy, part endless desire for textile community, part educationally driven, and part curiosity about others who share my love of knitting and these incredible volumes of stitches, I embarked on the community-sourced crusade of knitting a BLUE version of Walker’s first treasury.

I made a simple (and naive!) request on social media. Hey Knitters! I casually announced, We’re knitting BW’s first Treasury. Direct message me if you want to contribute! Of course I had no idea what I was getting into, and no imagining of what the project would come to mean.

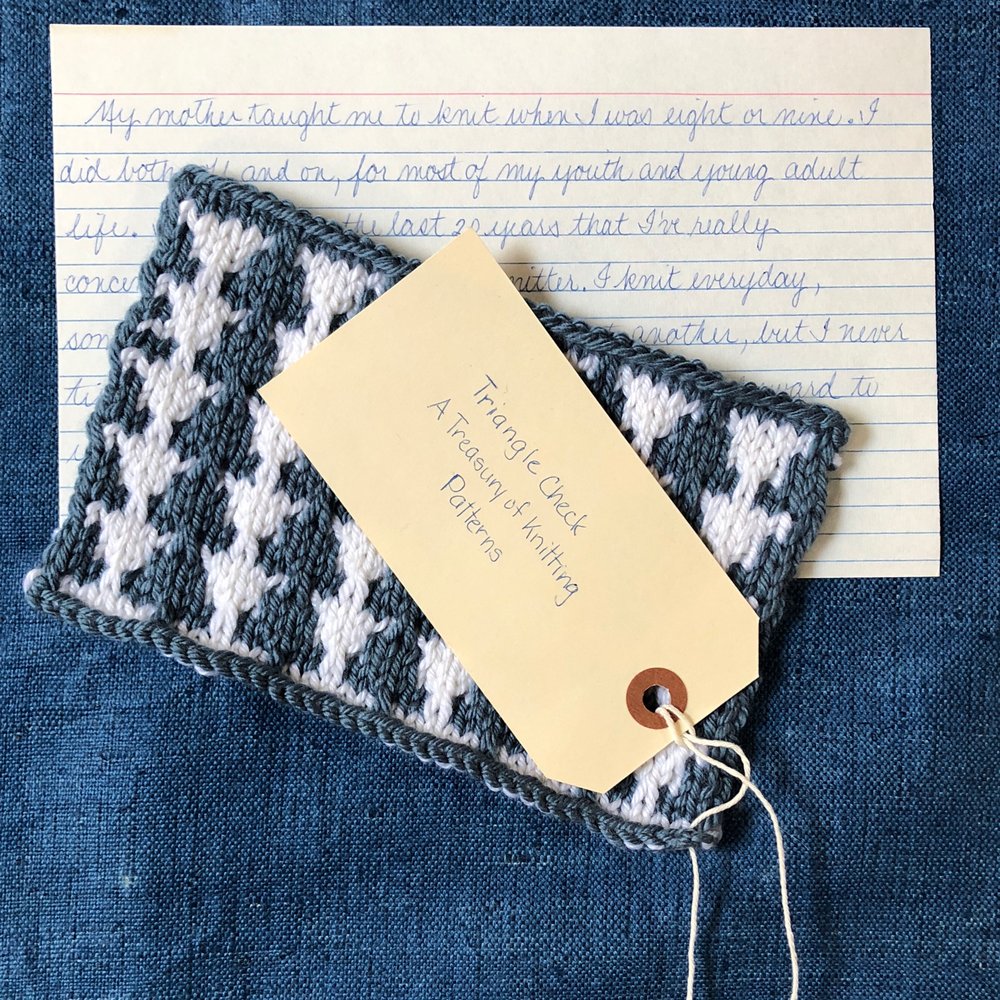

Knitters worldwide reached out. We gave them directions. Loosely: knit your assigned swatch, in any blue fiber you wish, in roughly a specific dimension. But also this: tell us where you are from, when you learned to knit, what knitting means to you, what BW and her treasuries mean to you.

And then the swatches began to arrive in the mail. Each one was beautiful, and like a love letter - an unexpected nugget of true humanity, the antidote to the news! How wonderful.

Before I knew it we grew to 400 knitters from 14 countries. And in addition to hundreds of swatches, we have hundreds of stories. What knitting means to you. What BW means to you. What knitting, across our planet, means – to all of us.

This has certainly been a wonderful project. I send my most HEARTFELT GRATITUDE to each person who contributed their time, their craft, and shared a bit of their life. The very last swatches are rolling in. We have the most amazing blue version of Barbara’s first treasury, and as my fingers slide across the bobbles and cables, across the eyelets and ribs and tucks, I say – COME AND SEE. Come to the library and experience this marvelous thing.

Knitted swatches from Chapter 4. Photo: Rochelle Voyles

Knitted swatches from Chapter 2. Photo: Rochelle Voyles