Dr. Jonathan Michael Square, Assistant Professor of Black Visual Culture at Parsons School of Design and founder of the digital humanities project Fashioning the Self in Slavery and Freedom, is a passionate scholar on the connections and contradictions of fashion history. He combs the archives of historical textile production and reads through interviews of formerly enslaved people to explore the intersection of fashion and slavery as an entry point for exploring larger questions of race, identity, and equity.

“You may not associate fashion with slavery and the transatlantic slave trade,” he said, “fashion – with all its connotations of autonomy and self determination – can actually be the antithesis of slavery. It was the most extreme form of deprivation and selfhood. Enslaved people throughout the Atlantic world leveraged fashion as a tool to exert their freedom and express their diverse identities.”

In a virtual lecture with Tatter on Thursday, May 23rd, Dr. Jonathan Michael Square will present the first chapter from his forthcoming book Negro Cloth: How Slavery Birthed the American Fashion Industry (Duke University Press, 2025). This chapter draws on slave narratives and testimonies collected by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), delving into the intricate web of the fashion supply chain during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It focuses on the connection between Lowell manufacturing and how ‘Lowell cloth’ became synonymous with the clothing of enslaved people.

I sat down to discuss his forthcoming book, Negro Cloth: How Slavery Birthed the American Fashion Industry, and lecture at Tatter, You can read our interview and sign up for his talk below.

How did you find the connection between Lowell Massacheussets and clothing for enslaved people?

It started as an outgrowth of the scholarship that I was doing on the testimonies by enslaved people. The testimonies were interviews done in the 1930s, so they were older people who had been enslaved as children in the late 19th century. Most of the descriptions of clothing for enslaved people in catalogs or escaped slave advertisements or in enslaver expense records used terms like ‘negro cloth’ or ‘homespun.’ But formerly enslaved people from across the south used the term ‘Lowells’ or ‘Lowell cloth’ to refer to clothing worn by enslaved laborers on plantations. It’s interesting because even clothing that was made somewhere else or even clothing and textiles made on the plantation where the enslaved people lived were called Lowells. Because Lowell textile factories were producing this cloth on such a large scale, they became synonymous with negro cloth or the clothing of enslaved people.

Would you speak a little to some of the typical characteristics of clothing for enslaved people?

In the interviews, they often described the clothing being durable but also uncomfortable. They were also meant to identify people as enslaved, and make it harder for people to escape or pass in society. Particularly in the American South and in the Caribbean, enslaved people weren’t given shoes and their clothing didn’t have pockets. Clothing for children was totally ungendered, basically smocks, and then different fabrics and styles were available for men and women. Men tended to have very plain clothing, like a loose shirt or tunic and large pants with a drawstring that weren’t really sized. Calico cloth was more associated with women, who would have worn largely shapeless dresses with aprons.

Of course, clothing also depended on the type of labor the person was doing and how wealthy their enslaver was. People who worked outside typically wore Lowell cloth or negro cloth, whereas people who worked inside more typically wore second hand clothing from the household or livery. I actually have another chapter where I write about Brooks Brothers and the manufacture of livery. But yeah, those simple garments were just the basics. Usually there would be some kind of coat for winter, and enslaved people were also often given an allotment where they could grow food to supplement their diet or sell to earn a little income. Often they would buy ribbons or cloth or second hand clothing to wear on special occasions. The Lowell cloth garments were sort of the cheapest and most basic items.

Is Lowell still producing textiles?

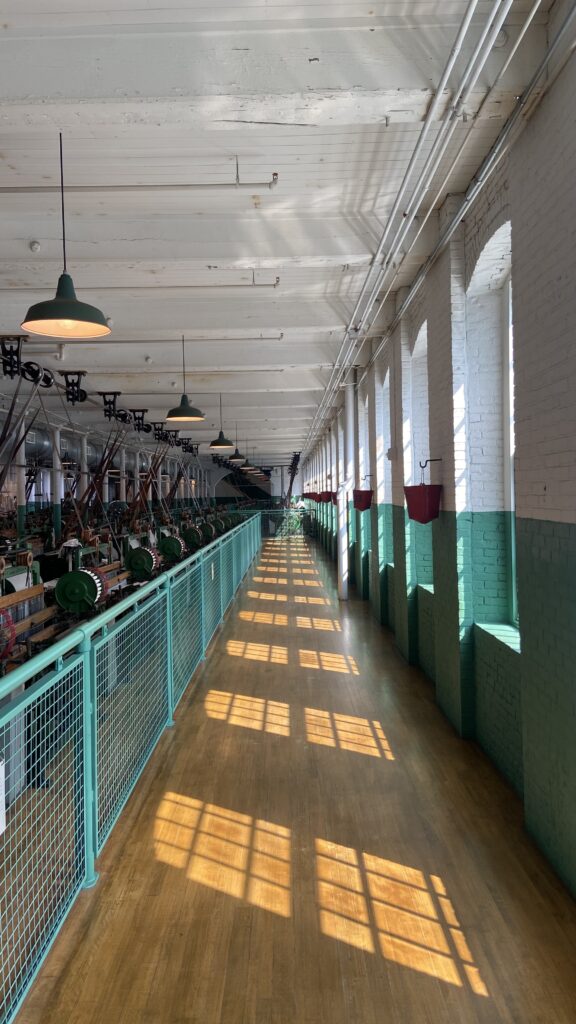

Yes, it’s actually a really interesting story. I’ve been to Lowell and they have turned a lot of the factories into museums where they talk about the history. I actually have a textile from Lowell, I’ll show it during the talk. At the museums they do touch on Lowell’s creation of clothing for enslavers but it’s not at the forefront. What they focus more so on are the people who worked in the factories, the unmarried white poor women from New England called Lowell girls and politically active immigrants, often communists and socialists. There’s a whole body of scholarship on them, because they lived in factory housing and they were often literate and had their own newspaper. Many of them were suffragists and abolitionists, though they don’t seem to have connected much of their political activism to the material fact that they were making clothing for enslaved people.

Were you able to see any examples of Lowell cloth clothing?

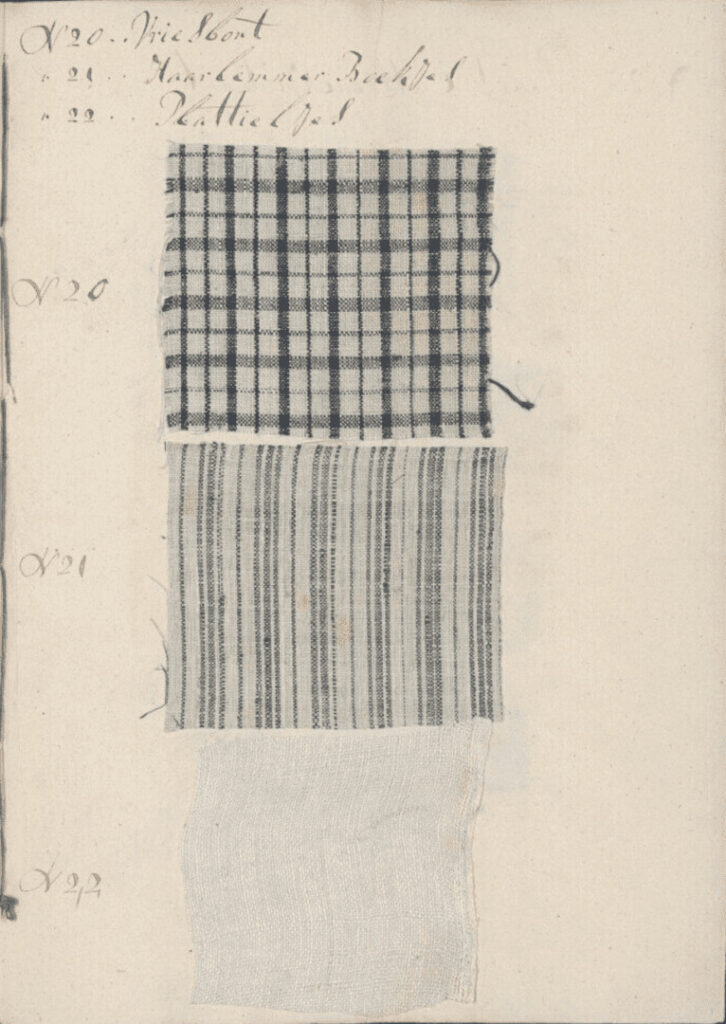

Not of the clothing, no. This stuff was made to be used, like it was worn until it fell apart and unusable clothing was turned into rags or used to patch other garments. It also didn’t have the sacredness of a silk ballgown, so nobody wanted to preserve it. I have been able to see some samples of the cloth from Lowell manufacturing books in the Harvard Business Library. It’s basically roughly woven unbleached cloth. The main thing mentioned consistently in interviews is that it was uncomfortable. There was no attempt by enslavers or manufacturers to make it something anyone would choose to wear.

LEARN WITH DR. JONATHAN MICHAEL SQUARE

OUR LECTURER

Dr. Jonathan Michael Square is the Assistant Professor of Black Visual Culture at Parsons School of Design. He earned a PhD from New York University, an M.A. from the University of Texas at Austin, and a B.A. from Cornell University. Previously, he taught in the Committee on Degree in History and Literature at Harvard University and was a fellow in the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He curated the exhibition Past Is Present: Black Artists Respond to the Complicated Histories of Slavery at the Herron School of Art and Design, which closed in January 2023. He is currently preparing for his upcoming show titled Afric-American Picture Gallery at the Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library. Dr. Square also leads the digital humanities project Fashioning the Self in Slavery and Freedom.