Margarita, 82, still remembers her mother’s Llicla. It had shapes of snails and flowers, she tells us. She wove her first lliclla together with her mother. These garments are incredibly slow to form. The weaving can take from two to four months, depending on how much time is spent on the loom each day. The women artisans in the region of Patacancha, Peru work daily tending their farms, grazing their animals, and caring for their children. These everyday activities are represented in their Lliclas.

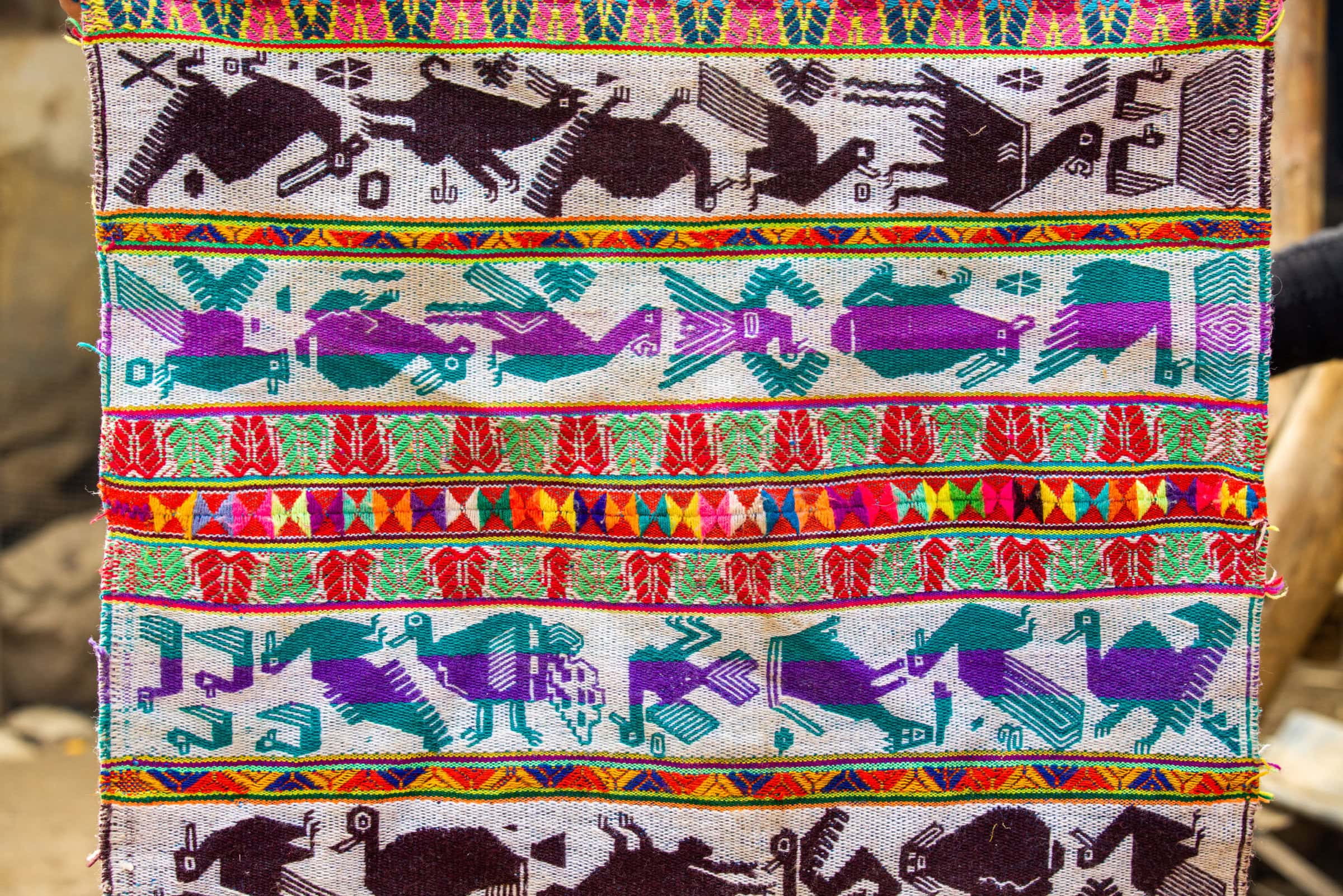

From land to loom is how these weavings actually come alive. Motifs of flowers, animals native to the region, such as birds, butterflies, llamas, and sheep, are woven throughout in the design ecosystem of their mantas. I feel protected when I wear it, it keeps me warm. Margarita shares. Lliclas are made of sheep’s wool. The ones owned by Margarita are naturally dyed, from native plant matter. Tones which softly reflect the landscape are growing steadily more scarce. Younger generations show preference for brighter, almost fluorescent colors, that can only be achieved with synthetic dyes.

Llicla is the Quechuan word for Manta, the Spanish word describing a woven cloth traditionally worn over a woman’s shoulder, covering her back. They are worn as protective coverings, sheltering skin from the elements. They are also used to carry harvested foods and dye plants, firewood, and babies.

FROM LAND TO LOOM IS HOW THESE WEAVINGS ACTUALLY COME ALIVE. MOTIFS OF FLOWERS, ANIMALS NATIVE TO THE REGION, SUCH AS BIRDS, BUTTERFLIES, LLAMAS, AND SHEEP, ARE WOVEN THROUGHOUT IN THE DESIGN ECOSYSTEM OF THEIR MANTAS.

Each Llicla is different, because they are woven with different hands, states Margarita. The beauty of this cloth is that it is personal. Even though the motifs are part of a collective ancestral vocabulary, you will never find two Lliclas alike. The colors and designs share a common typography, but the story is unique to the weaver.

Lliclas incorporate designs of natural elements because these mantas are thought to protect the wearer from disease. This specific kind of manta is not used for ritual. Another kind, with a squared shape, is used for those purposes. Yolanda likes her llicla. She tells us it is part of her cultural identity. “We don’t all think the same. Each llicla is different and we weave depending on what we like”.

EACH LLICLA IS DIFFERENT, BECAUSE THEY ARE WOVEN WITH DIFFERENT HANDS, STATES MARGARITA. THE BEAUTY OF THIS CLOTH IS THAT IT IS PERSONAL. EVEN THOUGH THE MOTIFS ARE PART OF A COLLECTIVE ANCESTRAL VOCABULARY, YOU WILL NEVER FIND TWO LLICLAS ALIKE.

Yolanda tells us about her mother’s llicla, she remembers it being large, and the time her mother gifted Yolanda her first llicla, she told her: Here you have your llicla, to carry your own. Yolanda wove her first lliclla at 10 years old. For her wedding Yolanda wove two lliclas: One, to decorate the table, that required four months to weave. Another one to wear, which required two months to weave. Yolanda weaves a new llicla for her daughter every new year of school. We also weave Lliclas when we are single. I have owned 20 lliclas in my lifetime, Yolanda shares with us.

Her daughter Yessica is now 15. The colors she enjoys are different as well. Lots of green, purple and light blues. The older generations show oranges, pinks and reds. I started weaving my llicla a month ago. I do it differently than my mother. My friends too, have different designs and preferences.

Awamaki creates lasting impact in the remote mountains of Peru by helping rural Andean women’s associations launch successful small businesses creating authentic, high-quality products and experiences. Awamaki invests in women’s skills, connects them to market access and supports their leadership so they can increase their income and transform their communities.

Awamaki is comprised of a Peruvian asociación civil and a U.S. 501(c)(3) non-profit organization working closely together to empower women’s associations, connect them to markets and enable them to lead their communities out of poverty. Though a non-profit, Awamaki uses market strategies to accomplish its charitable goals of increasing women’s income and business leadership.

For more information visit www.awamaki.org