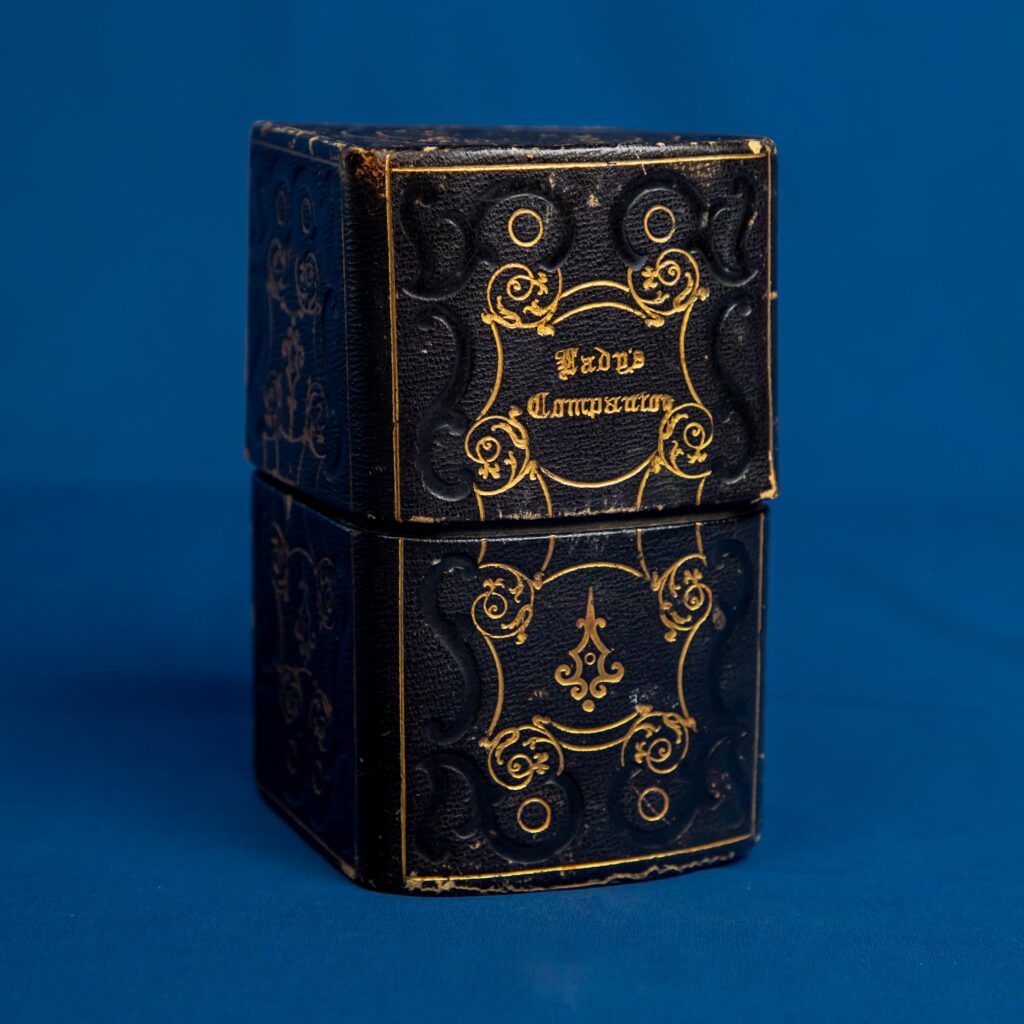

Huddled among the treasures recently donated to TATTER by the Brooklyn Museum lay a group of petite 19th-century sewing boxes, drawing the attention of curious textile lovers like myself and TATTER’s staff. Some are ornately constructed of tortoiseshell and embellished wood, while two more discreet upright boxes stand apart, bearing the inscription “Lady’s Companion.” Despite their decorative differences, all of these boxes fall under the umbrella of what was once a staple of women’s domestic life: the portable sewing set.

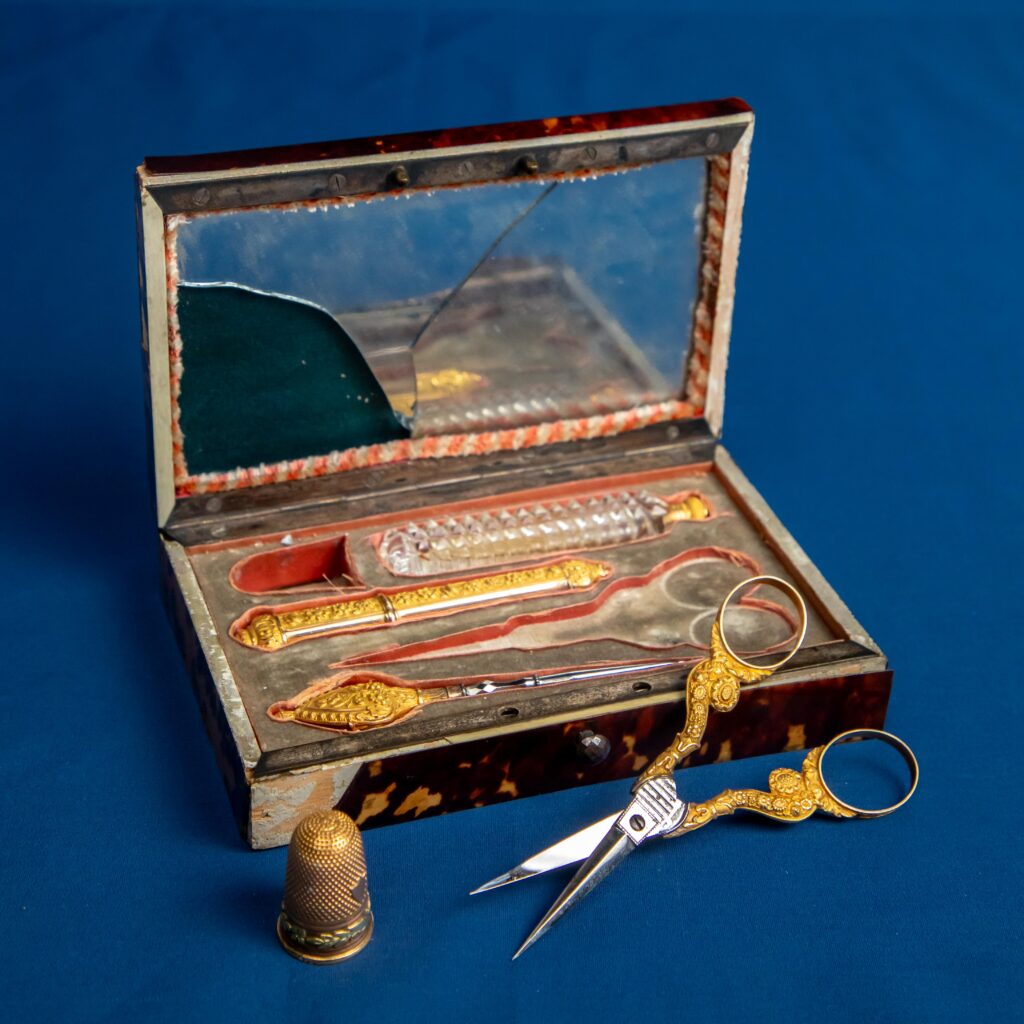

After carefully coaxing these boxes open, owing to the typical puzzling nature of Victorian-era closures, they revealed a miniature world of carefully arranged implements, accessories, and assorted curios. Some items are straightforward, such as mini scissors, needle cases, and thimbles, all expected pieces within a sewing set. Others are more unusual, including glass scent bottles, ear picks, and corkscrews, which nestle closely with sewing tools. Keeping sewing notions on the person, among the most essential of personal items, implies a level of intimacy with stitching that few of us have today.

The history of the sewing set, and more specifically the Lady’s Companion, is closely tied to the quintessential needlework box, which was a commonplace item in a woman’s belongings by the mid-19th century. It would have been typical, if not expected, for a woman of this period to perform all of the sewing duties for her house, leading workboxes to become quite cumbersome. Their stationary nature led to the need for a portable, smaller box containing only the most essential tools. Sewing sets provided the solution to this problem, allowing for emergency repairs and traveling projects.

These sets are generally divided into two categories: the traditional Lady’s Companion typically features an upright standing position, as opposed to the flat alternative. Although the emergence of Lady’s Companions is generally attributed to the mid-1800s, their roots lie in the ornately decorated etuis of earlier decades, dating back to the 18th century. Tracing this lineage further back, these creatively fitted cases speak to a long history of hand-sewing implements and the need to keep them close at hand. Receptacles of a similar shape to these have been discovered in Anglo-Saxon gravesites dating back to the 7th century, which are suggested to have been repurposed reliquaries and used for holding sewing-related items.

Like the larger needlework box, sewing sets and Lady’s Companions were creative in their compartmented constructions, often featuring hidden pockets and fine-tuned recesses for their contained pieces. It took some careful experimentation to uncover the full extent of these boxes and further identify their contents. It is also apparent that they were not designed solely for utilitarian purposes. Some boxes are crafted from luxurious and rare materials, suggesting that these could have functioned as more of a decorative piece than a practical necessity.

All the sets contain the essentials: needlework scissors, a needlecase, a scent bottle, and a bodkin or bodkin container. Yet their materials tell vastly different stories. Some boxes are much more ornate than others, revealing their owners’ likely positions in society. Mother-of-pearl appears to have been particularly coveted, as one wooden set incorporates it across every handle, while another Lady’s Companion takes a more conservative approach with subtle inclusions.

The tortoiseshell box tells the most luxurious story of all. Despite being in poor condition, with a cracked mirror and delicate outer shell, this piece was crafted from rare, genuine tortoiseshell, with inner gilt tools that speak to the considerable expense lavished on even these most private possessions. Here we see clearly that these portable kits served as yet another avenue for displaying wealth and status; their opulence was meant to be enjoyed in intimate moments of daily use, or simply as ornament.

Some of the more curious objects found inside the sewing sets include a miniature tape measure, crafted from bone, mother-of-pearl, and ribbon, nestled in a perfectly fitted pocket in one of the Lady’s Companions. Though smaller than a thimble, the detail paid to even the smallest pieces shows their careful creation. Evidence of their care lies in the absence of rust and debris. The handiness and fine workmanship of these kits demanded attentive maintenance. As most sets were designed and fitted for the exact size and shape of their tools, one lost or damaged piece could never be easily replaced.

The beauty and grooming implements were similarly intriguing, though somewhat cryptic at first glance, and required cross-referencing to identify. One item that initially stumped us was a slim corkscrew tool, topped with a carved mother-of-pearl handle. After some research, I discovered that this was useful for opening scent, ink, and medicine bottles, all of which would have been corked. A creative little piece in the blue velvet-lined wooden sewing set contains a miniature spoon on one end and a pick on the other, used as an ear and nail pick, respectively. Other items found inside include a small crochet hook, an awl, a mini cotton ball, memo pads, a mirror, and a retractable pencil.

The best part of exploring these boxes is the small markers of past owners. Each of these ornate Lady’s Companions tells a story about the woman it belonged to—the wear on a needlecase, or the choice of buttons over bodkin, paint an image of these women’s habits and preferences. A tiny, faded engraving on the thimble within the wooden sewing set reveals a personal dedication. A memo pad in another of the Lady’s Companions reads “O.G. Merle, January 1, 1852,” in delicate script, perhaps suggesting the set was a gift for the New Year. Objects that are missing or unused similarly leave more questions. Entire missing pieces leave their imprint on the velvet cushions, leaving us only to guess what might have filled their place.

After spending a summer working in the depths of TATTER’s archive and collection, I’ve come to understand TATTER as a unique force in seeing and preserving the beauty in everyday objects. Unlike many larger institutions, TATTER’s collecting practices gravitate toward textile-related objects that reveal as much about the people who interacted with them as their aesthetic merits. These sewing companions nestle comfortably into this philosophy, telling a story of quiet work and intimate moments. Although the women who owned and cared for these sets remain unknown to us, the evidence of their lives remains: in the careful maintenance, the personal selections, and the patterns of wear within.

References and Further Reading:

Andere, Mary. Old Needlework Boxes and Tools: Their Story and How To Collect Them. Drake Publishers, 1971.

Rogers, Gay Ann. An Illustrated History of Needlework Tools. Needlework Unlimited, 1983.

Sullivan, Kay. Needlework Tools and Accessories – A Dutch Tradition. Antique Collectors’ Club, 2004.Taunton, Nerylla. Antique Needlework Tools and Embroideries. Antique Collectors’ Club, 1997.

Amelia Ansink joined TATTER this year for a summer internship. Based in Brooklyn, New York, Amelia is a graduate student in the Fashion and Textile Studies: History, Theory, Museum Practice program at the Fashion Institute of Technology. Her work focuses on archiving and collections management, with particular interests in fashion historical research and folk textile traditions.