For International Women’s Day, our content coordinator, researcher, and designer of the Poetry Mittens Project Elliot Rockart has written a piece reflecting on the book which shaped their practice: ‘Women’s Work: The First 20,000 Years.’’ Below, they describe their own entry into textile art and recreation of historical textiles.

For most of my childhood, I spent my summers at my grandparents’ house in the tiny town of Averill, Vermont. Rainy days were common and interminable, sometimes stretching for days on end. With an almost forty minute drive to the nearest library, there were few indoor activities available outside the house, and I would often make the soggy but short trek to the Lake View Store which my cousins and I knew only by the name of its owner, Priscilla Roy.

Priscilla’s was a magical place. Penny candy winked from behind the counter and various treasures of sweets, stationary, knitting supplies, local crafts, and stacks of worn, paperback books occupied every inch of space. Priscilla lived in the back of the store with her mother Jeanette. Both of them skilled craftswomen, they knit, crocheted, quilted, sewed, and even spun yarn on a beautiful, old spindle in the corner of their living room. It was there that I first learned to crochet, in the rainy summer of my eighth birthday. Priscilla’s patient hands guided mine as we listened to Car Talk Radio on a couch piled with handmade quilts and afghans.

The next year, another of my grandmother’s friends taught me to knit. I sat with her, alongside her own granddaughters on the couch, watching movies on a VCR. The other girls would only knit a few rows before, blessedly, sun would break and they would run back outside. There was something different about it for me. Something more sacred about the puzzle of turning fuzzy balls of yarn into the crooked cloth of a short, uneven scarf. I loved presenting what I made to Priscilla, that generally brusque and skilled needlewoman, who always had something kind to say about my latest project.

Some rainy days I would go to Priscilla and offer my services organizing her stacks of second hand books alphabetically by author. In return, she would knock the price down from 50 cents per paper back to twenty-five. The summer I turned twelve, I picked up an unassuming yellow paperback with an ambitious title: Women’s Work, the First 20,000 Years, written by Elizabeth Wayland Barber. It started me on a journey that has shaped the past decade of my life and taken me to Brooklyn and to Tatter: studying the mysteries of cloth and making it myself.

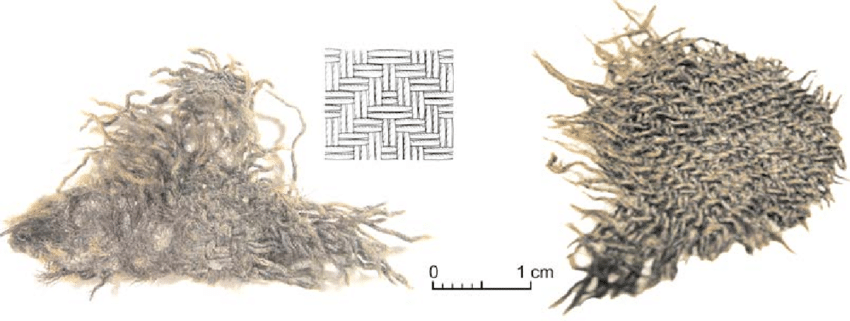

Iron Age woven cloth from the Hallstatt salt mines. Courtesy of Natural History Museum, Vienna.

Barber opens Women’s Work with a story that could have taken place in just about any century, and just about anywhere in the world: warping a loom with her sister. The two are carefully measuring out the yarns, passing the skeins back and forth, a little exasperated with their task after hours upon hours of careful work. As they transferred the warp to the loom, Barber checked and rechecked their work against the carefully drawn heddle chart, making sure she had gotten the colors in the right place.

The yarn had taken some effort to source. Unlike most yarn today (carded and fluffy), this yarn was combed for a stronger, firmer fabric. After all, yarn has only been carded (pulled apart on metal toothed brushes so that it lays together in all directions rather than being combed into firm lines) since the Middle Ages. The scarf Barber was attempting to make was a recreation of one that had been woven several centuries before the technique was made popular. Barber had seen the scarf fragment, only the size of an open hand, in the National History Museum of Vienna two months previously. She had been drawn in by the green and brown colors of the wool, preserved for three thousand years in the Hallstatt Salt Mine in the Austrian Alps as well as the distinctive pattern of the weave now known as ‘Hallstatt Twill.’ The fragment, torn from the scarf of a miner and lost for millenia, had no edges with which to orient the textile. By attempting to recreate it, Barber made an important discovery: that her struggle warping the loom had come from a mistake in how she had read the cloth. The warp should have been the weft! She could learn how the weavers worked– how they made exacting patterns quick and intuitive, how they shared the labor– by putting her own hands to the task. As a twelve year old, I was totally awed by the story. I wanted, immediately, to put my own hands to the task of learning to read history from the shape of a textile.

Wool twill textiles from Hallstatt, Austria, 1500-1200 BC (HallTex 211 and 275) (© NHM, photo: A.rauSch).

Textile history is largely regarded as women’s history, and thus it remains largely ignored, underfunded, and underappreciated. Garments, bedding, decoration, furnishing, the literal fabric of our lives are so integral to our day to day lives that they are generally regarded as commonplace, uninteresting. They are material culture, crafts, often treated today as highly disposable. Yet every stitch of clothing we wear, every carpet we walk upon, every pillow upon which we lay our heads at night, is the result of nearly 20,000 years of innovation and the work of millions of hands. According to the International Labour Organization, today nearly 60% of garment workers globally are women, reaching nearly 80% in some regions. The numbers are skewed by the fact that most of the lowest paid garment jobs– the ones that can be done from home, the ones that aren’t officially recorded, the ones with the highest levels of exploitation– are done by women. Their labor is rarely included in these numbers.

Women’s Work, that unassuming 300 page paperback book I found in the same little building where I learned to crochet, contains a staggeringly comprehensive, thoughtful, and fascinating overview of global textile history. I recommend it to everyone, and I reread it frequently.

It contains an analysis of the musculature of the Venus de Milo’s upper arms which suggests that her missing limbs would have been engaged in the act of spinning, tracks the movement of the Hebrew slaves from Egypt as Egyptian linen weaving techniques traveled to Palestine during the time period believed to match with the Biblical Exodus, and follows the cuneiform tablet complaints of a professional weaver sending her textiles to her husband across East Asian trade routes. It suggests explanations for why textile work is so often the work of women, and how women’s material contributions have shaped and recorded history.

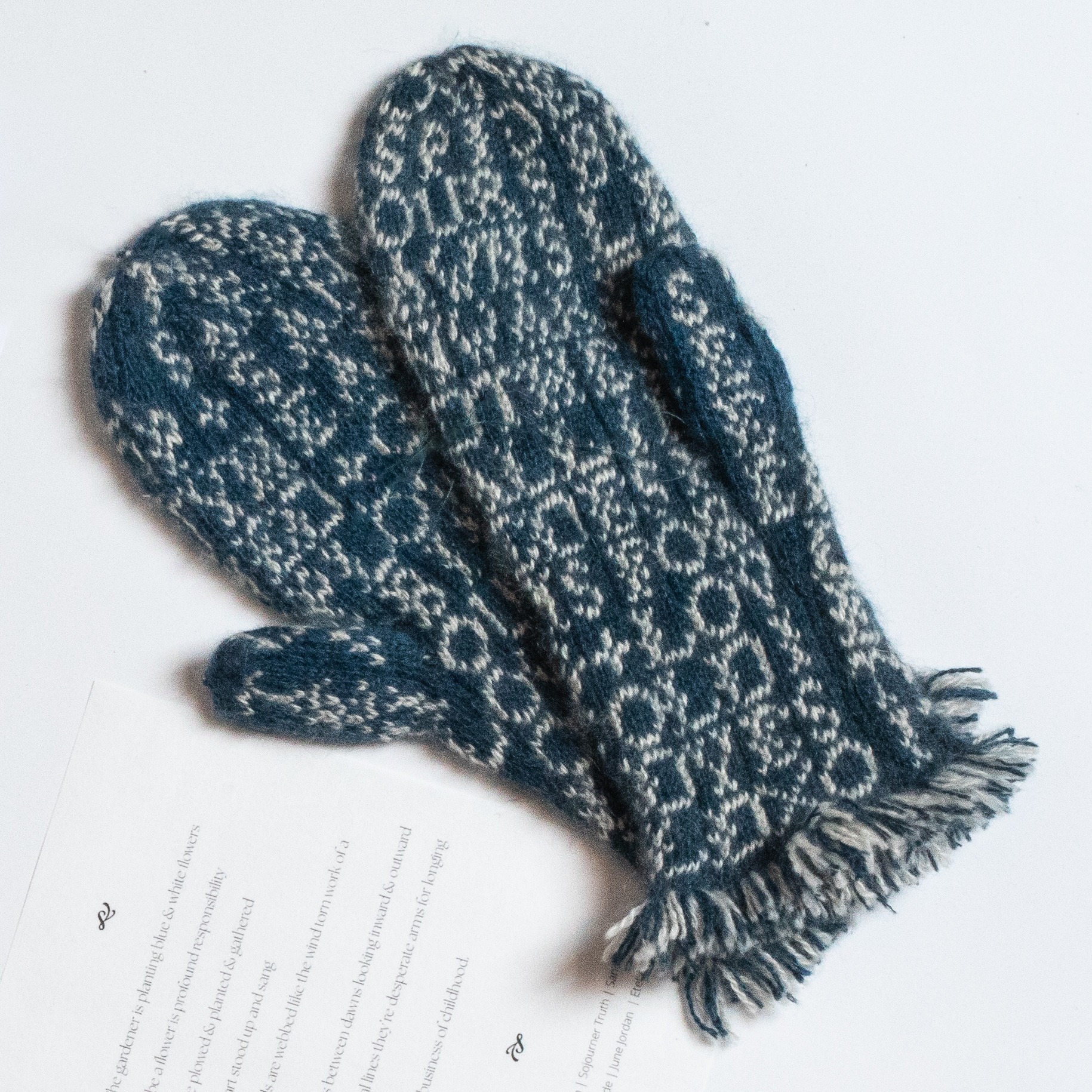

Today, on International Women’s Day, I am thinking about all the women whose work has shaped my own practice as a textile artist and historian. Scholars like Elizabeth Wayland Barber, artists like the unnamed woman who knit the poetry mittens I had the opportunity to recreate for Tatter, and of course my own crochet teacher, Priscilla Roy, who passed away in 2017. Every person I have taught in the decade since crochets with her hands as a guide, hands guided by her own mother and on and on back through the centuries. To unravel that past, that lineage, is to put our hands to the never-ending work of preserving, reworking, and recording women’s history. It is a task that I am honored to be a part of at Tatter, and one which we invite you all to join us through classes, lectures, essays, journals, artifacts, and of course, all the books in our library. If you’re looking for a place to start, I recommend you come and visit us. On the top shelf of the library stacks immediately to the right of the door, you will find ‘Women’s Work, The First 20,000 Years: Women, Cloth, and Society In Early Times.’

Elliot Rockart is a textile artist, crafter, and researcher based in Brooklyn. They are a content creator and product designer at Tatter where they are able to combine their love of history and textiles to create knitted, crocheted, embroidered, woven, hooked, and appliquéd art.

You can read more about their work at ecrockart.com or follow them on Instagram and Tiktok at @myweeklyarn