Sarah Woodyard is a textile artist and historian dedicated to studying dressmakers of centuries past. Her upcoming class for Tatter, “Historical Hand-Sewn Shirt,” teaches students how to craft a traditional nineteenth-century shirt. Tatter recently spoke with Sarah to learn more about the shirt in her collection that is the archetype of this garment tradition, its connections to modern-day fashion design, and what one can learn from historic textiles.

What was the historic teaching process for sewing these shirts (i.e., generational, workshop, etc.)?

Shirts were made by seamstresses, and being a seamstress is a skill that would be taught in a couple of different ways. Some individuals were seamstresses as their job (paid and enslaved work) and they may learn that skill through an apprenticeship model where somebody teaches them how to do it, who is not related to them. Some people did seamstress work as a form of unpaid housework, and in those cases, a family member may pass on the skillset to them. Prior to the late eighteenth century in a European context, there weren’t a lot of written instructions on how to make these things, so it was a skill taught through observation and personal practice.

How was this style communicated and shared over time and across geographical boundaries?

Letters, newspapers, magazines, and using the actual shirt as design inspiration.

What were the different ways in which this shirt was worn and styled?

The shirt can be styled in so many different ways. As a modern garment, it can be worn as an upper body garment, or it can be worn in a tunic style or more like a dress style.

Historically in the U.S., it was worn as a garment next to the skin tucked into lower body garments with waistcoats, and coats over top of it. It was intended to absorb oils, dirt, and perspiration, and be a barrier between clothes and the body. It was underwear and it would be changed at least once a day to keep the body and outer clothes clean. It was also used to cool the body on hot days. in very hot climates, like Virginia or the Caribbean, you would see individuals sometimes just wearing a shirt.

Native men and some women on the east coast such as Mattaponi, Pamunkey, Shawnee, and Cherokee people did not wear the shirt in the same way. They would typically wear a shirt as an outer garment with a breechclout or a wrap shirt on the lower body, or worn under different styles of coats, wrappers, and mantles. The shirts were sometimes made shorter and out of different materials to represent their culture and fashion.

Is the ubiquity of this type of shirt unique or are there other examples with similar universality?

While some of the design details situate this style as a European design, rectangular, hand-sewn shirts/tunics cut out of squares, rectangles, and triangles are ubiquitous across the globe. The shirt has cousins in India, the Middle East, Japan, and West Africa, and likely has its roots in the rectangular shirts/tunics of these regions. Geometric forms to minimize textile waste. When fabric is an expensive item, being careful with cutting is a universal experience. This cutting theory is a deeply rooted historic practice across the globe.

Furthermore, hand-stitching is also a global and universal experience. There are similarities to the type of stitches that are used to stitch clothing together across place and time.

What can contemporary clothing makers learn from the historic shirt?

They can learn about the lineage of where styles have come from, and gather rich design inspiration from the cut in the construction and the textile choices of historical makers. I personally believe that hand-sewn garments are a thing of beauty and skill. It’s an opportunity for contemporary makers to learn about the value of cultivating a level of skill in their own clothing-making process and applying this to modern clothing.

The historical shirt was cut out at a time when fabric was expensive and so the maker utilized minimal waste efforts, today called zero waste, to cut out rectangles and squares to use the most fabric possible. For example, in the shirt, the entire width of the fabric goes from the shoulder down to the hemline. Contemporary clothing makers can learn to think of layout differently, and how to use the width of the modern fabric in a way that minimizes waste.

The shirt is 100% hand stitched, and the goal of this project is to really immerse the maker in the hand-sewing process. Hand-sewing construction is very efficient and it is very fluid. I hope that contemporary makers when studying a historical garment and then re-creating the stitches will learn that there is efficiency and speed to their hands when stitching it together.

If a contemporary maker has only used a sewing machine, it can be easy to look at hand sewing and think that it is either impossible or extremely time-consuming. However, when you actually go through the process of learning to hand sew through practice you learn how fast and how effective hand sewing can be when applied correctly.

What are the physical aspects of a textile that you look for to tell the story of its wearer?

Well, the design of the garment can give you a sense of the geography of where that individual might have roamed during a particular time in history. The quality of the textile can give you a sense of what the garment was worn for. Without knowing more about the person’s life, it can be tricky to point to what their socioeconomic status was because some working-class individuals dressed very nicely, and some wealthy individuals had work clothes. The style can reflect gender identity. Of course, looking at the size of the garment can give us a sense of age. You also get a sense of their body height, and sometimes their build. And to get kind of gross, sometimes there are physical remnants of the body. Sometimes there’s sweat on the clothes, sometimes there’s blood on the clothes.

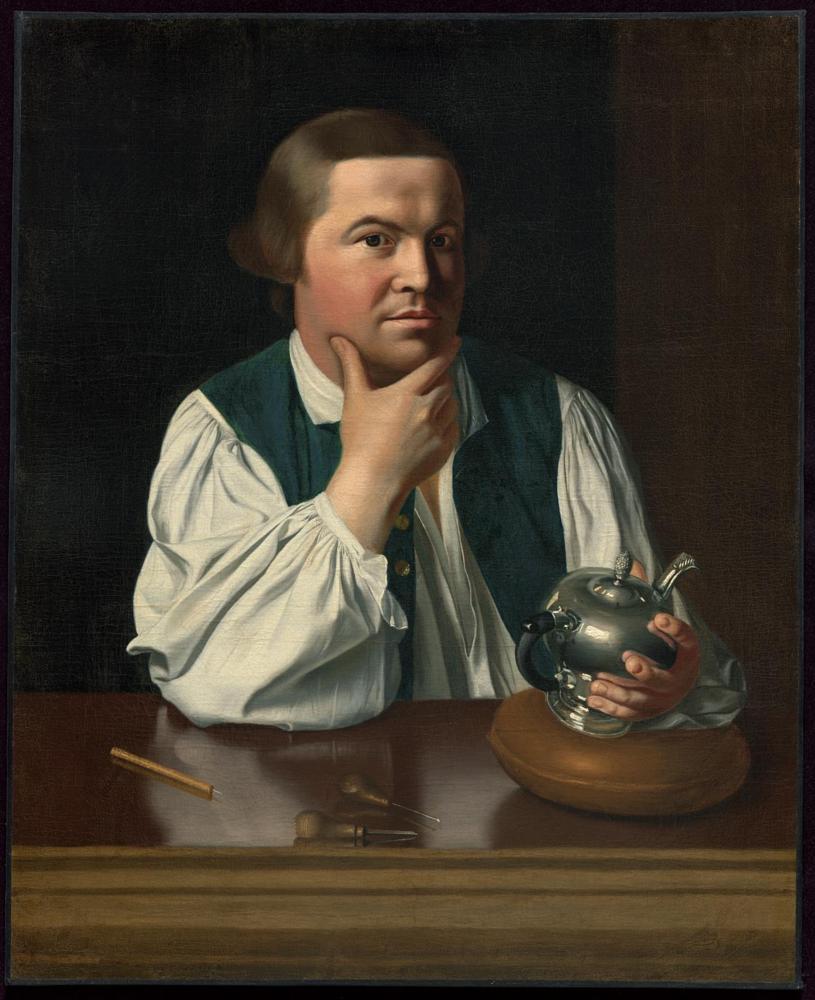

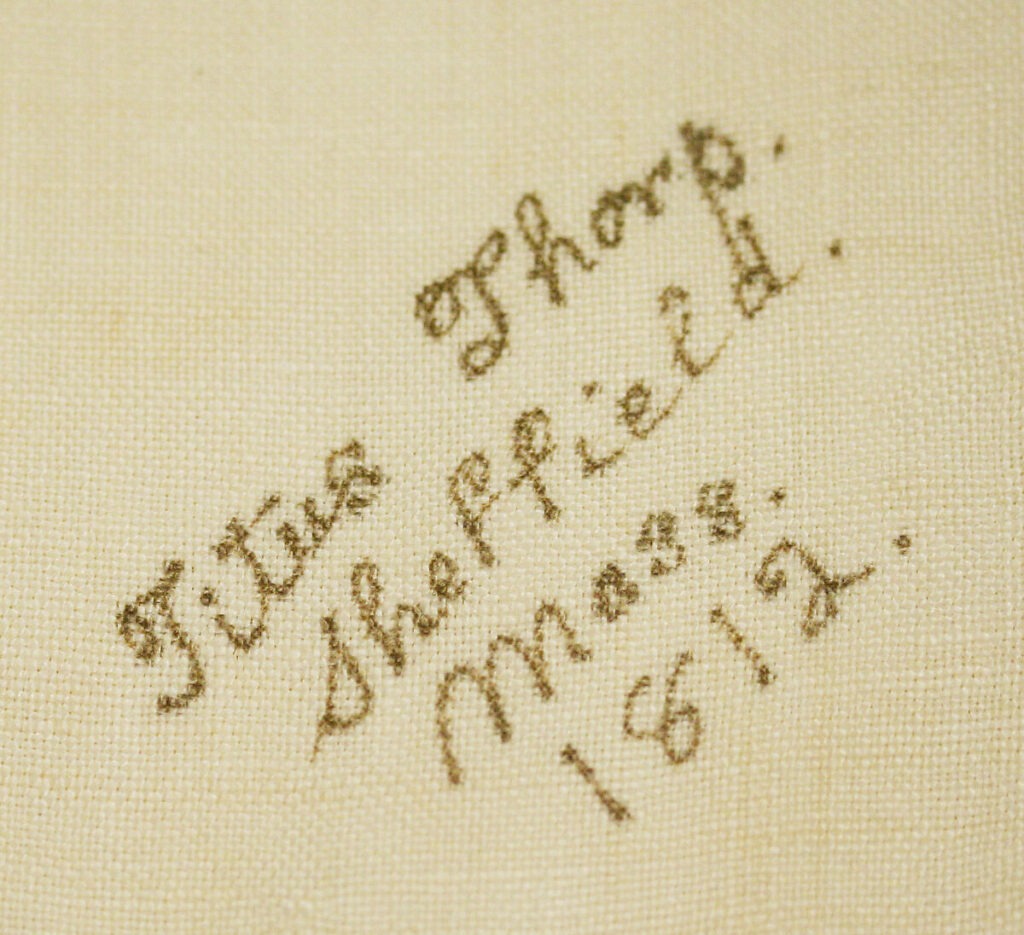

Sometimes there’s writing on the clothing—people would write their name on their garments, or put some sort of marking to denote that it is their clothing. For example, shirts have a marking on them. The shirt that we will be making has cross-stitched marked initials at the front of the shirt. This laundry mark would help to organize your shirt from the other shirts that are being washed at the same time, as well as the other shirts that might be worn in the household that you live in, so marking your clothing was exceedingly common at a time and place when these shirts are so ubiquitous in style that sometimes a mark and a number is the best way to keep track of it.

What can be learned from physically recreating a historic textile?

Hand-sewing an entire garment with needle and thread is possible.

One of the first things that come to mind is skill. Studying the skillful hand of a historical seamstress and re-creating it is a way to cultivate a deep skill. Cultivating that skill is a wonderful way to show how much you can do with your body, and how skillful humans can really be through practice. That deep skill is both embodied, but also opens up a depth of history and connection to the lineage of seamstresses who stitched across the globe for more than 30,000 years. It could be a connection to a personal family member, a friend, or a colleague. Or it could be an embodied kind of spiritual connection to someone from the past that you’ve never met, but you’re going through a similar experience that they did and so there is an inherent link between you and that individual. When we sit and we stitch, we contemplate stitchers who work in the fashion industry. Historically it allows us to be empathetic about their experiences, and I believe it also allows empathy for modern stitchers and individuals in the sewing industries.

In a very practical sense, you physically learn how to cut out the shapes of a shirt and understand the proportions and the sizing of a shirt and you learn how to sew certain seams and hems. you learn how to do beautiful topstitching on cuffs and collars. Some of my favorite techniques that I am excited to pass on with this shirt are the top stitching on the cuff, teaching people how to sew quickly and efficiently, and doing hand-stitched buttonholes.

I want people to feel a sense of pride for what they are capable of stitching and a connection to a long lineage of skillful stitchers that came before us. By recreating this shirt we are preserving these skills.

Sarah Woodyard will be teaching Historical Hand-Sewn Shirt on Fridays, April 14th, 21st, 28th, May 5th, and 19th!

Sarah Woodyard is inspired by the labor of historical dressmakers. She spent seven years apprenticing at the Margaret Hunter Millinery Shop in Colonial Williamsburg to learn eighteenth-century mantua-making (dressmaking) and millinery (accessories). After completing her apprenticeship she became a Journeywoman mantua-maker and milliner. Sarah holds her M.A. in Material Culture from the University of Alberta. After ten years of sewing and interpreting at the Margaret Hunter Shop it was time to take this knowledge into the twenty-first century. She opened Sewn Company in 2019. Through Sewn she teaches historical hand-sewing to historical sewists and modern makers. She is passionate about preserving the skills and stories of hand sewing, through research, design and education. www.sewncompany.com