BLACK HAS MANY COMPLEX MEANINGS BUT IS OFTEN ASSOCIATED WITH THE EARTH, FERTILITY, DEATH, BEAUTIFUL AND SHINING BLACK SKIN, AND THE LIMITLESSNESS OF DEEP AND ESOTERIC KNOWLEDGE.

What is your relationship with the colors blue (black), red and white? What do these colors: (as hues, or as dyestuffs) represent in the West African cultures that you studied?

In traditional Yoruba chromatography, there are three primary colors White (Funfun), Black (Dudu), and Red ( Pupa). Indigo (Aro), specifically dark indigo, is often understood as a shade of Black. It is typically derived from the Elu plant (lonchocarpus cyanescens). In contrast, white was typically derived from Kaolin Chalk. A common source for red for dyes and cosmetics is Camwood powder (Osun), derived from the heartwood of baphia ntida, Pterocarpus souyaxii, or Pterocarpus osun. These pigments are used to paint shrines, religious objects as well as for initiations. White is a color symbolizing purity, light, and coolness. Orisha (deities), Such as Obatala (the lord of the white cloth) who shaped humanity, is associated with white regalia. Many deities associated with water, such as Osun, Yemoja (river goddesses), and Olokun (The sea god/goddess), are also associated with the color white. Black has many complex meanings but is often associated with the earth, fertility, death, beautiful and shining Black skin, and the limitlessness of deep and esoteric knowledge. Indigo and indigo dyeing are also associated with particular deities as well, Osun and Iya Mapo (a goddess associated with numerous feminine arts and industries) being two prominent examples. Red is associated with heat, aggression, and virility. Sango the Orisa of fire and thunder, his wife Oya the goddess of the whirlwind, are two very prominent examples. It is important to note that as Yoruba religious principles emphasize balance, these pigments may be used in sacrifices and rituals for each of these deities as they each have the potential to manifest each of these qualities.

Can you expand upon your experience with material and dye, and your interest in the use of Kola nuts, Camwood, and Indigo?

I was first exposed to Indigo and Kola Nut dyeing while studying at the Nike center for art and Culture in Ogidi Ijumu. I also learned how to dye yarns with a species of sorghum that yields a reddish-brown color. Although I knew about the use of Camwood for dyeing fibers from interviewing artisans and dyers in Nigeria, I did not begin to use it in my artistic practice until I returned to the U.S. My interest in using these dyes came from descriptions of a now-defunct cottage dyeing industry that was once an essential part of many Nigerian weaving traditions. Only indigo dyeing and, on occasion, Kola nut dyeing continues to survive into the modern-day. As an artist fascinated by pre-colonial Africa’s art and culture, thinking of how to incorporate these ancient techniques into my work was very important.

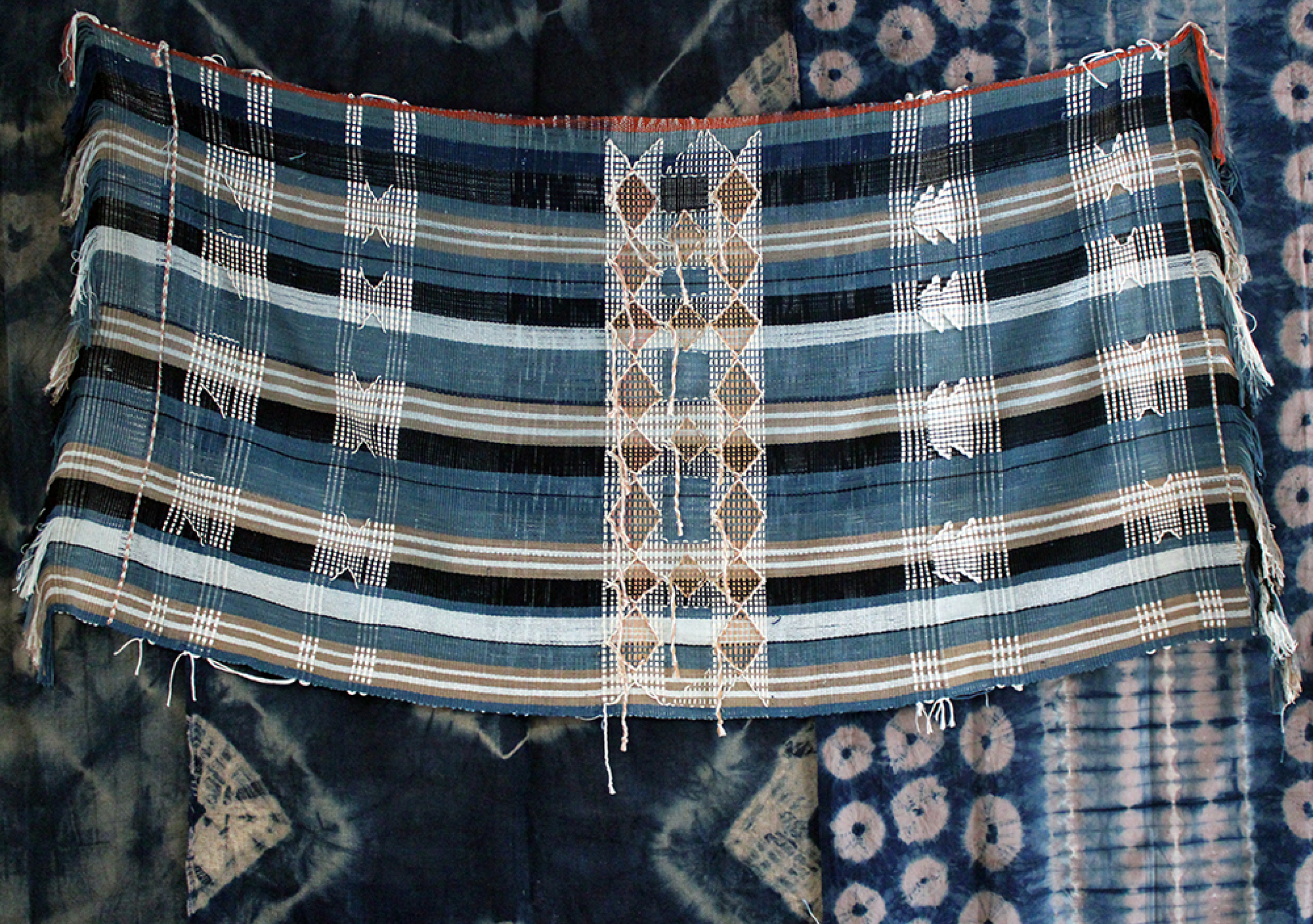

What Is the material used in your weaving?

Most of my work uses naturally dyed cotton. This is the primary fiber used to weave Kijipa, the sturdy handwoven cloth woven on the upright loom. I use both mercerized lace weight crochet yarn and unmercerized natural cotton twine of different weights. I also use silk as certain dyes have a better affinity for Silk and other protein fibers. For certain cloth, I will also incorporate Raffia, which accepts dye very well when pre-soaked long enough despite being hydrophobic. These three fibers were once ubiquitous in many Nigerian weaving traditions. Today machine-spun, synthetically dyed cotton and rayon predominate in most traditional weaving centers, while raffia weaving still predominates in certain weaving centers in the Southeast, such as Ikot Ekpene.

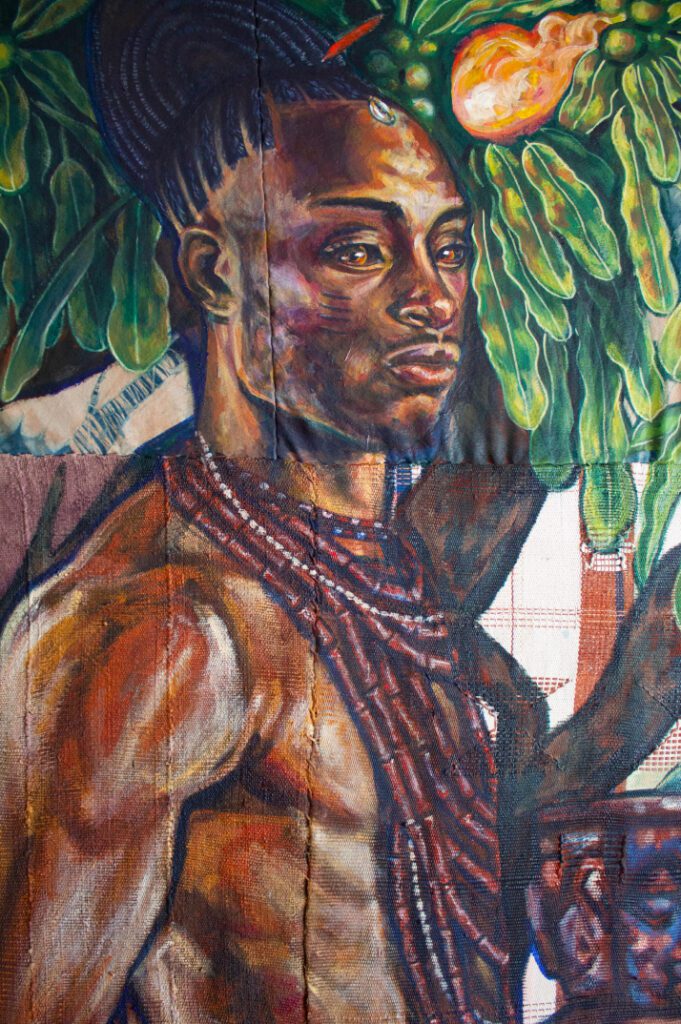

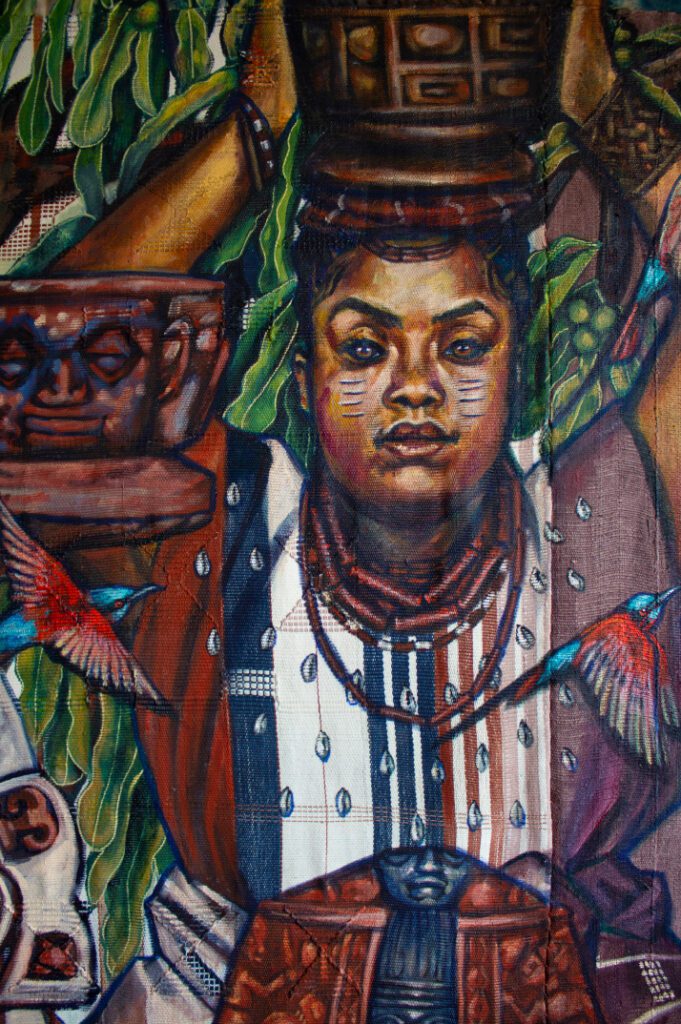

Can you elaborate on your choice to place figures on a woven ground? How does this ground act specifically as metaphor?

There are many aesthetic reasons why I enjoy painting figures on handwoven cloth. One of the most prominent is that it is a way to merge my background as a painter with my weaving and dyeing practice. The work blends the historical traditions of decorative display cloths used in many West and West-central African cultures with western portraiture and figurative painting. In this way, the cloth moves back and forth between the foreground and background, informing the pieces’ symbolism and composition in both dynamic and subtle ways.

LEARNING WEAVING AND DYEING, SURROUNDED BY COTTON PLANTS AND INDIGO BUSHES, IN WHAT ONCE WAS PART OF A CENTER FOR CLOTH PRODUCTION IN THE PRE-COLONIAL ERA HELPED ME APPRECIATE THE SYMBOLIC MEANING OF WHAT I WAS LEARNING. THROUGH WORKING WITH THESE MATERIALS, I RECLAIM THAT STOLEN LABOR AND RECONNECT WITH THIS ANCIENT KNOWLEDGE.

How did you arrive at the decision to place figures on top of the cloth background, as opposed to weaving the figures in?

As I said in the last response, my background before I started weaving was in figurative painting. I studied illustration in college, so I wanted to find a way to bring both art forms together in my work. Weaving the figures into the work would add more time to an already time-intensive process, in addition to not giving the desired effect.

Can you discuss which indigenous African techniques inform your work?

I incorporate traditional upright loom weaving (Aso-Ofi), woodcarving, and resist dyeing (Adire) into large scale, mixed-media installations. I also create clothing and other textiles, metal, and wood-based objects for photo and performance work.

What is the concept you refer to: ‘reclaiming ancestral wisdom?’ How did you come to be introduced to this concept, and can you describe your decision to pursue it?

My interest in learning about the African past began in childhood. It has informed my work for as long as I can remember. This desire to reconnect with this heritage led me to travel to Nigeria to study at the Nike center for art and culture. Having the opportunity to live in Nigeria and learn the history and folklore tied to cotton and indigo helped me reflect on my own experiences and history as an African American. The ancestral knowledge and traditions surrounding these materials in Nigeria and other parts of West Africa were exploited on plantations in the Americas for centuries.

Conversely, the connections between these industries and African systems of knowledge have been dissociated from us in the diaspora. Cotton and Indigo, crops associated with wealth, prestige, and even medicine, became associated with suffering and toil through the trauma of the transatlantic slave trade. Learning weaving and dyeing, surrounded by cotton plants and indigo bushes, in what once was part of a center for cloth production in the pre-colonial era helped me appreciate the symbolic meaning of what I was learning. Through working with these materials, I reclaim that stolen labor and reconnect with this ancient knowledge.

Do you have thoughts about your practice which includes more than one medium? What do you access in weaving that is different from painting – and vice-versa?

Weaving is a very meditative practice. It requires patience, focus, and finding a rhythm. It is a dedication to a slow additive process, one that cannot be rushed. Painting is a different experience. As I am a reasonably fast painter, the process isn’t as slow. I am also more of an intuitive painter, whereas weaving, though requiring incredible imagination, is a more systematic and rhythmic process for me.

Can you speak a bit about the weaving in your work- what does it give you? What and who do you connect to in doing it? How is that different from painting and drawing?

Because of the ancestral connection I have with the weaving tradition that I practice, there is almost a spiritual connection that I have to act. Although I will always have a love for painting and drawing, weaving means something different to me. This tradition’s role in the history of the African Diaspora impacts who I choose to teach it to and the community I am trying to build around these art forms in the United States. I consider weaving on this loom a Black artistic praxis, one that is my inheritance. Being gifted with this knowledge informs my identity in ways that differ from figurative drawing and painting.

To learn more about the work of Stephen Hamilton visit itanproject.com