The making of an indigo dye vat is a process of sacred chemistry. Every step of the process, from the cultivation of the plant, the gathering of the leaves, and the tending of the bacteria is the work of many skilled hands and centuries of knowledge. Combining indigo and mud is more than a technical process; it is an alchemical act that marries the celestial qualities of indigo with the grounding properties of earth. For Malian dyers, this synthesis reflects the Malian worldview of harmonizing opposing elements to create balance and beauty. Dating back to at least the 10th century, the use of indigo dye in Malian culture represents a connection to the natural world and the cosmos, symbolizing depth and infinity. Once an essential element of Malian culture and cosmology, the process of creating dye using only whole indigo leaves, lye from ash, a fermenting agent like tamarind pulp, crushed date powder, or honey, and cereal bran was almost entirely eradicated under colonial occupation. Malian and French dyer Aboubakar Fofana has dedicated his life to restoring the ancestral knowledge and teaching the practice of traditional indigo dyeing on the African continent.

“Indigo in Mali almost completely died out after Western colonisation,” Fofana told TATTER for Beyond Blueness in the TATTER Journal issue three, Blue. “The French requisitioned and broke our economy and stole control of the cotton trade from our growers, spinners, and weavers, forcing them to produce white, long-staple cotton and leaving our many species of coloured cottons to disappear. Our complex indigo-dyeing techniques were discarded and broken, too. They could not be easily reproduced, scaled-up, transported – they could not be exploited. And as the hand-spinners and weavers of our sacred cottons disappeared; our indigo dyers themselves passed into memory. By the time I was born, the knowledge was already lost.”

Classical Malian dyers could achieve twelve shades of indigo, ranging from the lightest kiss of blue, Bagafu, the blue of nothingness, to lomassa dunné, the blue of the profound divine sky.

“In my work, the first shade I can create is not my creation at all. It is the raw fibre before it is dyed. All of the shades that I create can only be gradated by reference to the undyed cloth,” said Fofana, “our perception of all colours is altered by the colours around them, even when they are essentially shades of the same colour. The medium-dark shades I can create may look dark on their own until they are compared to the darkest shade of all, lomassa dunné.”

So blue that it becomes black, lomassa dunné embodies notions of maturity, wisdom, and the unknown. It represents a journey into deeper understanding and the mysteries of existence. Similar to the various shades of indigo symbolizing different states of consciousness, black in Malian culture can signify a profound connection to the ancestral and spiritual realms. This is achieved by mixing earthen mud with the fermenting leaves, not only imparting color but also embedding the fabric with the essence of the earth, symbolizing a tangible link between the wearer and the land. In Mali, black dye holds significant cultural importance when used to create a traditional textile known as bògòlanfini, or mud cloth. Hunters wore bògòlanfini for camouflage and as a form of ritual protection, with the black dye symbolizing strength and resilience. Women donned mud cloth during significant life events, such as after childbirth, believing the fabric had the power to absorb dangerous forces released during these times.

“In Bamanankan, the name mà ngálábá yírí translates as ‘the Creator’. The same word holds the root of the name for indigo-dyed cloth and for indigo pigment – gálá. Indigo plants are known as gálá yírí, which translates as Divine Tree,” explained Fofana. “Indigo dyeing as practiced in West Africa was always deeply spiritual, and our language shows our link to indigo as divine, as deep and as old as our link to our own humanity. Still, regularly, in books I see no mention – or only a passing mention – of African indigo. Often it is called ‘Yoruba Indigo’, which deftly attributes indigo to a single cultural group inside a single country rather than associating it with hundreds of cultural groups across many countries – a reduction as colonial as the word indigo itself.”

Last summer, Fofana came to TATTER to teach Malian stitch resist and shades of indigo dye at the Pratt Institute dye garden. This June, he will return for an inaugural Black Dye Workshop, providing a rare opportunity to learn to achieve this elusive color while exploring an ancient Malian tradition steeped in spiritual cosmology. In this immersive three-day long workshop, Fofana will be unveiling his techniques that harmonize the vibrant essence of indigo with the rich, earthy character of mud from the Niger River in Mali. His approach is not merely about dyeing fabric—it is a profound cultural exchange that invites students to explore the alchemy of nature and tradition. Throughout the workshop, Fofana will allow students to experience firsthand the meticulous process of transforming indigo and mud into shades of grey and the deepest, most soulful, blacks.

Sign up today to join us as we journey through shades of indigo to arrive at that most potent of blues, lomassa dunné, and learn the ritualistic aspects of the process underscore the importance of balance, patience, and respect for the environment. You can read more about Fofana and his work in the Journal and in his book, Terre et Feuilles, in the TATTER library collection.

Learn Black Dye with Aboubakar Fofana at TATTER

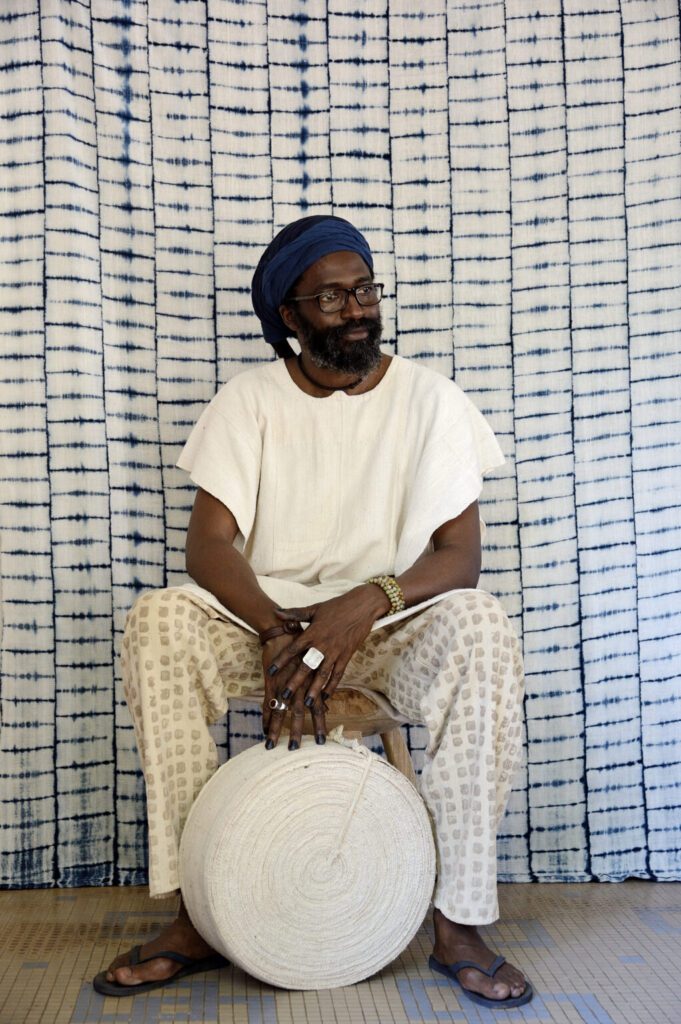

OUR TEACHER

Born in Mali and raised in France, Aboubakar Fofana is a multidisciplinary artist and designer whose working mediums include calligraphy, textiles and natural dyes. He is known for his work in reinvigorating and redefining West African indigo dyeing techniques, and much of his focus is devoted to the preservation and reinterpretation of traditional West African textile and natural dyeing techniques and materials.

Fofana’s work stems from a profound spiritual belief that nature is divine and that through respecting this divinity we can understand the immense and sacred universe. His raw materials come from the natural world, and his working practice revolves around the cycles of nature, the themes of birth, decay and change, and the impermanence of these materials. He sees the conception and realisation of this work as a form of spiritual practice which is shared with his audience.

Fofana is currently deeply involved in creating a farm in conjunction with the local community in the district of Siby, Mali, in which the two types of indigenous West African indigo will be the centerpiece for a permaculture model based around local food, medicine and dye plants. This project hopes to contribute to the rebirth of fermented indigo dyeing in Mali and beyond, and represents his life’s greatest project to date.