The story of how I met the blue mushroom starts with growing up in Latvia, a country where the national sport is not football, but rather mushroom picking. As soon as the first photos of chanterelles appear on Facebook feed, almost every casual conversation involves questions like: did you go mushroom picking this weekend? Are you freezing or drying the mushrooms this year? Which forest did you forage in?

The location of the best mushroom spots is a flirtatious secret shared only with closest friends and family members. Sometimes not even. My grandma still ventures off to her Penny Bun spot, whose whereabouts none of us know, to collect the edible boletes. Playful bragging is part of the tradition. When crossing paths with another mushroomer, there is a saying: “each mushroomer has their own mushroom to find,” meaning that one can find only those mushrooms that are calling to you, the forager. It is surprisingly true. The knowledge of edible mushrooms is passed from generation to generation by weekend walks in the forest. Usually, however, it is limited to a dozen or so edible species. The rest are simply called “dog mushrooms.”

This year foraging changed. A book written by two Latvian mycologists compiled all mushrooms that can be found in Latvian forests in one Big Latvian Mushroom Book. The fungi encyclopedia has not only a five star rating system for tastiness but also includes all inedible mushrooms, and very detailed instructions on how to recognize species by look, location, smell, and sometimes even taste when lightly touched to the tongue. The book seems to rekindle traditions, inviting mushroom hunters to look beyond a few edible species – to become observers in a curiosity game, where the ability to identify is just as exciting as eating. It is worth noting that the mushrooms that are picked are only the fruiting bodies of the organism’s vast mycelium found underground – which is why they keep appearing in the same spot year after year. Mushroom picking is not harmful for the reproduction of fungi. Arguably, the forager helps the organism by spreading its spores.

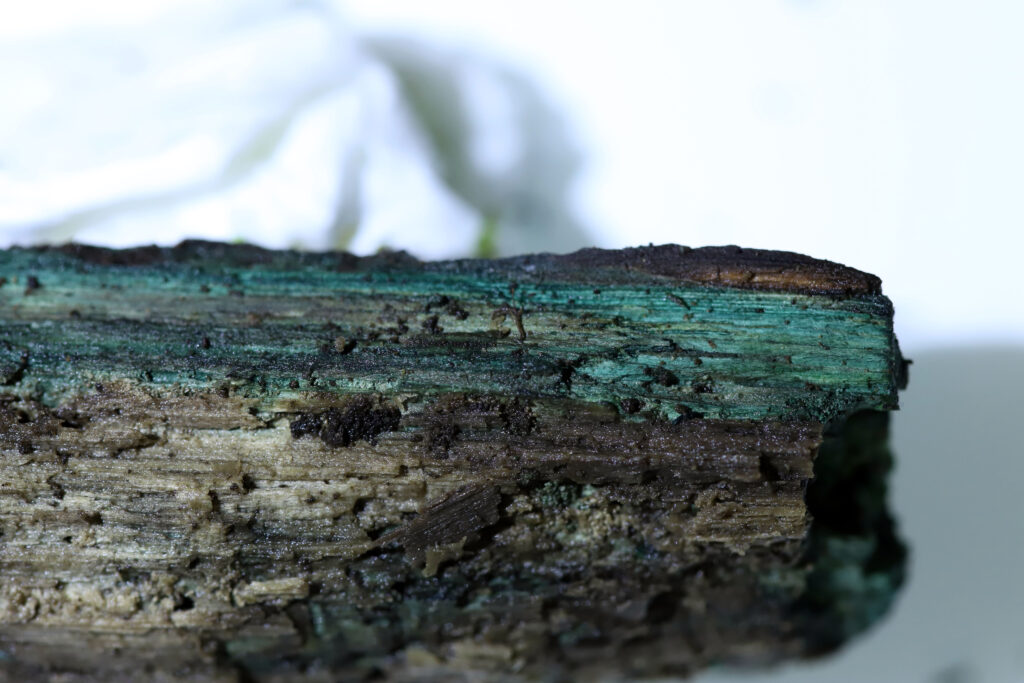

So there I was, escaping lockdown through the pages of a printed Latvian forest. Flickering through this new book, I noticed a mushroom that looked like nothing I had seen before. It was a photo of bright, blue coloured wood and small cup-shaped turquoise mushrooms. “Wow,” I thought, “that must be a bit of Photoshop and loads of luck to find one.” To my surprise, underneath the stunning photo was written: “commonly found.” From that moment, my forest walks were dedicated to finding Chlorociboria aeruginascens, the Blue-Green Elf Cup. Finally, on one fall day, I found a piece of wood stained blue. I knew immediately what that blue stain would lead to. Stunningly bright turquoise, with a few tiny cups emerging, was Chlorociboria – the extraordinary blue mushroom.

The location of the best mushroom spots is a flirtatious secret shared only with closest friends and family members. Sometimes not even.

Photo by Marine Renaudineau

Photo by Maël Hénaff

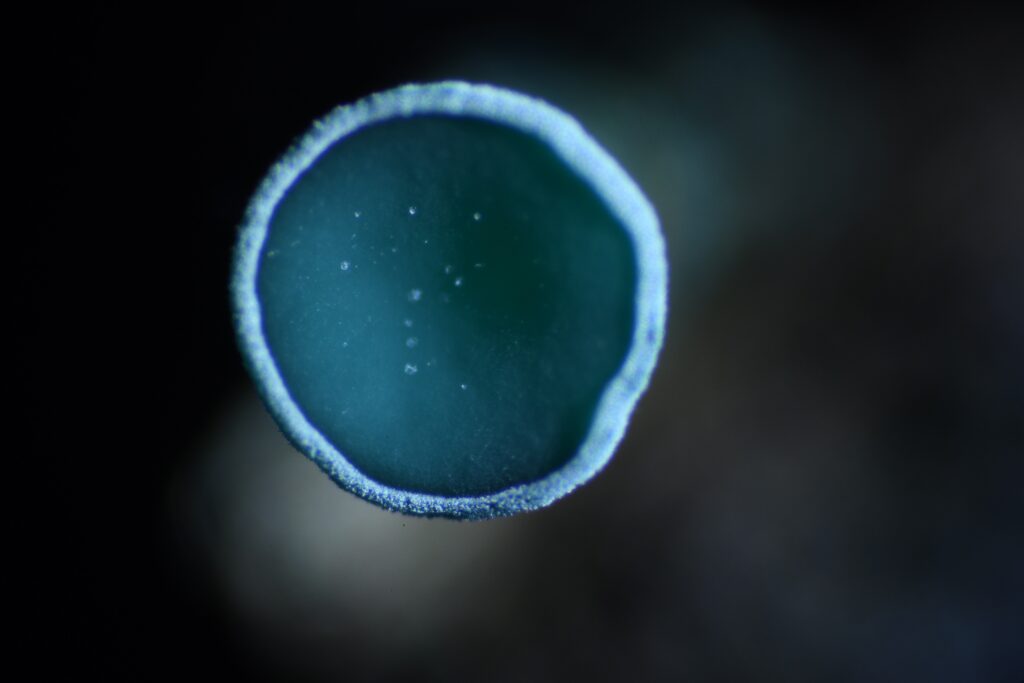

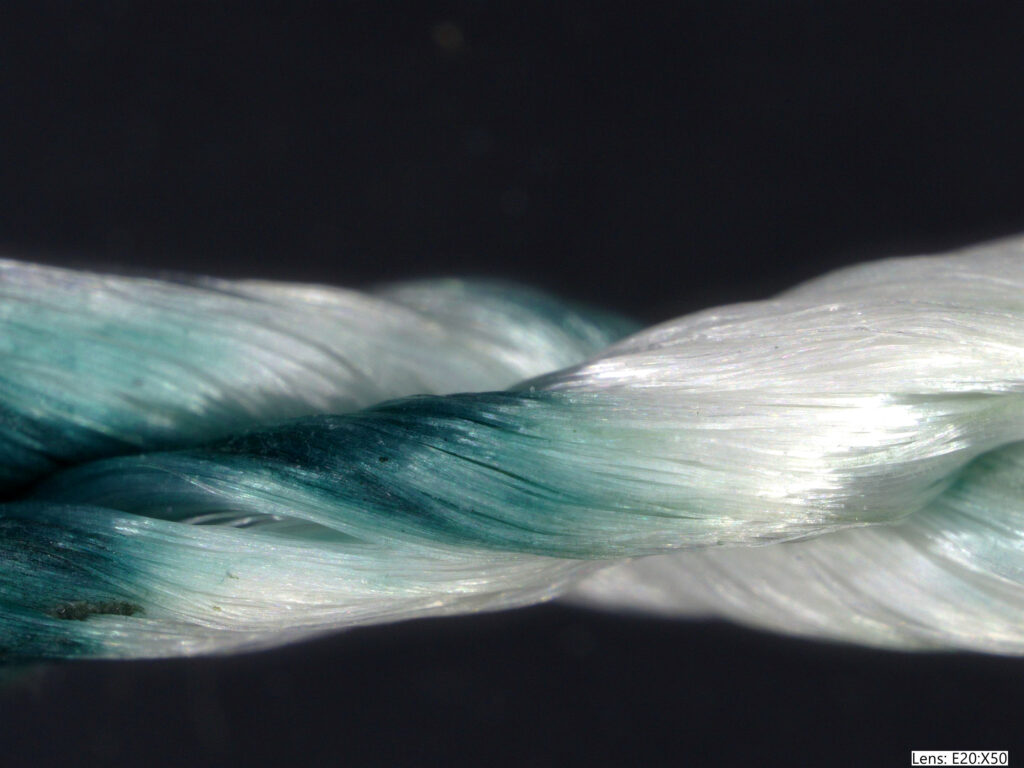

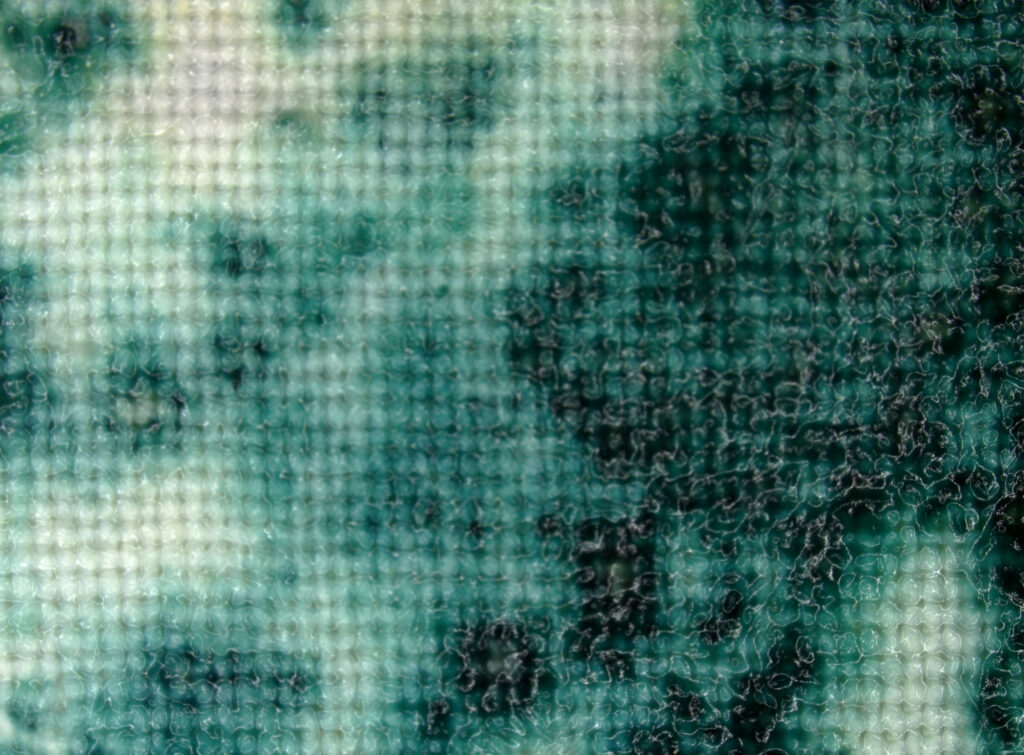

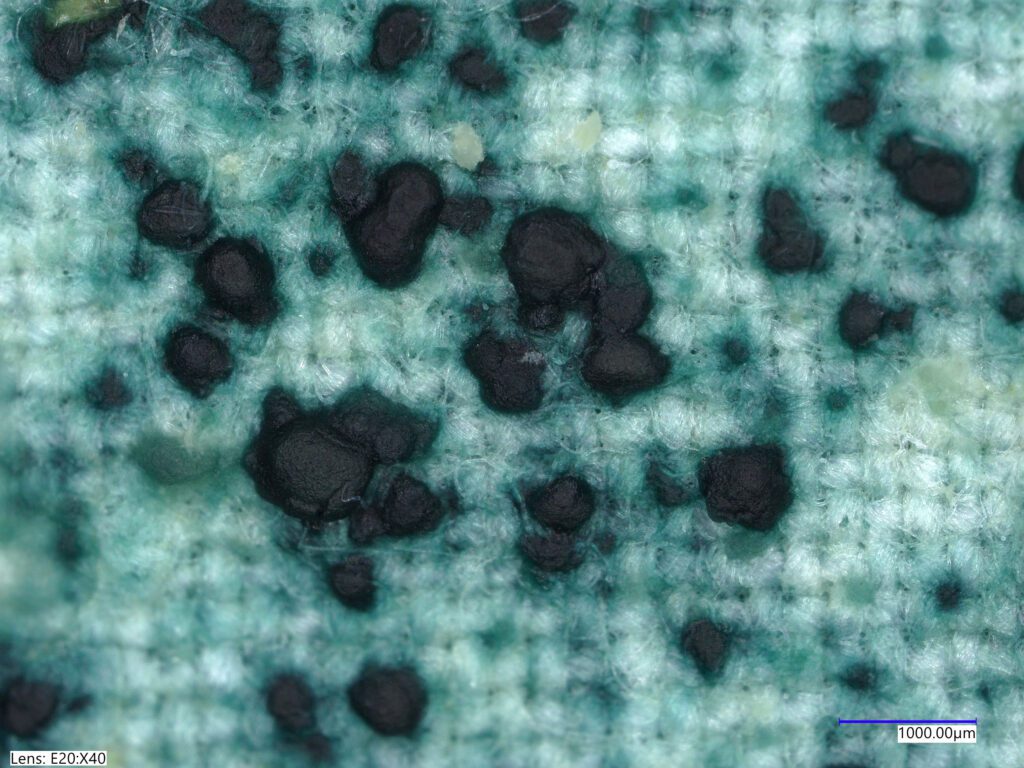

Under the microscope, the mushroom’s intricate mycelium net had crawled throughout the fiber and carried pigment with it. It was like my friend was finally beginning to respond to my questions.

My interest in the blue mushroom was more than a curiosity. I’m a textile designer and I have seen the complex journey raw materials go through to become colourful fabric. It is jumbled and – even with the best of efforts – it is a system that is untraceable and inherently unsustainable. In my practice, I look to nature’s processes to create materials, cloth, and colour. Colour, in particular, is a painful topic for those who are working towards sustainability, as the environmental cost of synthetic dyes is very high. It is estimated that one-fifth of global water pollution comes solely from textile finishing. Yet there are not many alternatives to synthetic dyes that demonstrate equal vibrance and the ability to retain the shade after the endless washes we have grown used to. For that reason, the textile sustainability crisis itself has sometimes been called “a crisis of color”.

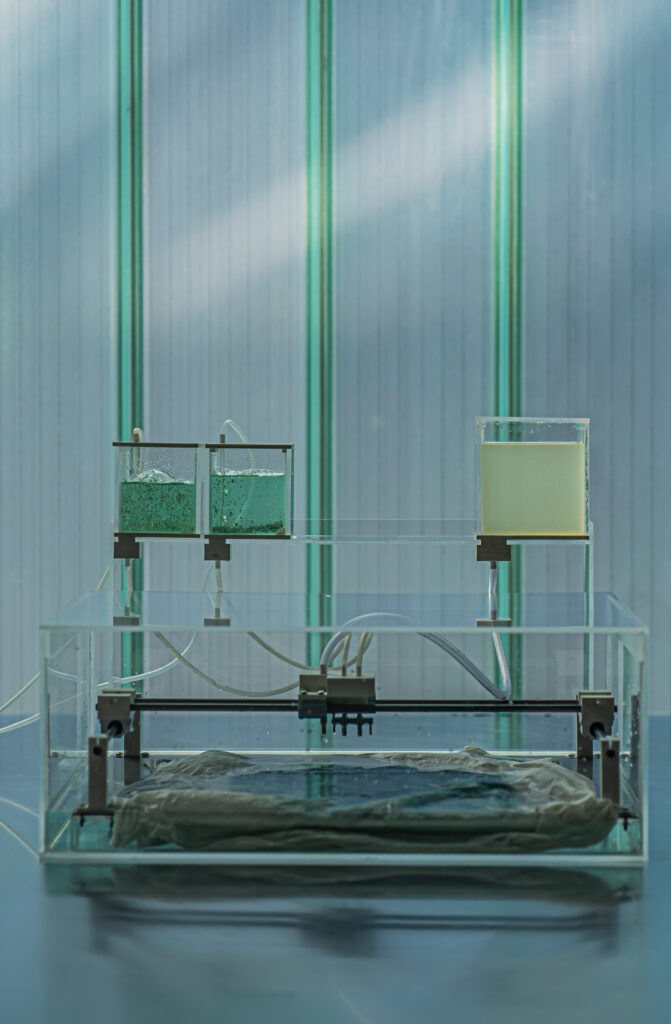

When I observed that this extraordinary mushroom colours wood in vibrant, colourfast turquoise, I first needed to start a conversation with it. When found in nature, most microorganisms cohabit the smallest spaces; separating them is a challenge. Eventually, after a few unsuccessful isolation attempts, I asked a mushroom library to send me a sample from their collection.

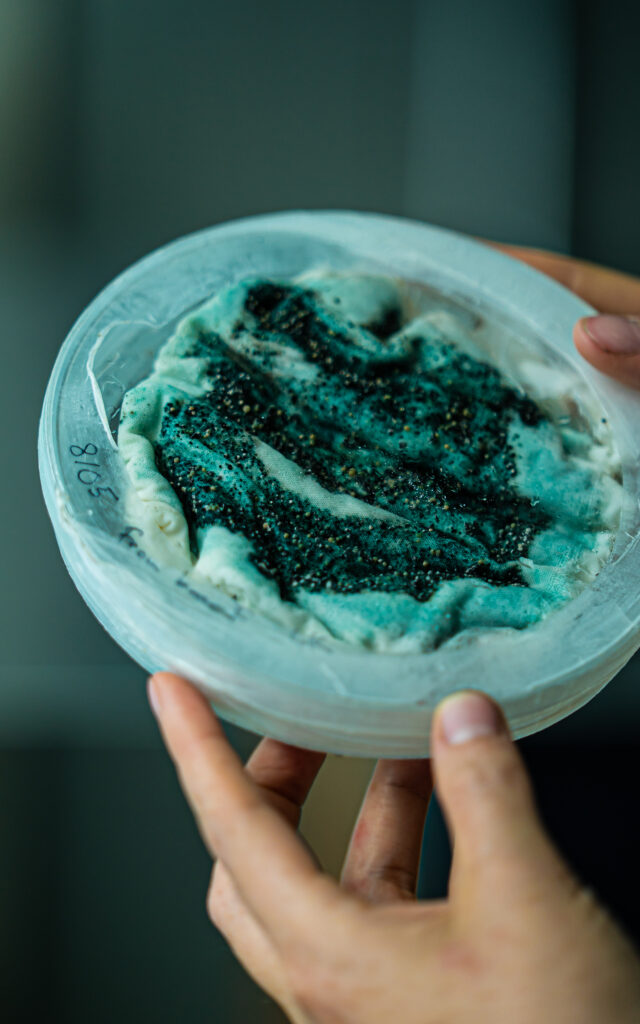

When I received my new-to-be best friend in a glass vial, I did not recognize it. The turquoise blue was absent. Instead, there was a small dot of contented white fluff. I soon learned that the pigment produced by an Elf Cup is a response to stress; so when the mushroom is happy and healthy, it looks white and fluffy. It is theorized that the production of pigment could be a way to protect its food source from other organisms. The human eye perceives this most obviously as a stained wood inhabited by the Elf Cup – usually a mushroomer’s first clue that Chlorociboria is growing there.

For the next few months, I became friends with the mushroom – finding out what food it eats, which temperature it’s comfortable in, and the vessel it prefers to live in. Then, slowly, I changed the environment, and introduced textiles, yarns, and other fibers as its new home. It was especially important to develop a feel for when my new friend was happy, slightly stressed, or unwell, because the colouring only occurs in particular stages of the spectrum. The mushroom grows serenely at its own – imperceptibly slow – speed. Often I was left dreaming of a time machine that could speed up the blue growth according to my wishes. But warping time was not possible. So instead, my research was planned, and deadlines were moved to suit the pace of the blue mushroom.

Only after half a year of friendship did I see the first blue spot on a piece of yarn – the miracle that I had been waiting for. Under the microscope, the mushroom’s intricate mycelium net had crawled throughout the fiber and carried pigment with it. It was like my friend was finally beginning to respond to my questions.

Photo by Maël Hénaff

Photo by Maël Hénaff

Photo by Liene Kazaka

The location of the best mushroom spots is a flirtatious secret shared only with closest friends and family members. Sometimes not even.

Perhaps, in the end, what matters most is our relationships with the environment and the source of our color.

Since this initial appearance of blue, I have worked to explore further the release of a turquoise pigment into the objects the Elf Cup grows on, observing the patterns created by its spread across the fabric. The blue-green pigment produced by the mushroom has shown equal colour fastness measurements to commercial dyes, allowing me to imagine a future where fabric is coloured solely by living organisms that need only a small amount of water and nutrients.

It’s important to mention that I am not the only one to fall in love with this particular fungi. Found on a forest floor, blue wood stained by the elf cup has long been used in woodwork design and mosaics. In the Renaissance, the blue stained wood was seen as a mysterious phenomenon of nature. But, like many natural colourants, it was forgotten when synthetic dyes became available. While it was known that fungi are responsible for the coloured wood, the colouring process was not entirely understood or explored. Today, scientists and innovators are looking into the world of fungi, seeking understanding, and perhaps discovering useful knowledge that can be used for a better future.

The bond I developed with my mushroom was much like a gardener has with their plants. The feeling of nurturing followed every step of the way, from selecting what to grow, to learning cultivation, and finally to harvesting. How would the world change if all manufacturing and design were undertaken with the feeling of nurturing? What if we saw the living things as our kin and the planet as our garden? Perhaps, in the end, what matters most is our relationships with the environment and the source of our colour.

The possibility of looking at my turquoise clothing and understanding blue’s origin as a playful collaboration with the blue mushroom excites me. The re-discovery of an intimacy with colours offers me hope for preserving colour in textiles. Well – blue at least.

Liene Kazaka is a designer and researcher who works on projects exploring material-based storytelling through investigative topics around sustainability across multiple disciplines. She is particularly interested in working with living systems in search of better fabrication methods that carry a story of human-nature relationships.

After graduating BA Textile design (First Class Honours) in Heriot Watt University, Scottish Borders she has worked as a woven textile designer for a luxury market where she gained experience in the traditional and current textile manufacturing methods. To satisfy the curiosity of alternative design approaches, she continued her education in MA Material Futures at Central St Martins. While studies, Kazaka’s practice turned towards an interdisciplinary approach and experimental material research. Her latest project Myco Colour explores living fungi to colour materials – a new and sustainable dyeing method.

To learn more about the work of Liene Kazaka visit lienekazaka.com / @liene_kazaka

Top left photo by Liene Kazaka.

Bottom left photo by Maël Hénaff.

Right photo by Maël Hénaff.