THAT SUMMER CHANGED THE WAY I THOUGHT ABOUT THE OCEAN.

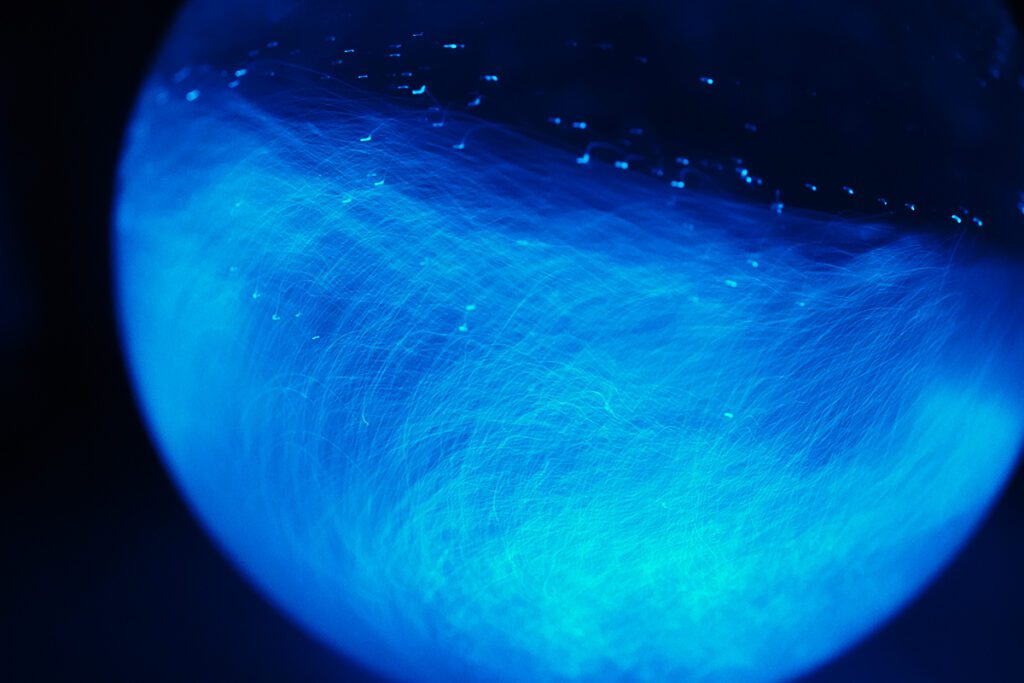

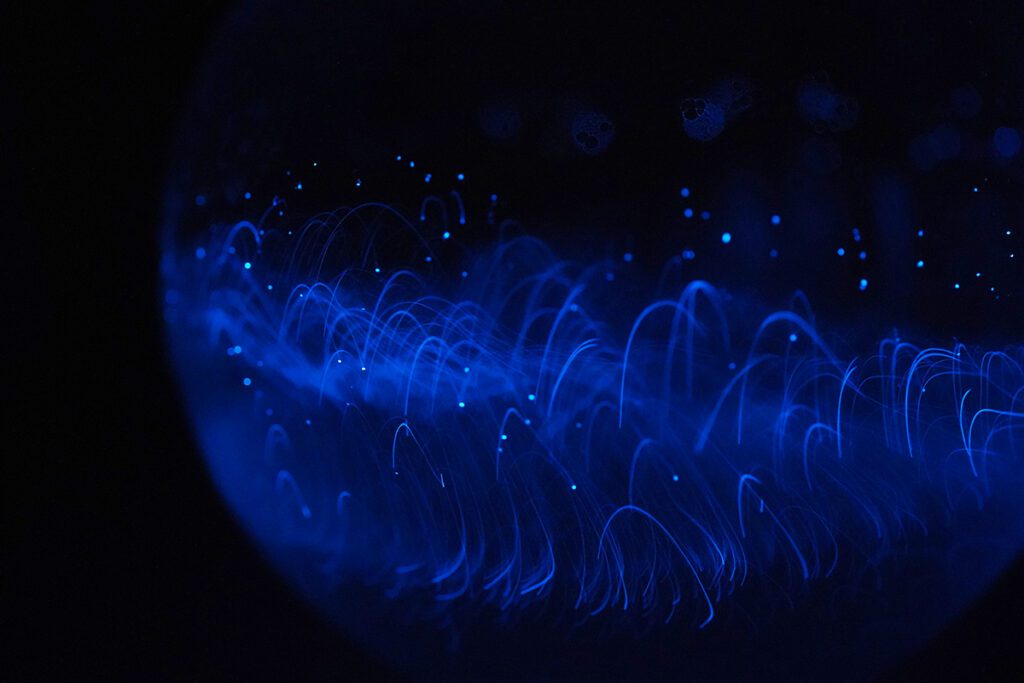

Under a waxing moon, my partner and I sailed our 37-foot sailboat, Bear, down the Chesapeake from Annapolis to Solomons Island. The sky was inky and the water flat calm for the last few hours. As per tradition, we set the anchor and hopped in our dinghy to go to shore for a celebratory cocktail. As we pulled away from Bear, the waters around the dinghy began to light up like fireworks reflecting in a pool. Brilliant blue light danced on the surface. This was my first experience up close and personal with bioluminescent dinoflagellates, and it spurred my cross-species creative research with this incredible light source.

That summer changed the way I thought about the ocean. It was the first season that we lived aboard our boat, traveling, working, entertaining, and recreating by the weather and tides. The rhythm of the sea became the rhythm of our lives, dictating our movements and moods. The bioluminescent sighting set off a flurry of synapses and a flood of curiosity that fueled my desire to better understand marine ecology and the interconnections of life.

The following year we added Solomons Island to our sailing itinerary again, so that I could spend more time with the sparkling seas. I returned to the same anchorage at the same time of year, excited to see the bioluminescence. I was met with disappointment. The blue was absent.

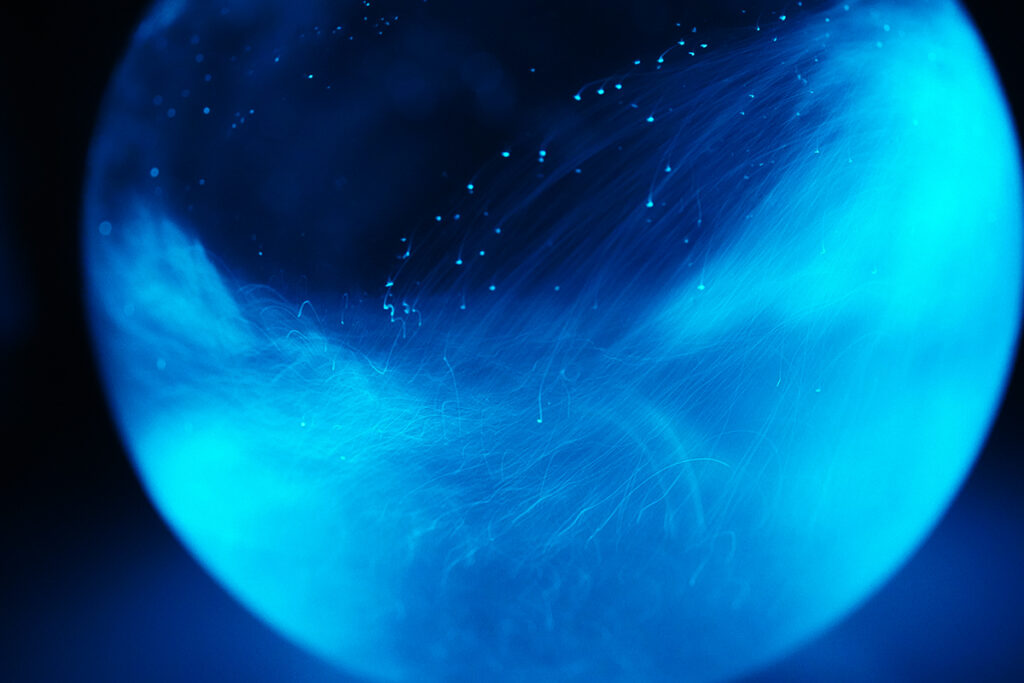

The following fall, I returned back to my academic position at Bradley University in Peoria, IL, with a need to understand why the blue light had been snuffed from the sea. I received a grant from the university to start a new research project investigating the power of bioluminescent organisms in the field of photography. I titled the project Growing Light; and I began by culturing the dinoflagellate Pyrocystis fusiformis, which are similar to the organisms I saw in the Chesapeake Bay. These single-cell marine plankton can generate a bright blue flash of light using a luciferin-luciferase chemical reaction. This biological capacity appears to be useful for startling potential predators, and it is commonly seen in the wave action at popular tourist sites, including Mosquito Bay in Vieques, Puerto Rico and Sam Mun Tsai Beach in Hong Kong.

The rhythm of the sea became the rhythm of our lives, dictating our movements and moods. The bioluminescent sighting set off a flurry of synapses and a flood of curiosity that fueled my desire to better understand marine ecology and the interconnections of life.

I made many mistakes in the beginning as I struggled to learn the proper handling techniques and environmental conditions that the organisms needed to survive. My studio made a slow but steady transition to lab space as I came to understand the circadian rhythm of the dinoflagellates, a life cycle that requires nurturing with the proper light, chemical, and temperature conditions.

With a longing to learn more about these organisms and the hopes of finding kindred spirits, I reached out to two bioluminescent specialists, Dr. Edith Widder of the Ocean Research and Conservation Association, and Dr. Jim Sullivan of Florida Atlantic University’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute. Both researchers were incredibly generous with their time and even shared “recipes” with me for the best way to chemically create sea water in which to culture dinoflagellates.

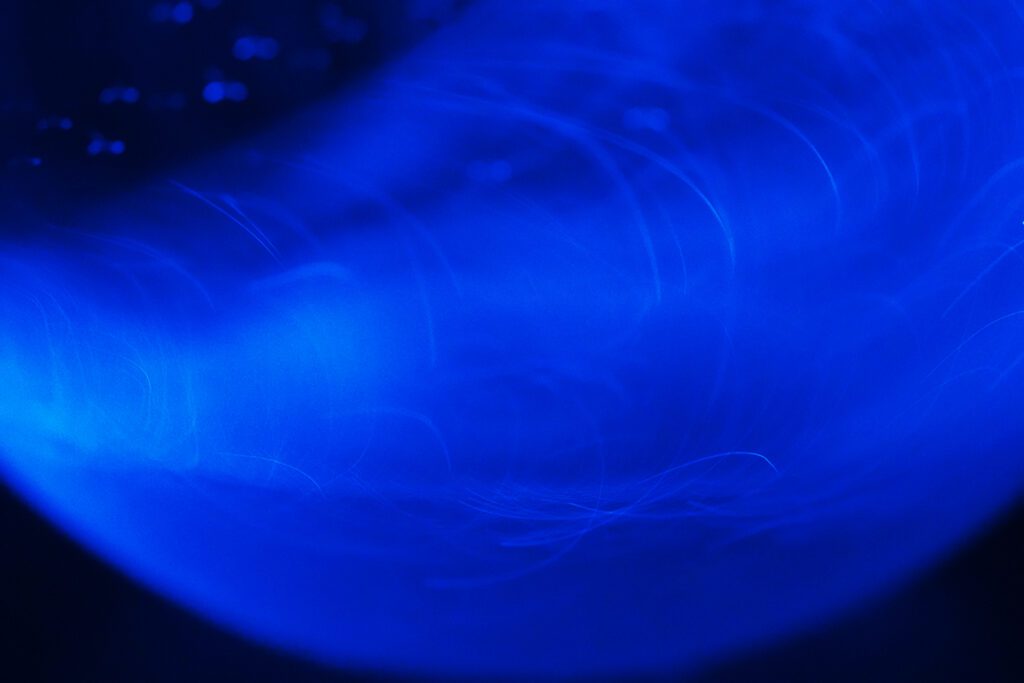

With the help of these scientists, and additional colleagues in the biology department at my home institution, I was able to successfully “grow” these organisms. I began to feel a kinship with the tiny glowing beings and found great joy in collaborating with them in the darkroom to create images. I shifted my working hours to be present during their more potent light-emitting hours, and developed a delicate system of movements to encourage light emission. The process was never a project of one – it was, and continues to be, a partnership that is cross-species and cross-discipline.

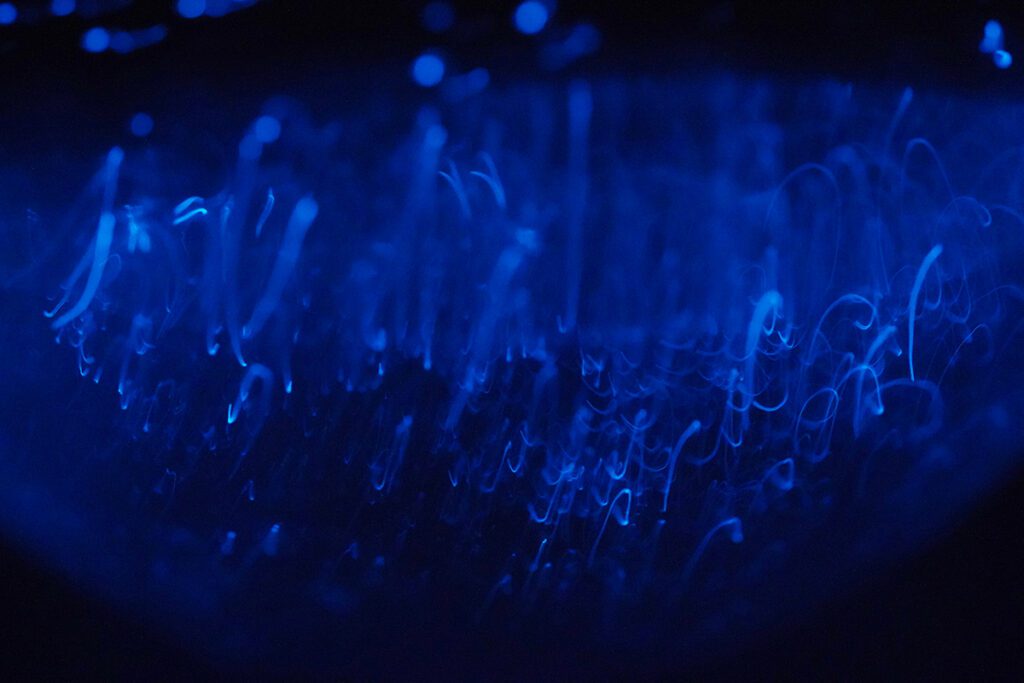

My initial photographic investigations with the glowing light were simple exposure charts to better understand the life and light cycles of the organisms. I needed to learn when the organisms would glow the brightest and how long it would take their light to produce a recording on the surface of photographic paper. I started this process by creating photograms of the organisms in petri dishes and Erlenmeyer flasks on black and white photographic papers. This allowed me to find the correct exposure times inherent to the organisms.

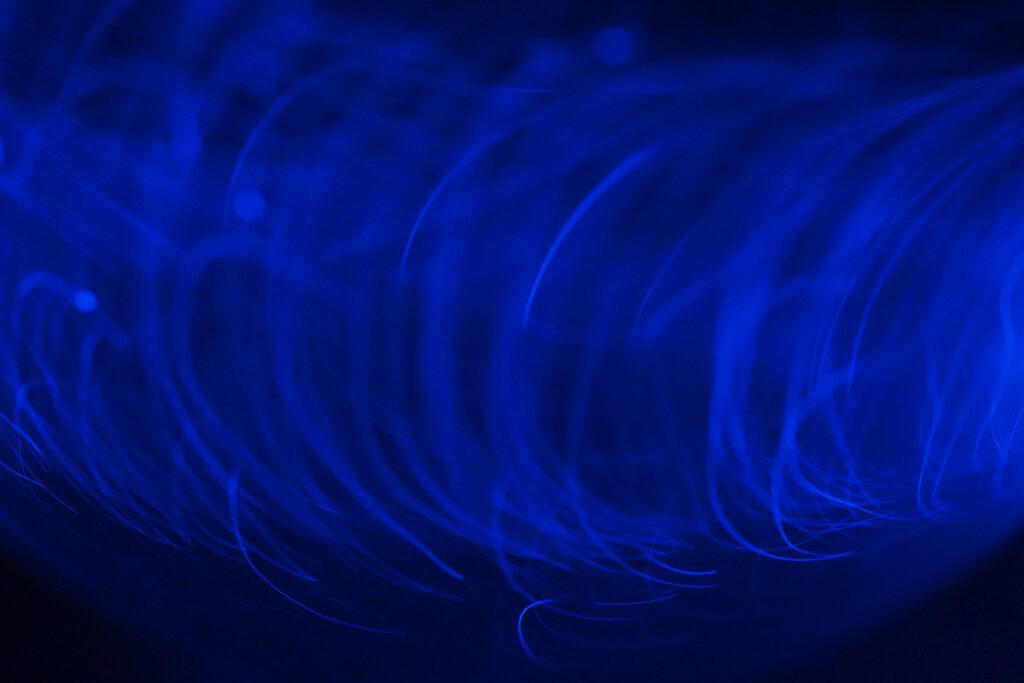

After I determined the technical parameters of working with each bioluminescent species, I transitioned to making images on large format color film. I continued the photogram process, documenting the natural growth patterns of the organisms and working with performance-like movements in the darkroom to create illusions of overlap and transparency in the two-dimensional photographic space.

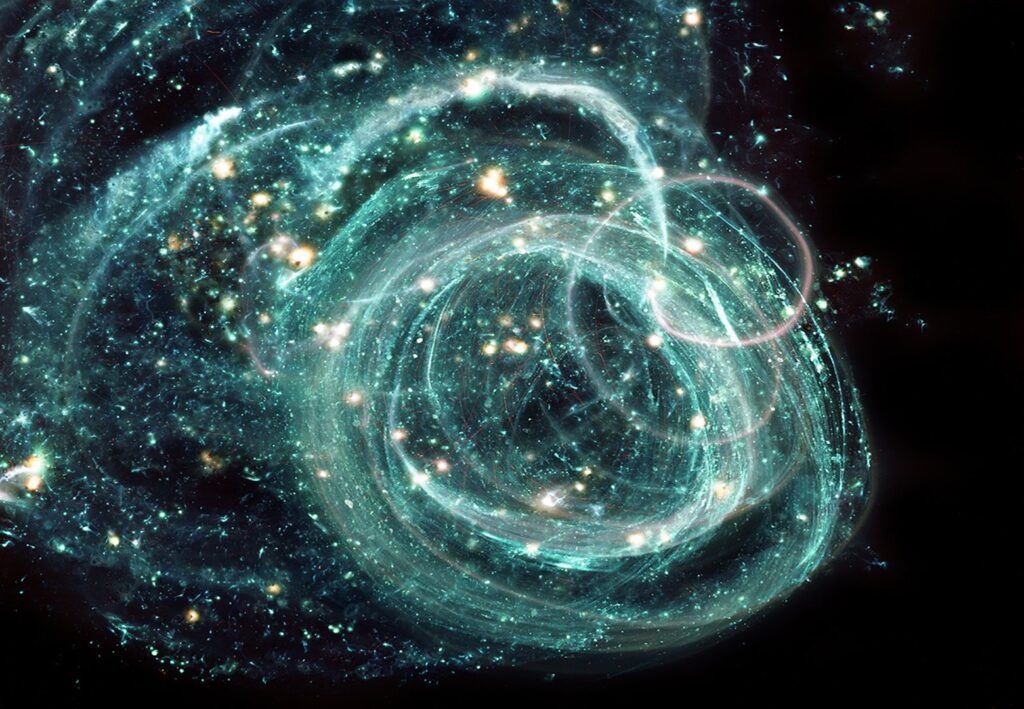

My work took on a more painterly quality when I began to work with ostracods, a Crustacea organism about the size of a sesame seed. From the same family as shrimp and crab, this tiny marine creature can deploy a burst of blue bioluminescence into the water to warn off predators and attract mates. Drawing on the surface of film with re-animated ostracods, I began to experiment with mark making and gesture in reference to the growing number and strength of hurricanes churning across the northern Atlantic. These works, which appear to be part celestial and part sea, render the bioluminescence as navigator beacons mimicking the night sky for our attention.

While I wasn’t able to find the bioluminescence in the Chesapeake Bay again, these glowing organisms helped me to discover compelling interconnections between terrestrial and marine systems. When powerful storms flood concentrated animal feeding operations, excessive nutrients are released into the watershed. When these waters, with elevated levels of nitrogen and phosphorus, hit warming ocean waters, harmful algal blooms can develop. These blooms, often called Red Tide, are created by an overgrowth of dinoflagellates.

These cross-species collaborations reflect a curiosity and wonder at the natural world. By harnessing the fleeting light of dinoflagellates, bacteria, and other glowing species, I connect to these tiny creatures, and work toward a non-human-centered world. Wonder is a survival skill, an imperative to help us find hope and innovation amidst the climate crisis. And blue bioluminescence may guide the way.

Photo by Margaret LeJeune

Photo by Margaret LeJeune

Margaret LeJeune is an image-maker, curator, and educator from Rochester, New York (USA). She received an MFA from Visual Studies Workshop. Working predominantly with photographic-based mediums, LeJeune explores our precarious relationship to the natural world. Her work has been widely exhibited at institutions including The Griffin Museum of Photography (USA), The Center for Fine Art Photography (USA), ARC Gallery (USA), Circe Gallery Cape Town (South Africa), Science Cabin (South Korea), and Umbrella Arts (USA). LeJeune has been invited to create work at several residency programs which foster collaboration between the arts and sciences including the Global Nomadic Art Project – The Ephemeral River (England), University of Notre Dame Research Center (USA), D’art et de Reves(Canada), and Hambidge Center for Creative Arts and Sciences (USA). She has been awarded a Puffin Fellowship, The Sally A. Williams Artist Grant, and a Bradley University Research Excellence ‘New Directions’ Grant for her interdisciplinary project Growing Light. Her works have recently been published in Evolving The Forest from art.earth press (UK) and Becoming-Feral from Objet-a Creative Studio (UK). LeJeune is an Associate Professor of Photography at Bradley University in Peoria, Illinois. She is currently serving as a Visiting Associate Professor in the School of Photographic Arts and Sciences at Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT).

To learn more about the work of Margaret LeJeune visit margaretlejeune.com / @margaret_lejeune