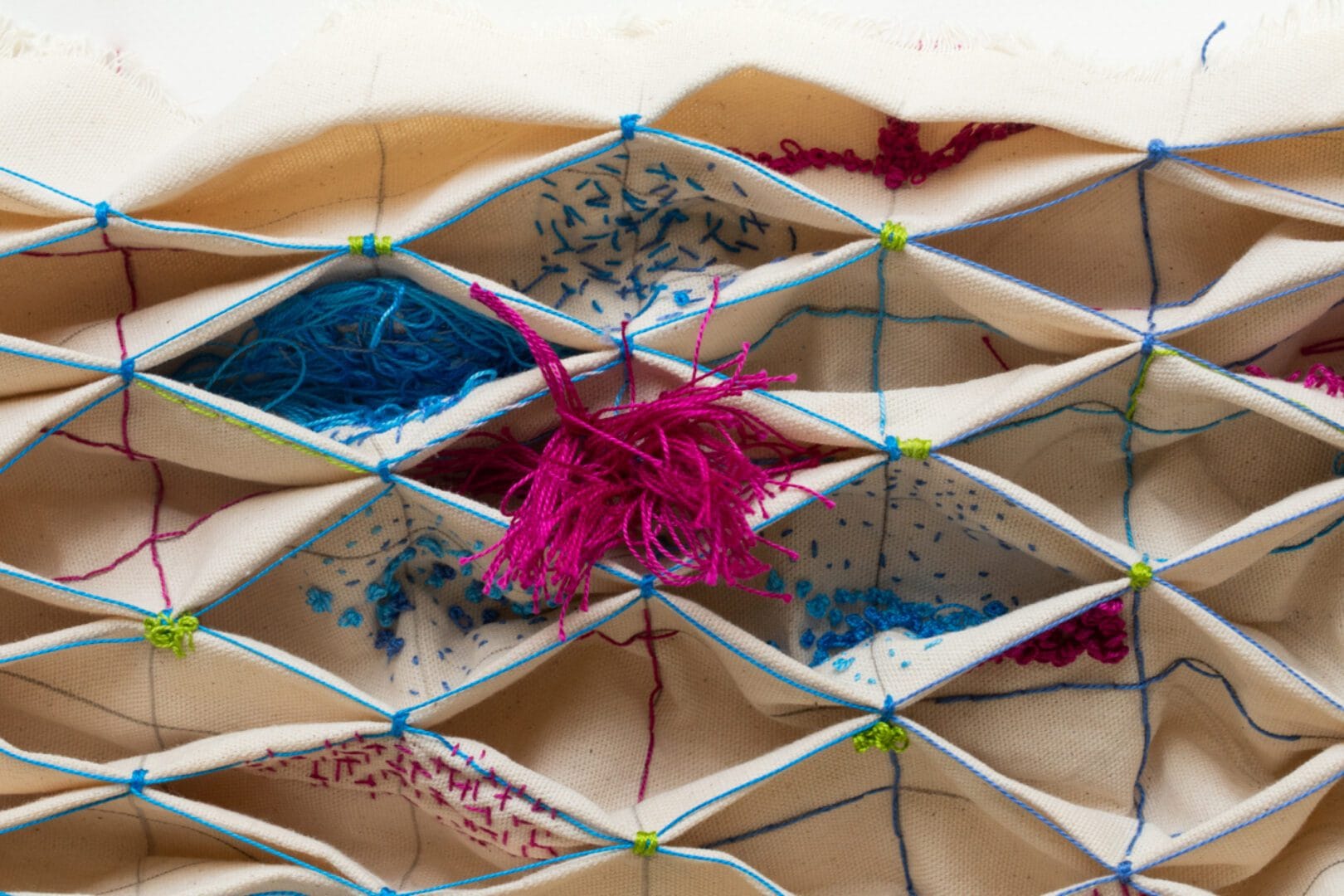

COGGAN SEES THE NEWLY FORMED, DIAMOND-SHAPED COMPARTMENTS BUILT BY THE WORK OF SMOCKING AS A SERIES OF INTERIOR ROOMS. EACH CAN BE AN INDEPENDENT WORLD, ISOLATED FROM THE OTHERS.

Annie Coggan, both architect and artist, has an intuitive grasp of what it means to transform two dimensions into three. She has been thinking through what she calls “the logic of smocking” for three years. In her classes at TATTER, Coggan makes the analogy between smocking fabric and constructing a building. “The integrity of a building and its ability to stand up and to shelter you depends on four structural components: the foundation, the framing, the cladding and the roofing.” Smocking, too, contains each of these elements. Like a building, smocking “begins with a grid,” she says, “the architectural foundation.” Coggan asks students to measure and then draw an actual grid onto cloth. The grid becomes armature when it is stitched to create regular pleating. This might be understood as the framing. The pleated columns are then whip-stitched together in a checkered interval pattern.

“This relates so utterly to architecture,” says Coggan.

Coggan sees the newly formed, diamond-shaped compartments built by the work of smocking as a series of interior rooms. Each can be an independent world, isolated from the others. She occupies these rooms one by one, embellishing every compartment uniquely. Her intricate work of serial embroidery unfolds only after the structure of the three-dimensional smocked fabric is achieved. “I have to respond to the room. There must be walls first. Then I can go about outfitting that room with stitching.” Perhaps only an architect with Coggan’s focus on interiors would commit to this sequence. She forfeits the ease, or the more acute finesse, that she might achieve if she were to work a flat fabric.

Though Coggan admits she spends time in each “room chamber” in her smocked pieces, she also zooms out, balancing the composition as a whole — building a suite of linked pockets. Each chamber of the whole must relate to every other.

Encountering one of Coggan’s smocked pieces, you see a tactile, sculptural work of art. Without knowing the history and structure of smocking, it would be easy to miss the depth of what lies beneath. Originating in England in the late 18th century, smocked garments were created for farmers. The persistence of smocking is grounded in its functional efficacy: how the technique affords shaping, padding and insulation. Pleating and connecting areas of the garment physically alters its shape, creating an elastic surface without sacrificing mass. The excess fabric becomes a kind of padding (good for resting a heavy farm tool) and the pleats themselves become an insulation — providing a ductwork of airflow, a natural, tubular system of heating and cooling.

Smocking fabric creates a honeycomb, gathered folds rising to ridges and giving way to cupped pools. Coggan’s honeycomb is especially resonant now. In quarantine, we inhabit independent micro-worlds, intermittently associated through the application of structure. We are a hundred autonomous human chambers linked by Zoom into collective experience, our rectangular individuality multiplied across screens. We are isolated, and yet connected. Together apart.

Learn more about the art and design work of Annie Coggan.