Elizabeth “Sweetheart” Eaton Rosenthal is an artist and former textile designer whose home in Carroll Gardens is known for its singular color scheme and sprawling garden. Everything, from her counters to her kitchenware, is bright lime or kelly green. From her hair to her shoes–both of which she dyes green in her bathtub–Elizabeth walks the streets of New York with her bright green backpack and sweet and easy smile, stopping for selfies with strangers and bringing a pop of color everywhere she goes.

In 2008, she first appeared in the news as the “Green Lady of Brooklyn” for a feature in New York Magazine, featured alongside other monochrome New Yorkers in an article titled “One is the Loveliest Color.” In the years since, she has become a local celebrity, a folk hero of sorts. Neighbors and admirers leave green offerings, such as candles, housewares, or frogs on her doorstop. While she has only “been green” for the last 25 years, Elizabeth Sweetheart has been a beloved fixture in the New York art world and the Manhattan Garment District since the 1960s.

This past January, Elizabeth’s husband of 59 years, Robert Rosenthal, sent TATTER an email inquiring about our interest in a donation of vintage textiles. In a phone call with our Library Director, in which he detailed his large storage unit packed to the brim with vintage textiles and textile scraps, he casually mentioned that we “might know his wife, the Green Lady.” He had us piqued at vintage textiles, but now he really had our attention! Unbeknownst to us and likely many of her worldwide fans, Elizabeth once worked with designers like Calvin Klein and Ralph Lauren to create iconic designs that still appear on clothing today.

Over a cappuccino prepared in her little green coffee machine, we sat in the shade of her fig trees to learn more about her and her career in the textile industry. Born in Nova Scotia, Canada, in 1941, she learned how to paint and sew clothing from her grandmother, and got her “green thumb” from her father, an accomplished surgeon and gardener. She went on to receive a fine arts degree from Mount Allison University, where she studied with renowned Canadian painter Alex Colville. Unable to find work after graduation, Elizabeth began hitchhiking across Canada and the United States, eventually moving to New York City in 1964 with nothing but her pillow, ice skates and sketchbook. She recounted asking a kind stranger how to find a place to live and was told that she needed to find a job first, so that’s what she set out to do. An unemployment agency found her a job that day in the Garment District.

She took on various jobs in the Garment District, becoming known for her fine hand. Elizabeth’s delicate brush strokes and eye for color placed her in high demand, and she spent her first years in New York rushing around Manhattan from studio to studio with paintings and sketches rolled under her arm. She remembered working for a woman who “was difficult to work with” but “liked [her] little flowers.” Before the digital age, converters were artists who would either create a new image or take an existing design or motif and turn it into a repeat pattern that could be printed seamlessly on bolts of fabric in multiple colorways. She worked for many of the industry’s textile design converters and became incredibly skilled and experienced in the trade.

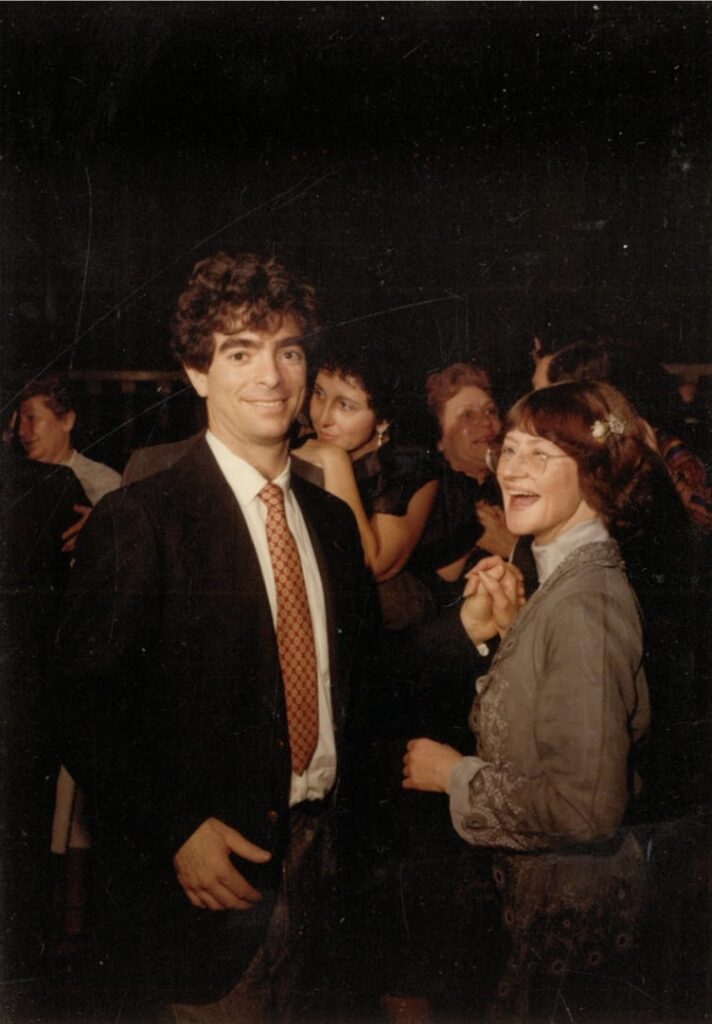

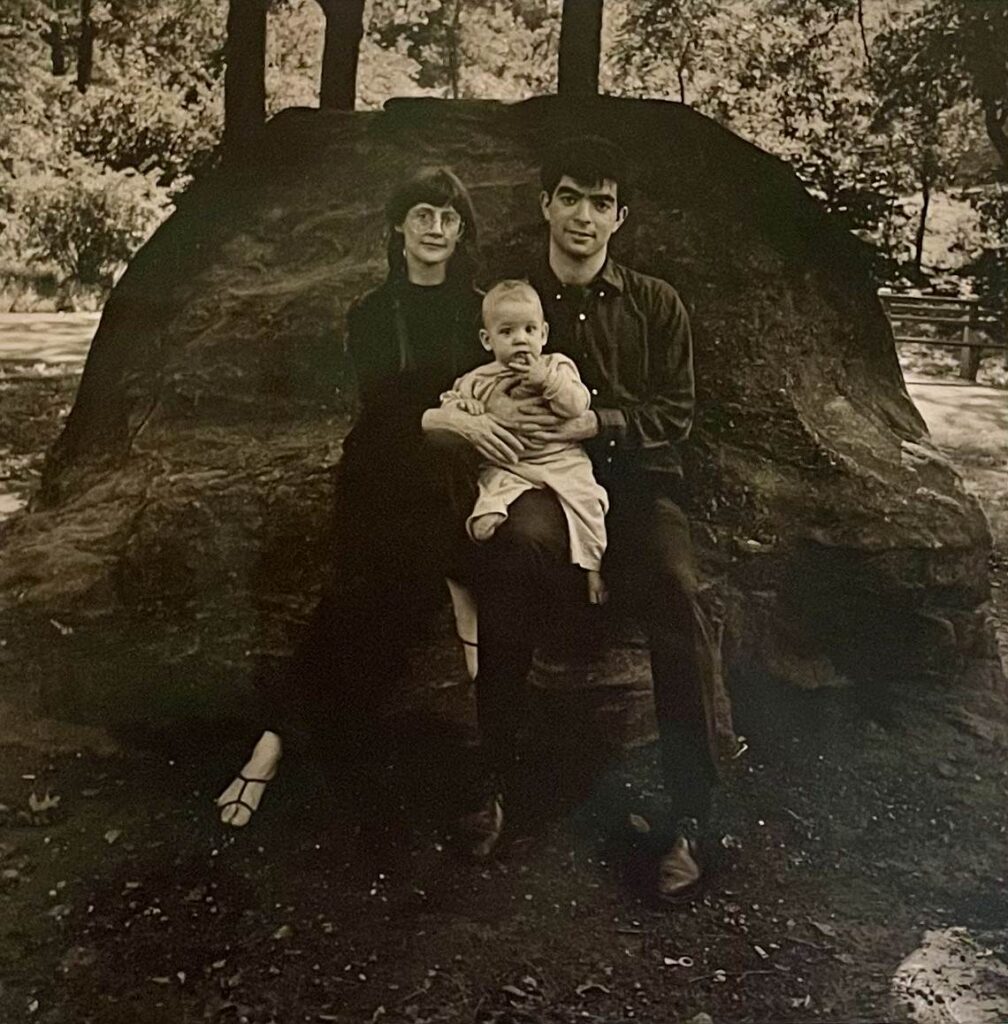

Robert and Elizabeth were both in their 20s when they met at the now iconic Ukrainian eatery, Veselka’s, in the East Village. The young beatnik couple married young and became parents shortly thereafter, making their way within the countercultural milieu of 1960s Manhattan. “You used to be able to go to a party where the youngest person was a teenager and the oldest was in their eighties,” Robert remembered, “there was just all this community.” They experimented with various forms of religious worship, becoming whirling dervishes for a few years, and when their son Sam was born in 1967, Elizabeth went right back to work, toting him around with her as she traveled between design studios. Once Sam was old enough to attend a daycare, they found a place near Chinatown where they could pick him up and take him to martial arts movies at the local Chinese theaters. There were often live performances before the film, and Sam began practicing magic tricks as a young child to perform for his mother’s friends and clients. “He was a born entertainer,” Elizabeth told me, “which is probably why he became a mentalist.”

By 1987, Elizabeth had been working as a converter for a studio in Manhattan when she finally hit her limit. Overworked and underpaid, she quit and went back to Nova Scotia for a few months. While there, she began plans for her own studio with friend and Korean artist, Yoon Li. That year she opened SweetPea Designs, named after the “amazing sweetpeas” in her father’s garden. She ran a bustling studio of artists for over 15 years, at one time employing a team of 17 people. When an untrustworthy bookkeeper was exposed for theft and tax fraud, she was forced to close the business. “Elizabeth never believes anyone is cheating her,” Robert told us, “she thinks everyone is a friend. So that’s where I came in.”

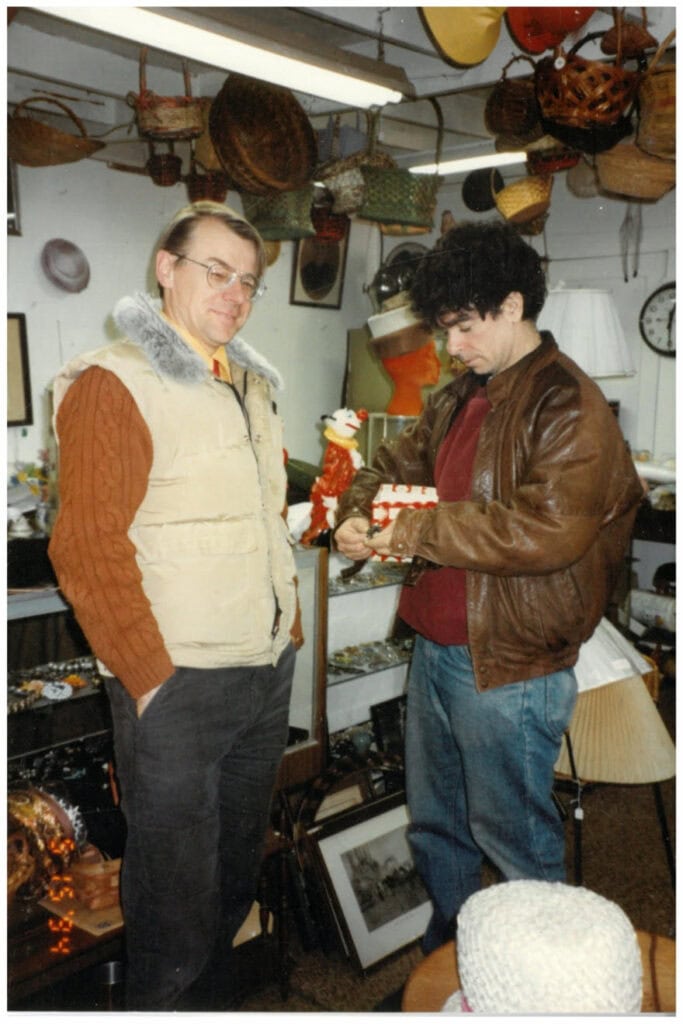

Together, Robert and Elizabeth opened Sweetheart Fabrics on 40th Street. An artist and self-described “history buff,” Robert had been working as a painting and plastering contractor for decades. His real joy had come from buying vintage and antique fabrics for SweetPea, reading up on textile history and becoming an expert in his own right. By the time they opened Sweatheart together, Robert was already known to local resellers and fabric collectors. As the buyer for the business, he began regularly scouring flea markets in the tri-state area and New England in search of patterned antique and vintage textiles. Robert fondly recounted the bygone days of enormous flea markets in Manhattan–”two or three on Canal Street, one over by the Museum of Natural History, a couple on the East Side.” He’d return from shopping trips with duffel bags stuffed with dizzying arrays of fabrics–1930s feedsacks, antique quilts and upholstery fabrics, retro novelty designs. He wasn’t looking for intact pieces, instead chasing even the tiniest scrap of historical textile designs. “Sometimes I’d know a pattern wouldn’t sell,” he told us sheepishly, showing us a few pieces of fabric he has kept in the house, “but I just loved it. I just knew I had to buy it.”

By the early 2000s, the rise of the digital age and the exodus of garment work from New York spelled a dramatic industry shift too all-encompassing to ignore. “You know how I knew it was over?” asked Robert. “We had a designer come up to us and say ‘I want an Art Deco pattern done in this year’s colors.’ Everyone wanted you to do it on the computer, and even though we tried to make the shift to digital, it just wasn’t how we worked.” Robert and Elizabeth shut down the business, closing the studio and putting their massive collection of textiles into storage. They’re now enjoying their retirement, happy to reminisce about their Garment District days and eager to see their fabric collection take on new life. Today, Elizabeth spends most of her time gardening, caring for their dog GeeGee, and steadily making their home greener and greener.

Whenever she is asked how and when she became the Green Lady, Elizabeth says that “it just happened.” As with most things in life, it happened gradually and mostly unintentionally. She has always loved color and played around with other colors in years prior, for a time donning lots of pink. Circa 2000, on a trip to visit her parents in Florida, she was inspired once again by the bright green of her father’s garden. She recounted going into a local beauty supply shop for a new polish, as she enjoyed painting her own nails. She wanted a green but they only had a dark, forest green. “I don’t like anything dark, so I mixed it with yellow, and that’s how it started.”

She discovered that this yellow-green, relatively uncommon in fashion, makes her feel happy. The exclusive pivot to green evolved organically from a whim, a slow-and-steady impulse to cultivate joy. She began seeking out and dyeing her own clothing and accessories her “happy green,” even coating her now iconic green glasses, a move initially prompted by a metal allergy. She began putting a green streak in her hair, the color slowly making its way from head to toe. “I don’t think Robert knew what was happening,” she laughed. Owning many pairs of overalls, she dyed them all green too; she now owns about 30 pairs of green overalls, her garment of choice.

Organizing one’s personal aesthetic around a single color, and in Elizabeth’s case a particular color shade, isn’t something commonly encountered out in the world. The totality of tonal saturation is arresting, enchanting, delightful. A visual treat that inspires ulterior dimensions of feeling. Visitors to BLUE: The TATTER Textile Library experience a comparable chromatic immersion. The library’s floor to ceiling shelves and floor are painted a calming, vibrant blue. While the library certainly doesn’t require our books to be blue, the textile objects on display are curated to elaborate on the theme, a visual way to engage with the non-neutral import of blue and indigo in the global history of textiles. Libraries are amazing in their own right, but a library of color is a rare marvel. While the color blue typically offers a sense of peace and calm, Elizabeth’s chartreuse green is playful, cheerful, electrifying. Welcoming her into the BLUE Library was a singular experience. She positively glowed, a luminous green spark in a more subdued sea. Her full-face smile is of course the true spark, her eyes twinkling under her green mascara and green rimmed glasses.

When we toured their storage unit earlier this year, we were blown away by the volume and diversity of fabric scraps in their care. Dozens of bins, bags, and boxes–displaying labels such as Florals, Novelties, Batiks, 19th Century Calico, Dots–held such a grand yet unassuming textile legacy. It was certainly more than we could bring into our archive, but we knew there was a thrilling potential here with these kindred spirits and their textiles. We decided to accession the portfolios of mounted fabrics that they used in their studio, adding Elizabeth and Robert to TATTER’s Legacy Collections. We were further blown away by their generous donation of the remainder of their collection for a scrap sale library benefit, to help fund the buildout of TATTER’s expanded and more accessible home at 230 Ashland Place in downtown Brooklyn’s Cultural District.

So much of the textile work and fashion design that was once the beating heart of New York City has disappeared in the decades since Robert and Elizabeth opened their studio on 40th street. Many of the smaller cultural touchstones of the garment industry continue to close their doors for good. Our impetus as a textile library and archive in New York is to preserve and uplift that history and the hand skills many consider obsolete. On June 19th-22nd, 2025, TATTER will be holding its inaugural Scraptacular library benefit. The bulk of beautiful scraps on offer are the fabric samples and vintage clothing from the collection of the Green Lady of Brooklyn: historical fabrics, antique quilt blocks, and beautiful folk textile remnants from around the world. Additionally, off-cuts of original designer fabrics have been donated by Chinar Farouqui of Injiri, Susan Hahn of Auntie Oti, and Matthew Aprile of Indi & Ash. On the evening of Thursday, June 19th, we will be holding our ticketed preview event honoring Elizabeth, featuring a silent auction showcasing scrappy, original artworks from renowned textile artists in our community. We’d love for you to get scrappy with us and hope to see you there!