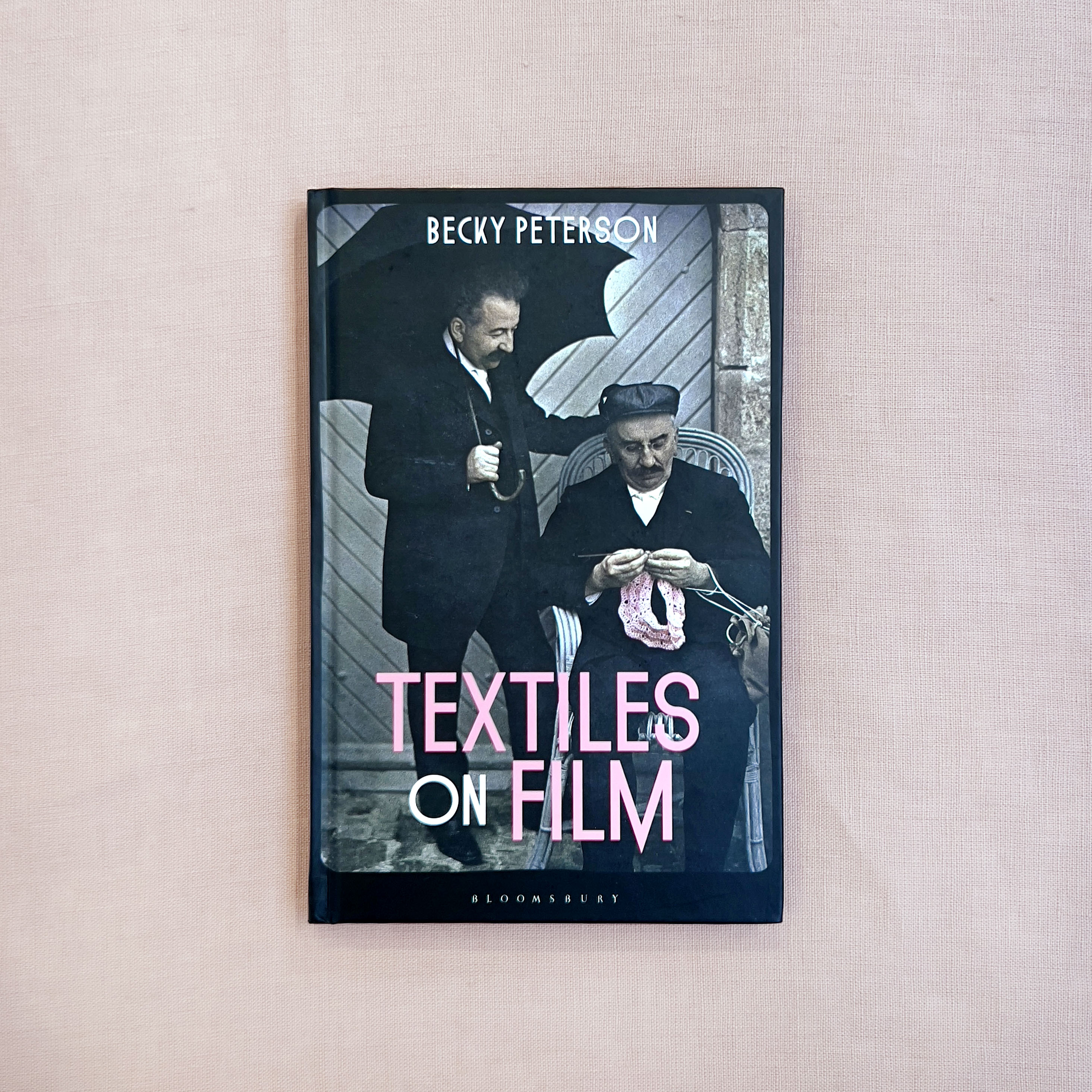

Textiles on Film, by Becky Peterson, is an examination of the cultural and emotional impact of textiles as mediated through cinematic technology. The imagined worlds of the cinematic mise-en-scène are rich with textiles: fabrics drape over sets, serve as props, and develop mood and character through dress and décor. Close readings of on-screen textiles broaden our understanding of the dynamic relationship between fabric and film, redirecting meaning to that which is often overlooked, including depictions of gender expression, behind-the-scenes labor, and architectural and bodily ornamentation.

On Wednesday, September 18th, Tatter will be hosting Becky Peterson’s talk about her research on textiles and film. She will focus on three films, Top Hat (1935), Black Girl (1966), and Blue Velvet (1986), highlighting the ways in which fabric pattern, texture, and construction guide the way we see characters and bodies on film. In advance of her talk, we spoke with Dr. Peterson. You can read our conversation and sign up for the lecture below.

I wanted to start by asking how you came to write about textiles and film.

I started out as a poet, and I was really into the writing of Laura Riding Jackson. In her work, she spent a lot of time talking about dress and bodily ornamentation, like jewelry, which weren’t really things that other poets in her circles were writing about. When I looked into her biography, I found that her family members were garment workers in the New York textile industry. As I talked and thought more about her work, I found other women artists and writers in the mid 20th century US who were doing similar things. These women were in these very theoretical modernist literature circles, and they were paying close attention to the often trivialized details associated with women’s work. At the time I was doing my doctorate in an English department, so I was mainly looking at writing and literature. But I also started reading Anni Albers and I wrote an article about filmmaker Maya Deren’s use of textiles. This led me into thinking more seriously about textiles on film.

One thing I loved about your writing is that you not only look at how a textile functions as an object for viewing or touching, but also how a textile is created and how the construction itself shapes the way that we view it. You talk about satin, which has long wefts floating over the warp, which catches the light and the plushness of velvet, how the pile is punched through to create a lush surface. and how that’s created and how that informs our interpretation of it. Do you have any personal background with making textiles?

I have tried to make textiles, but it hasn’t really caught on with me. I know a lot of people who write about textiles are also makers, but I’m more of an appreciator. Most of my knowledge of the textile industry and manufacturing has come out of the readings that I’ve done, not only by textile and fashion theorists but also labor theorists and labor historians. They were important to include in this study, because in both the film industry and the textile industry there are a lot of people who are never acknowledged for their work.

Along those lines, I wanted to also ask about the craft and industry binary that you mention in the first chapter. You talk about the perception of craft as nostalgic rather than industrious, which can mask the value of the labor and skill that go into both.

People tend to refer to craft and industry as very separate, which contributes to the alienation between textile workers and consumers. In the book, I talk about the 1970s and second wave feminism. You see this interest in textiles as art and in macramé and all those kinds of things and how they were mainly seen as women’s art at the same time as textiles were becoming much more globalized. Because we separate the two, craft is romanticized as being sort of pre-industrial but when you look at the actual construction, it’s a lot of the same technology and techniques and handwork.

In the book you highlight the way textiles communicate on screen in so many films over the last century. Would you tell me briefly why you picked each of the three films that you’re going to focus on for the talk?

I was trying to discuss films where I could find really clear representative clips in which the textiles were prominent and provocative and creating new conversations. I also wanted them to be very different from each other. My discussion of Black Girl is a lot more about patterning and color. When I talk about Blue Velvet, it’s more about texture and tactility, and with Top Hat I focus on light and motion.

Something that was new to me, at least as a concept, was the way that textiles can be presented to us on film to have something called haptic visuality. From what I understand, it’s the way a film can make the viewer feel like they’re touching or being touched by what they see on screen.

Of course, I’m not the first person to talk about that. There are many people working in film studies who are interested in the haptic, but I was interested specifically in how textiles might create that haptic visuality. So for example, in Blue Velvet I discussed how velvet has that quality where if you see it, and you’ve touched velvet before, you can remember the sensation of it. It’s based on memory. And it’s also based on the fact that when we’re watching a film, there isn’t inherent tactility. So how do you create that sensation using only visuals? I’m interested in how filmmakers have tried to get texture specifically from textiles across on the screen.

You write about how, during the Great Depression, audiences would be seeing all these glittering things in the movie Top Hat, while they themselves were so alienated from those luxuries. When it’s not pulling on a sense memory, how does that haptic visuality work?

My answer to that would be that it creates a longing for capitalism and the desire to have something that is not available to you. Top Hat makes it feel somehow in reach and it makes you feel like you know how it feels to touch it.