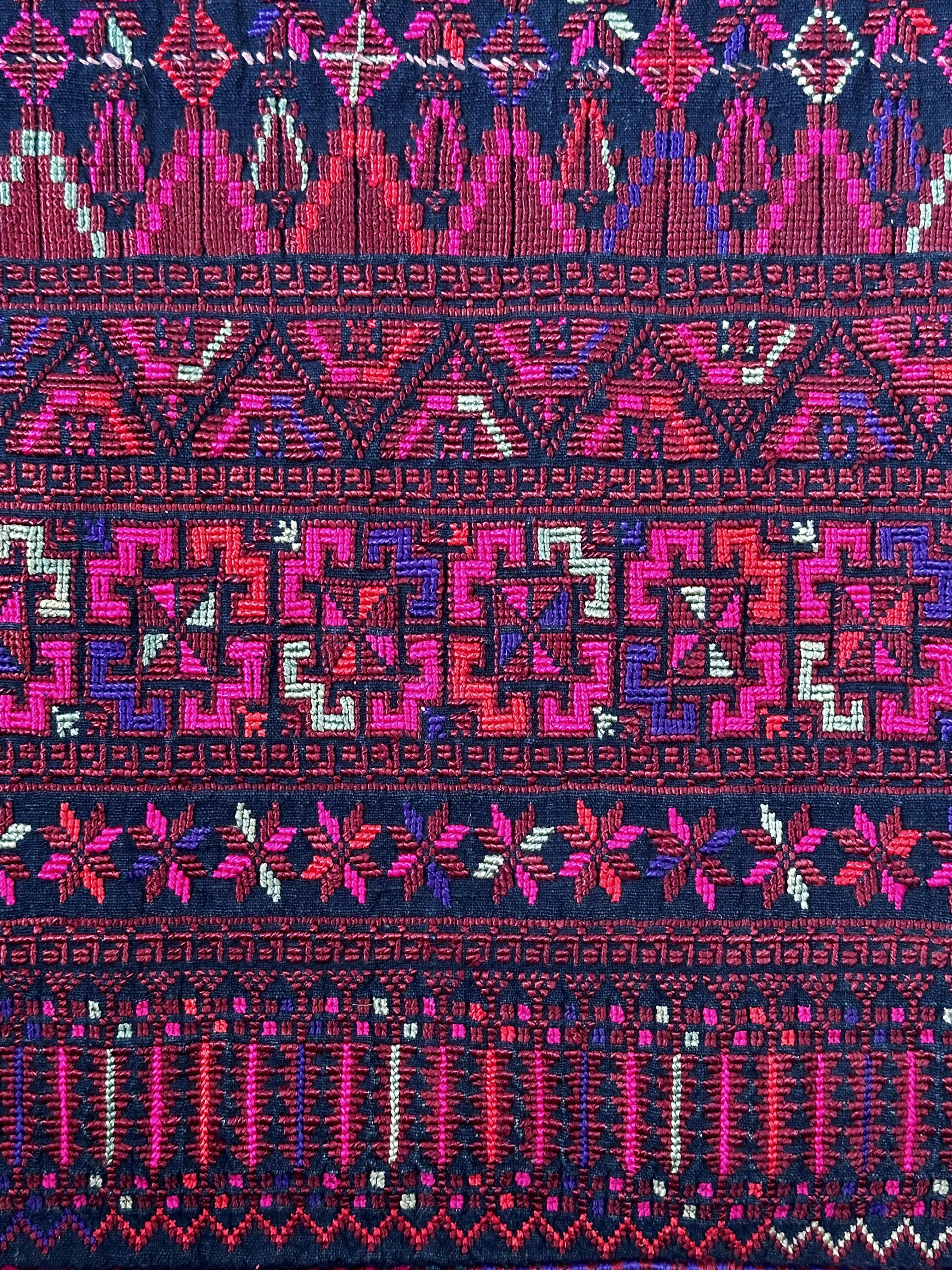

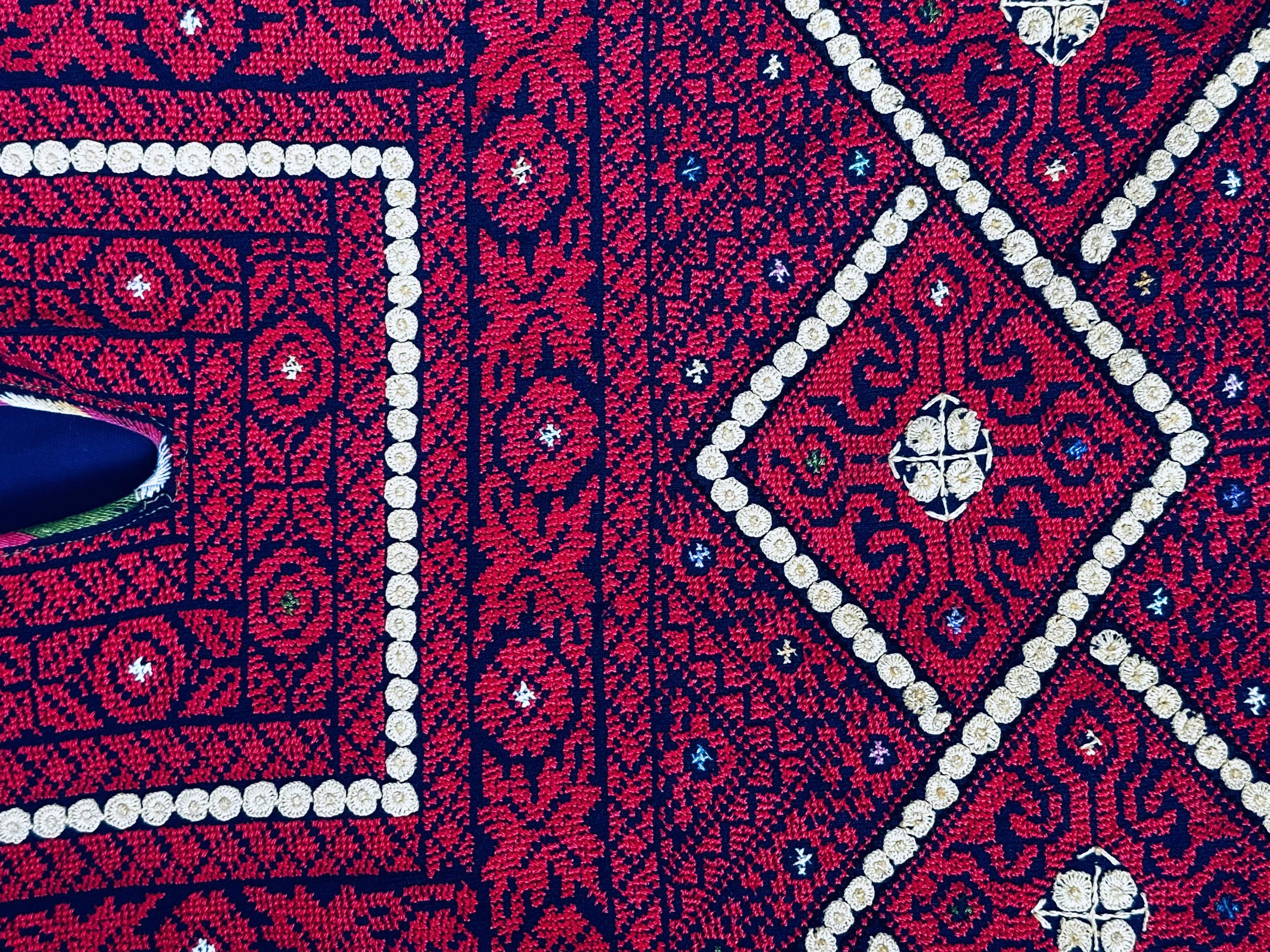

In the years after 1948, and again in 1967, beautiful and intricately embroidered Palestinian dresses, or thobes, flooded the international antiques markets. Some thobes as old as the mid 19th century were made from lengths of handwoven linen, cut with a square or rectangular chest panel and sleeves which either fanned out or subtly tucked in at the wrist. All of the dresses were ornamented with silk threads, embroidery (or tatreez in Arabic) that included cross-stitch, with a collection of motifs and designs unique to Palestine. The dresses were a testament to the survival and the desperation of their makers following the wars of 1948 and 1967, known as Al Nakba and Al Naksa respectively. Al Nakba translates to ‘the Catastrophe’ in Arabic; Al Naksa means ‘the Setback’ or ‘the Relapse’. This is the story of those dresses, the people who made them, and the people who make them still today.

There is a widely held misconception that there is a single and static type of Palestinian dress or embroidery exclusively practiced in a specific region of historic Palestine. Some motifs do draw their origins from ancient communities: the Bethlehem chest piece, for example, features four branches twisting out of a jug to depict the tree of life. Like many traditions, however, tatreez is a living art form that has been practiced over centuries. Motifs, techniques, and their meanings are continually expanded by Palestinian embroiderers who live in diaspora, refugee camps, and under military occupation. New dresses draw inspiration from old; daughters copy the patterns stitched by their mothers and grandmothers, their careful hands tracing over old paths and remaking them anew. Many dresses throughout time have been embellished with panels cut from older textiles, recycling the older handiwork to reflect new dress styles or replace tattered garments while preserving traditional designs. Held together with new cloth, these panels speak of Palestinian resistance to cultural erasure. Thobes are memories, and the work to preserve them is never ending.

While the practice of tatreez stretches back through ancient history, an abundance of tiraz fragments from the Mamluk Era (13th to 16th century) survive in collections such as the Ashmolean Museum and The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Even under Mamluk Empire rule, the creation of embroidered dresses was rooted deeply in the land. Threads imported from Egypt and Syria were sold to Palestinian artisans who in turn hand-wove bolts of fabric. These bolts were then most often dyed with indigo grown by Palestinian farmers south of the sea of Galilee. While the majority of silk came from present day Syria, spinners in Palestine had cultivated mulberry trees from the sixth to nineteenth centuries to feed silkworms. Silk spinners and purchasers of raw silk dyed their threads with locally grown plants; red, the most popular color used in traditional Palestinian embroidery, was most commonly colored with organic material such as madder, kermes, and cochineal.

The majority of textile production in Palestine leading up to the nineteenth century was done on a small scale by local weavers, primarily men, on looms based in their own homes. Because of their connections to Egypt, by the beginning of the twentieth century Al-Majdal in the historic Gaza region had been established as the center of the Palestinian textile industry. Palestinian factories and cottage industries both locally grew and imported raw materials from around the world to produce hand woven and machine loomed linen, cotton, wool, and silk fabric. Oral history records indicate that before 1948 every home in Al Majdal had a loom. In 1946, Khalil Oweida opened El Manar textile factory in Gaza, catering to the growing city and outlying towns. It was completely destroyed only two years later.

In 1945, Gaza’s population was estimated to be around 18,000. After Al Nakba, more than 200,000 of the 750,000 refugees from historic Palestine were resettled in eight tightly packed refugee camps across the Gaza Strip. In August of 2023, there were an estimated 2.2 million people living in Gaza, more than eighty percent of whom were registered as refugees. At only 140 square miles, the Gaza Strip is one of the most densely populated places on earth.

In the early 1950s, refugees from Al-Majdal set up new weaving shops across the Gaza strip, providing a desperately needed source of income for refugees. Embroidery cooperatives in Ramallah and Jerusalem also provided work for displaced women and girls who began to incorporate new techniques and patterns into the traditional practice. Brilliant flowers and crowing birds stitched their way across cotton, linen, and velvet canvases. Many of these landed in the personal collections of tourists who moved freely through the borders that kept internally displaced Palestinians in and their families in diaspora out.

According to dress historian and tatreez artist Wafa Ghnaim, most refugees who left their dresses in their homes during Al Nakba expected to return. Settlers and immigrants either kept the dresses, donated them to thrift stores, or sold them to tourists and antiques dealers. Within a few years after Al Nakba, those refugee women who had fled their homes carrying their most precious dresses ended up being forced to sell the garments for desperately low sums. In 1952, the American Quaker Rolla Foley purchased a beaded and embroidered wedding dress from a refugee woman in the Occupied West Bank. Originally from Al Tireh, the woman and her husband had fled their home with only a few prized possessions during Al Nakba. Four years later, under financial duress, she sold Foley the dress. She had sewn and decorated the dress with her own hands in anticipation of her wedding day and kept it afterwards as a reminder of the life she had imagined for herself before she was displaced. He paid her only seven Jordanian dinars.

Following Al Naksa 1967, an estimated three to four hundred thousand more Palestinians were forcibly expelled from their homes. Once again, a wave of Palestinian dresses ended up on the global antiques market. According to dress historian Wafa Ghnaim, acquisition records show that a significant portion of the embroidered Palestinian garments housed in the British Museum collections were donated after Al Naksa. In her book Thobna: Reclaiming Palestinian Dresses in the Diaspora, Ghnaim writes that the first historic thobe she acquired in her personal collection was from an American woman who had been working in Jerusalem during the 1967 Al Naksa. In the following days after the war, the woman purchased the dress from a Palestinian woman seeking income in the city. It is beautiful, with belled sleeves, handwoven silk, and intricate embroidery and applique from Al Khalil. The American woman purchased it for five dollars.

Over the past seven decades, Palestinian women have continued to preserve, expand, and teach the art of tatreez. It remains a cottage industry in the occupied Gaza and West Bank where refugee women continue to embroider to sustain their families and their culture. Those in diaspora, too, continue to teach their children how to stitch ancient motifs into new fabrics. The people of Gaza, once again forced from their homes, are fighting to protect each other, to speak to the outside world, to survive. Dresses grown, spun, woven, cut, and embroidered in the land of Palestine make their way around the world across eras and borders. Their bright colors are the evidence of enduring culture: the work of many hands and of makers once known. Through embroidery, their voices continue to be heard. When we stitch tatreez, we join our hands to theirs.

REFERENCES

Abu, Omar Abed Al-Samih. Traditional Palestinian Embroidery and Jewelry. Al-Shark Arab Press, 1987.

Crisis in Gaza. United Nations Population Fund, updated 31st October, 2023 www.unfpa.org/crisis-gaza.

Ghnaim, Wafa. Thobna: Reclaiming Palestinian Dresses in the Diaspora. The Tatreez Institute, 2023.

Ghnaim, Wafa, Safa Ghnaim, and Feryal Abbasi-Ghnaim. Tatreez & Tea: Embroidery and Storytelling in the Palestinian Diaspora. Self-Published by Wafa Ghnaim, 2018.

Mohammad, Linah. Children Make up Nearly Half of Gaza’s Population. Here’s What It Means for the War. NPR, 19 Oct. 2023, link

Munayyer, Hanan, and Nathan Sayers. Traditional Palestinian Costume: Origins and Evolution. Olive Branch Press, 2020.

The Revival of Palestinian Traditional Heritage: Documentation of “Inaash” Embroidery over Thirty Years Based on Traditional Old Palestinian Motifs Adapted to Modern Designs. Inʻāš, Beirut, 2001.

Weir, Shelagh, and Sirine Husseini Shahid. Palestinian Embroidery: Cross-Stitch Patterns from the Traditional Costumes of the Village Women of Palestine. The British Museum, 1989.

Weir, Shelagh. Palestinian Costume. British Museum Publications, 1989.

Where We Work: Gaza Strip. United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees in the Near East. Updated August, 2023, link