Natural indigo has complex undertones and an unmistakable aroma that synthetic blues do not. As many blues as indigo can be, it is clear what indigo is not.

Earlier this year, author Jamaica Kincaid, art historian Cheryl Finley, and visual artist Rosana Paulino participated in a talk on art museums and the legacy of the Dutch slave trade. I “zoomed in” for their presentations and the conversation that came after. But the most striking moment, to me, was a brief exchange off to the side. A moderator made what they might’ve believed to be a passing comment, suggesting that cotton was a conspirator in European slavery. Kincaid paused to deliberately revisit it. Botany – cotton, sugarcane, spices – did not conspire, the Europeans did.

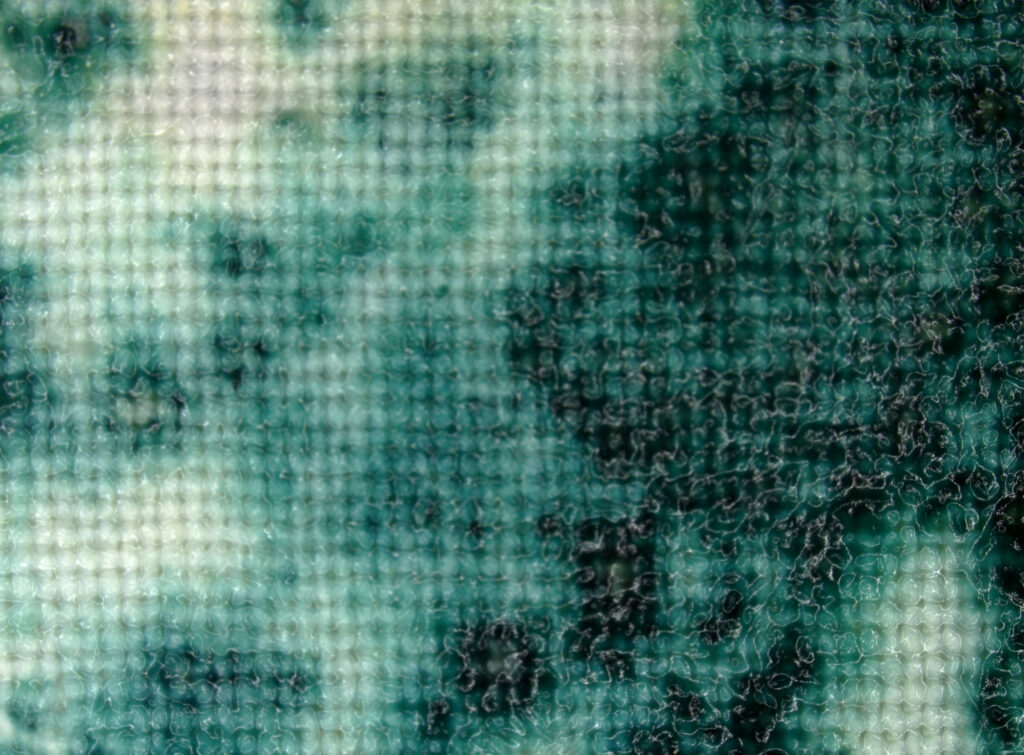

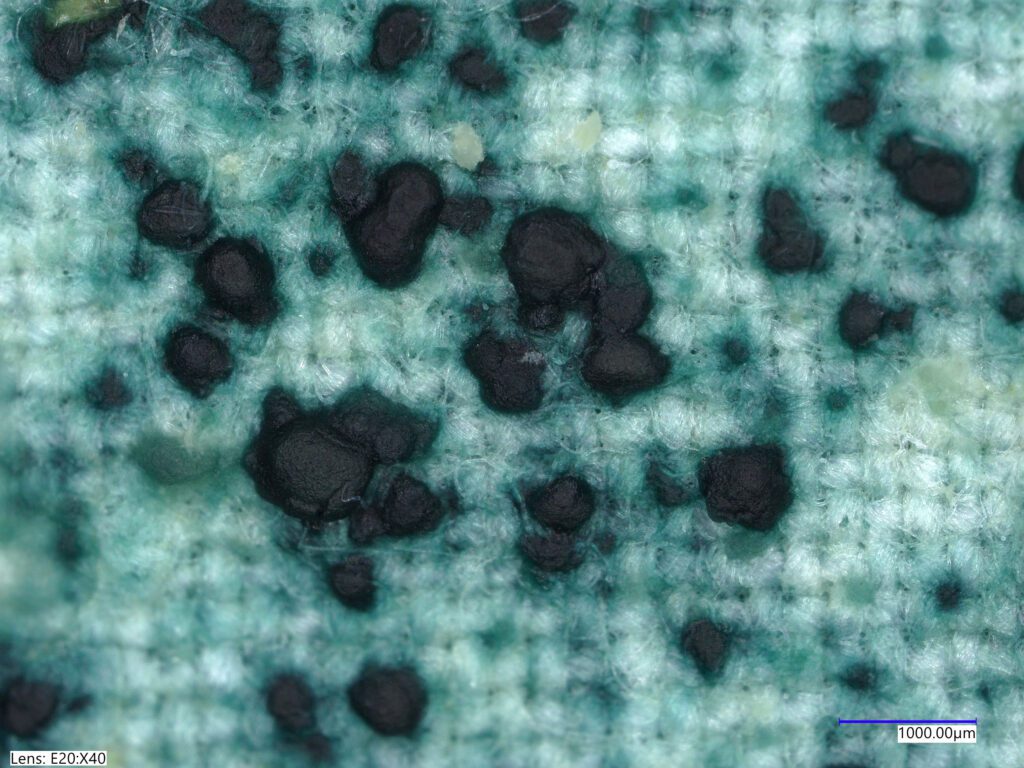

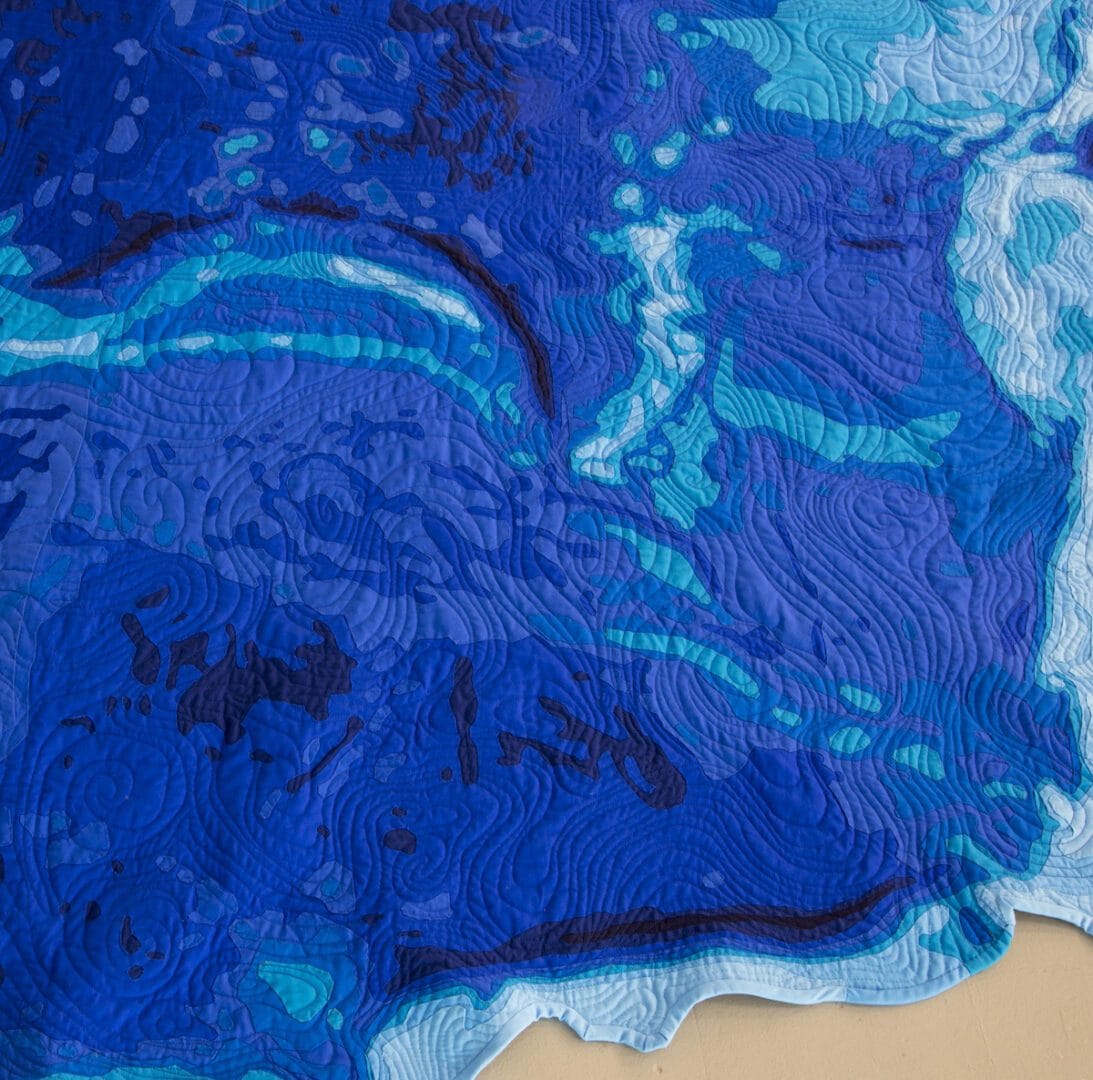

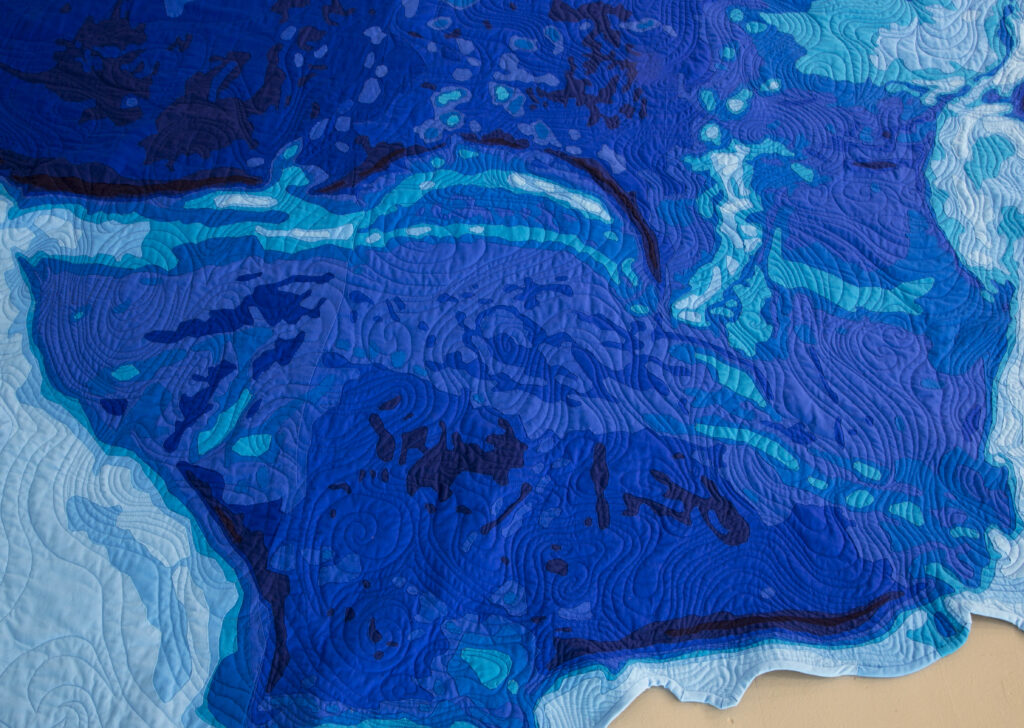

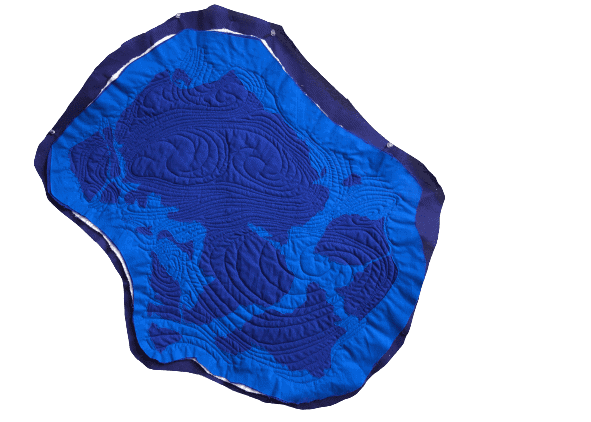

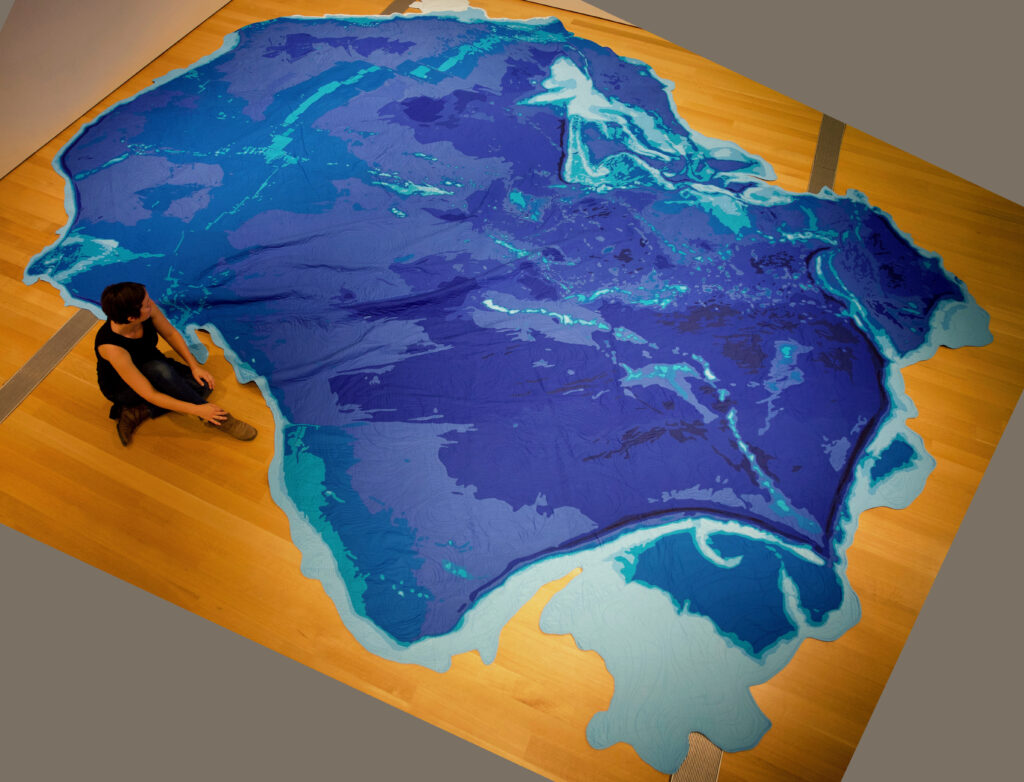

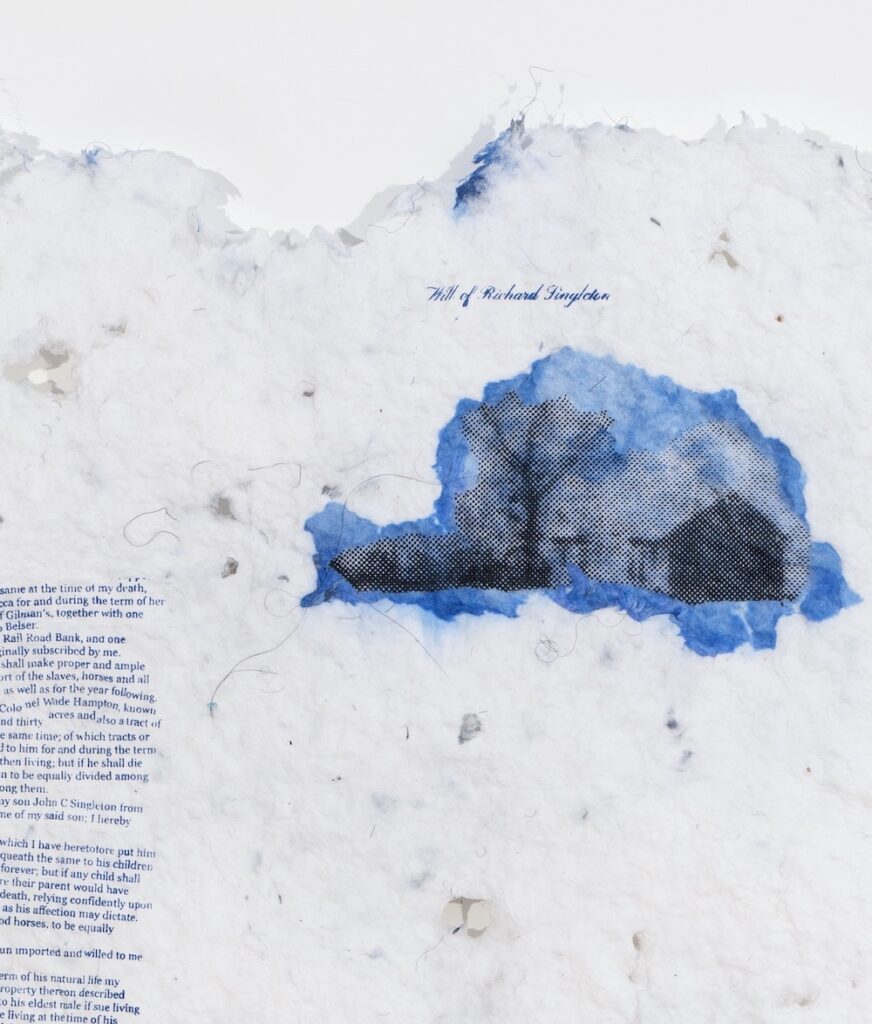

A few months later, I was in Harlem, on the second floor of a gallery operating out of a slender walk-up. I was there to see works from the True Blue series by Adebunmi Gbadebo. The gallerist, Ian, directed me upstairs to four framed artworks. They were resting on the hardwood floor, three leaned against the wall, and one against the back of a chair. I had shown up without notice. But still, Ian took his time, carefully peeling away the bubble wrap on one work that was ready to go somewhere else. True Blue refers to at least two plantations in South Carolina: the True Blue Plantation on Pawleys Island, which is currently a golf course, and the True Blue Plantation deeper inland in Fort Motte, where Gbadebo can trace her mother’s side of the family, the Ravenells. They were both rice and indigo plantations, where enslaved people cultivated indigo plants and processed those plants into blue dye. Archival documents identify 185 people of African descent enslaved on Pawleys Island – Mildred, Dolly, Little Anthony – but not much else about them. Gbadebo responded by creating abstracted portraits – ways to reconstruct their likeness using materials that can be connected to them: cotton, indigo dye, human hair donated by Black people. Blue appears in these works as a source of color, a knowledge held by skilled workers, a part of the region’s history.

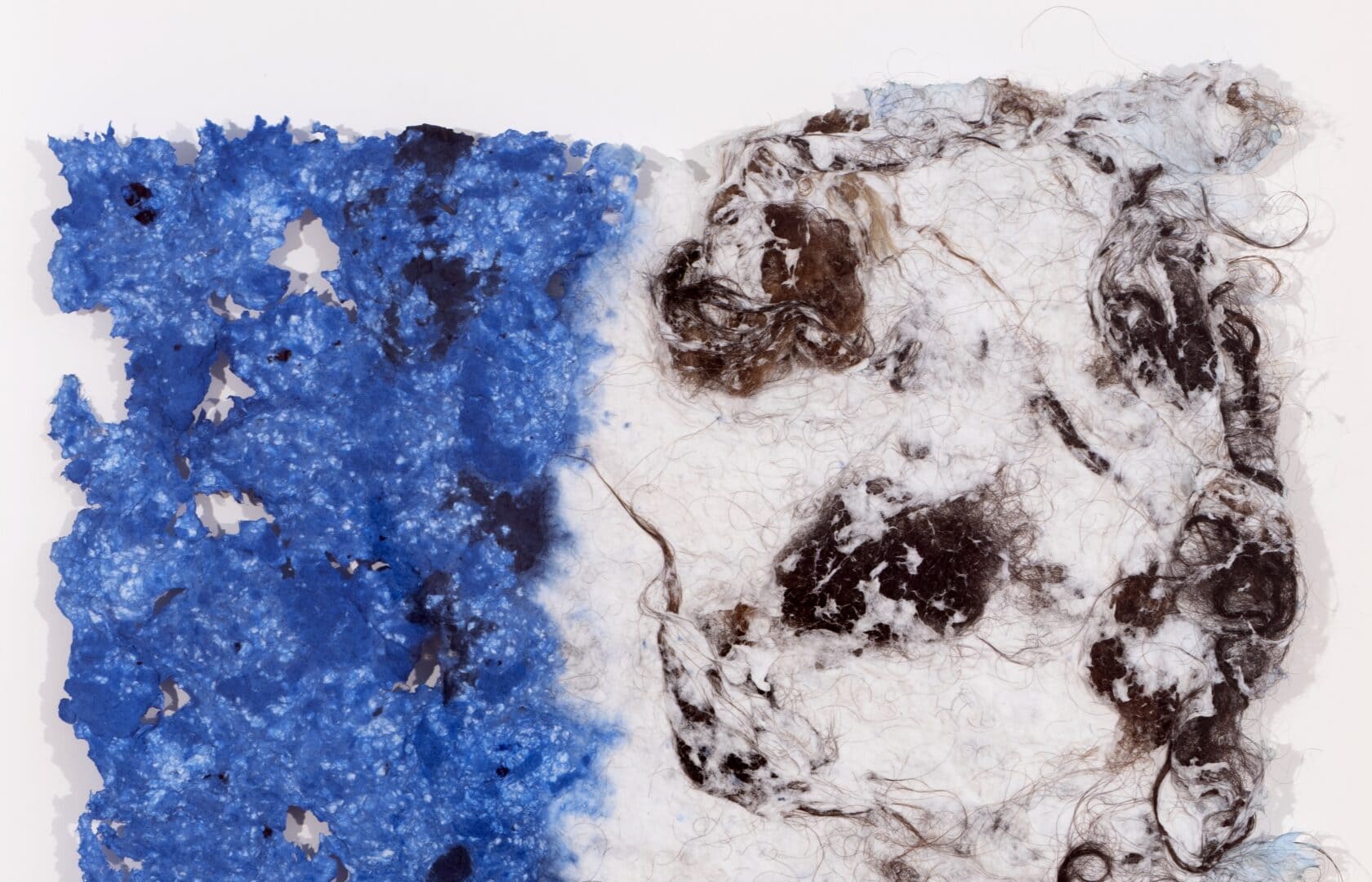

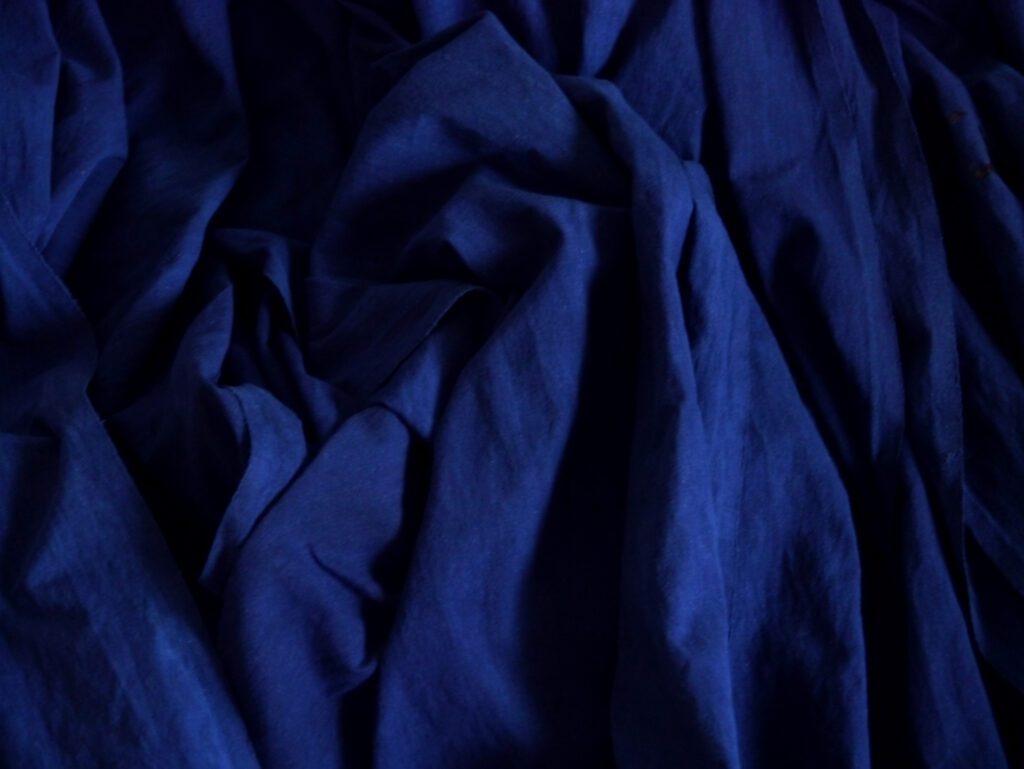

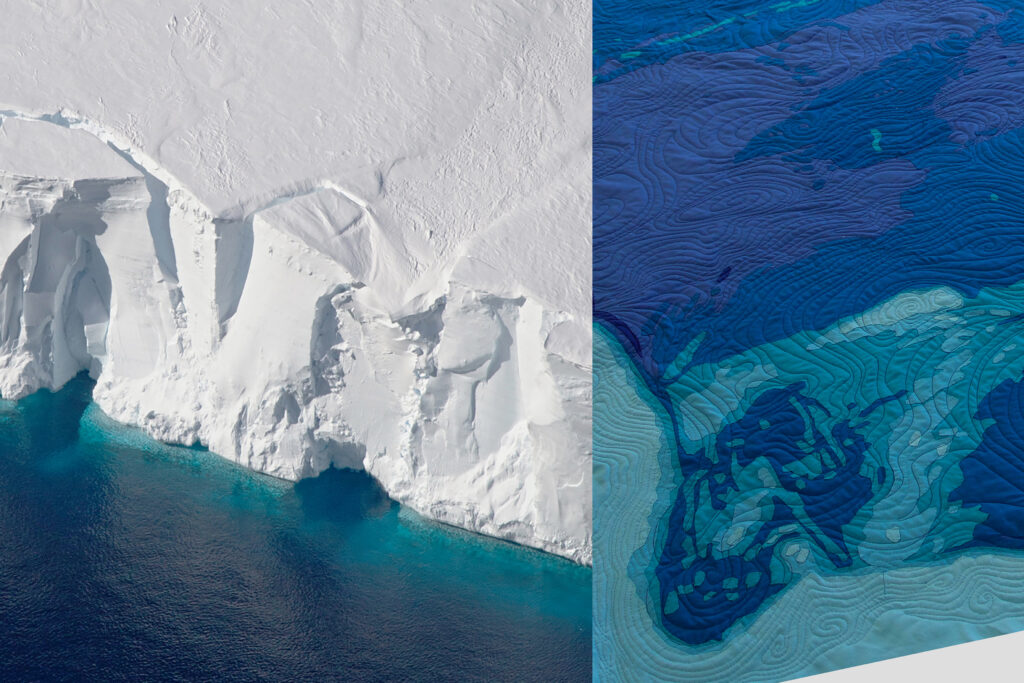

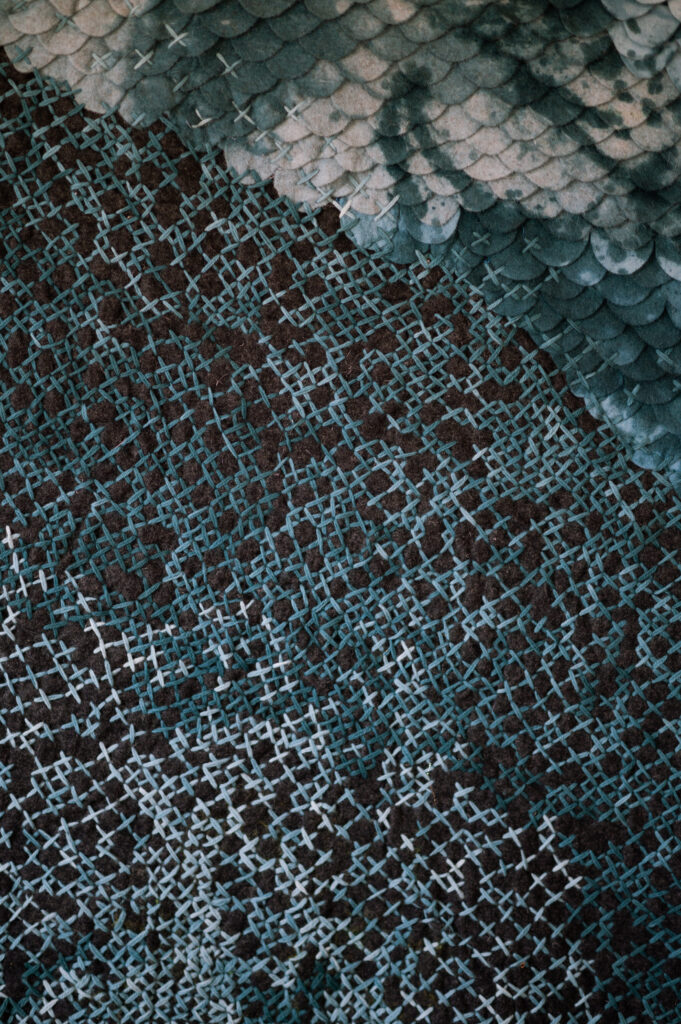

One work – the one on the wall all the way to the left, and the first one my eyes settled on – had hardly any blue. Frozen in a sheet of cotton paper were mounds of kinky-curly and curly human hair in a color that I can best describe as 1B (if you know, you know). The two works on the wall just to the right had several blues. A block of mottled electric blue divided one artwork into two. And with its alternating bands of deep blue-black and white, the other artwork reminded me of tie & dye. At the boundary between the bands, the blue bled briefly, so it was never really white. I wondered which blues came from indigo and which from later, synthetic dyes. Because it’s a vat dye, where color is layered on in multiple dips, a knowledgeable dyer can make indigo’s blues anything from an icy blue to a night sky. But I was sure that electric blue wasn’t from indigo. Natural indigo has complex undertones and an unmistakable aroma that synthetic blues do not. As many blues as indigo can be, it is clear what indigo is not.

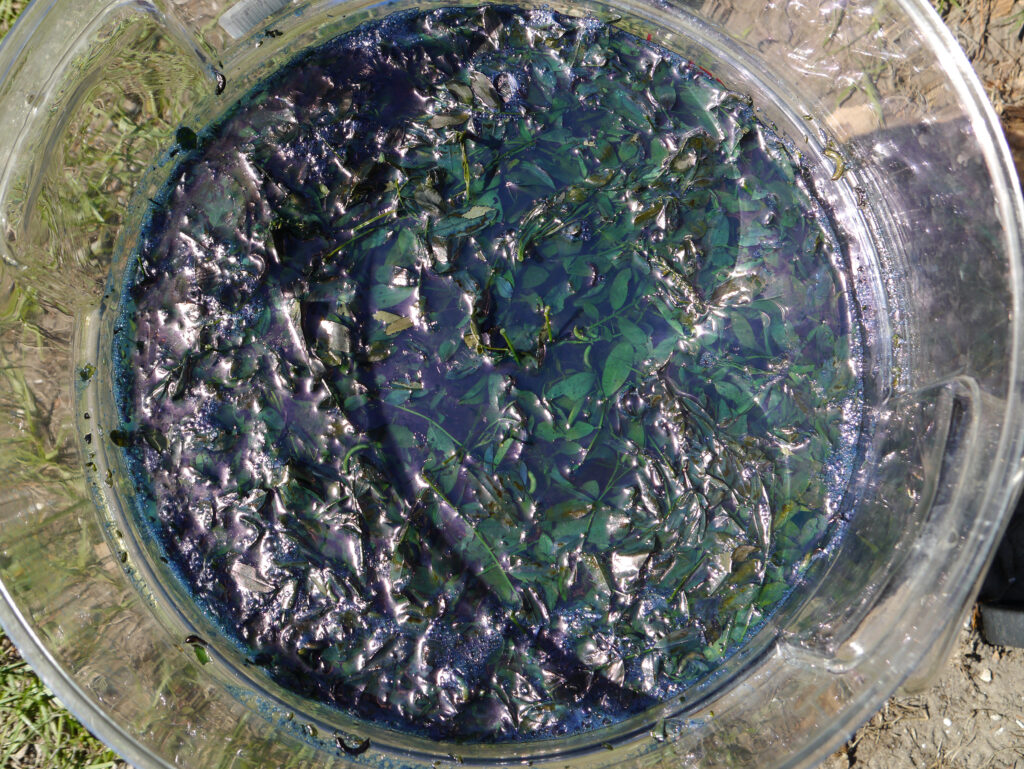

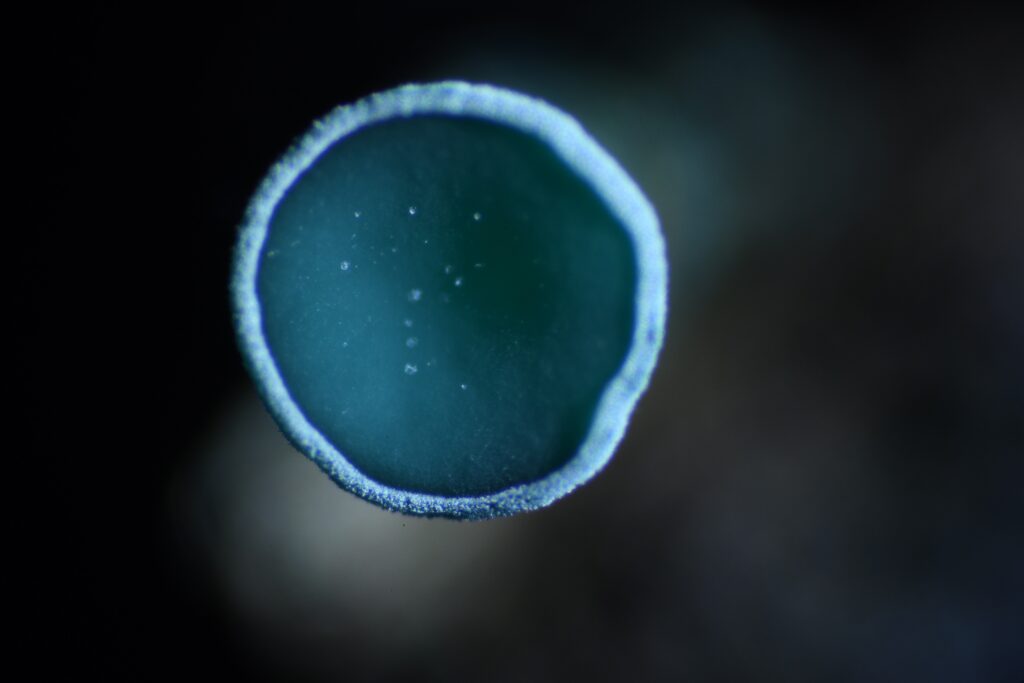

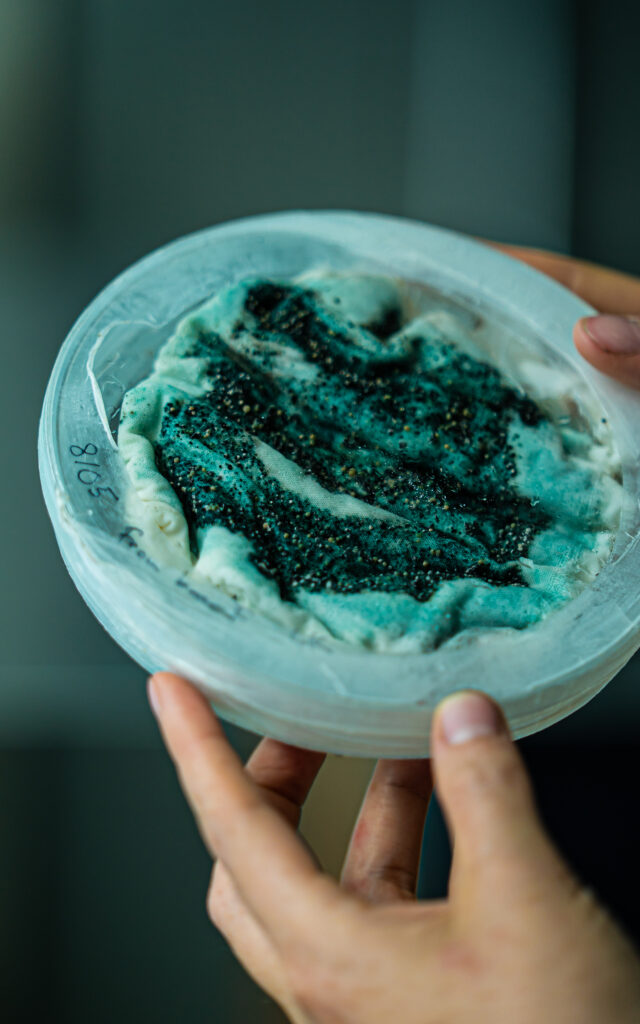

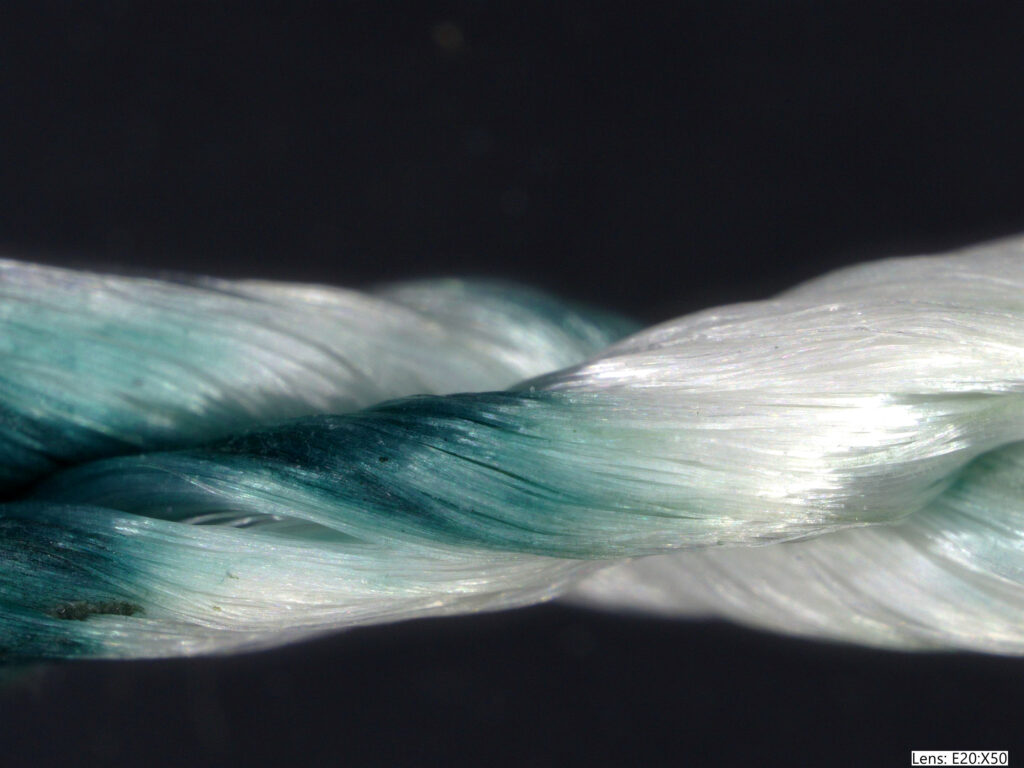

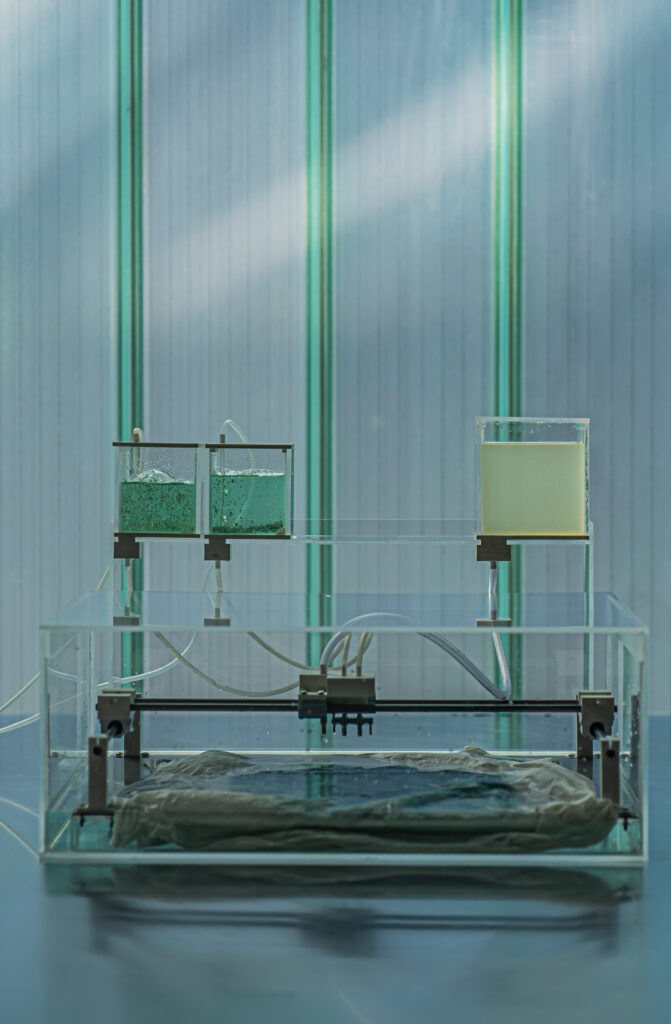

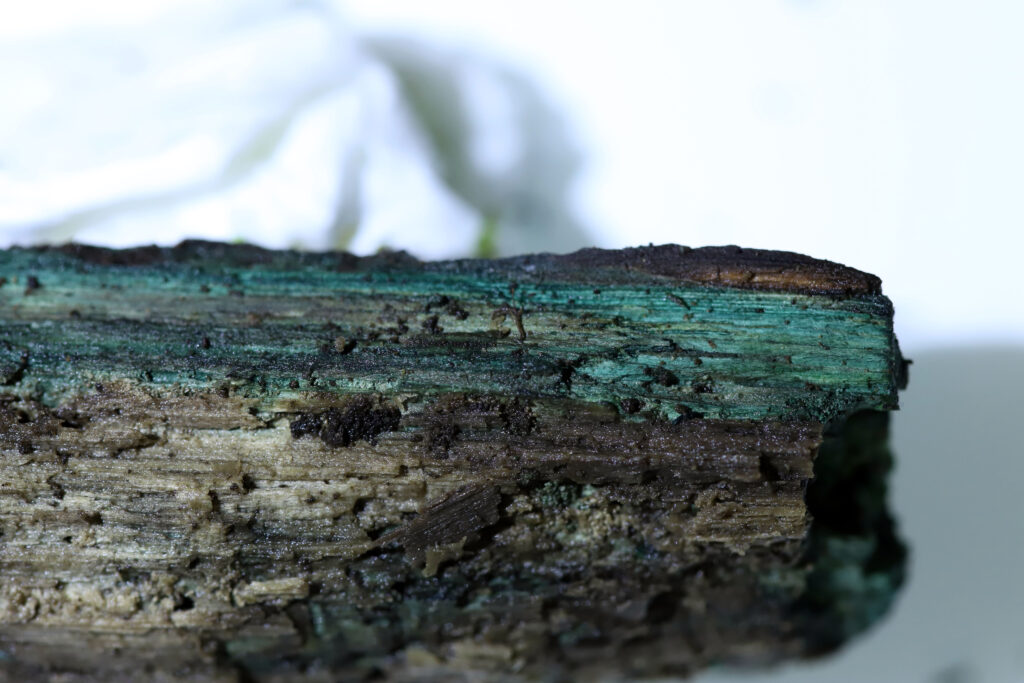

Gbadebo and I spoke in a video call the day after my visit. We spoke about kinks and curls being an artistic medium of their own. Short naps swept up from the barbershop floor are just right for paper-making. The resolute spirals and z-shaped kinks of 4b and 4c hair are just right for sculpting. And the looser, slack curls – well, she’s still learning that language. Gbadebo showed me a video of a recent trip to Forte Motte, only possible with the guidance of her cousin, Jackie Whitmore, one of several family members still living there. The video was thick with the colors of the place. There was the green brush in the family cemetery, springing up almost past their heads; and the burnt-orange silt under their feet. The cemetery is a sanctuary – land the Ravenell family inherits, hallowed ground where enslaved ancestors were buried, a place of safety in Fort Motte. Jackie stewards this land, devotedly. And of course, we spoke about blue. The color palette has indigo blues, like I’d thought, but also synthetic blue hair dyes with names that held Gbadebo’s attention: “Royal Blue,” “Blue Black,” and even “True Blue.” We talked about how indigo connects her not only to her mother’s lineage in South Carolina, but also to her father’s lineage in Nigeria, where there are proud histories of indigo-dyeing from Kano all the way south to Abeokuta. We talked about the things she is still learning – connections between indigo dyeing practices in the American South and in West Africa, what the indigo production process looked like on colonial plantations, whether to work with different forms of indigo. She’s been creating vats from indigo dried and ground into powder, dipping the cotton pulp into the vat before forming it into paper.

We spoke for almost two hours, but I was struck by something that happened early in our interview. Gbadebo noticed that the silk scarf wrapped around my head, with its tail trailing from my nape down to the crest of my back, was an indigo blue. She loves the color, still, she marveled. Through the artworks in the True Blue series, Gbadebo calls out the devastating colonial and imperialist history surrounding indigo in her family; in two South Carolina plantations; and in European, then American, slavery. Is there still room for her to love indigo’s blues? Well, the way I see it, Gbadebo sees indigo and its beautiful blues just as Kincaid described. At times, an instrument, but never an accomplice.

To hear more about the True Blue series, directly from Gbadebo, check out the True Blue short film produced by the Jon Andre company and filmed by Scott Seldon. If you’d like to experience these works in person, they’re in these public collections (though check with the institution about when it’ll be on view):

- I Sang the Blues Black at Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (grid of 9) & National Museum of African Art (grid of 9) in Washington, DC

- True Blue 18th Hole (grid of 21) at the Newark Museum of Art, in Newark, NJ

- True Blues (grid of 18) at the Minneapolis Institute of Art in Minneapolis, MN

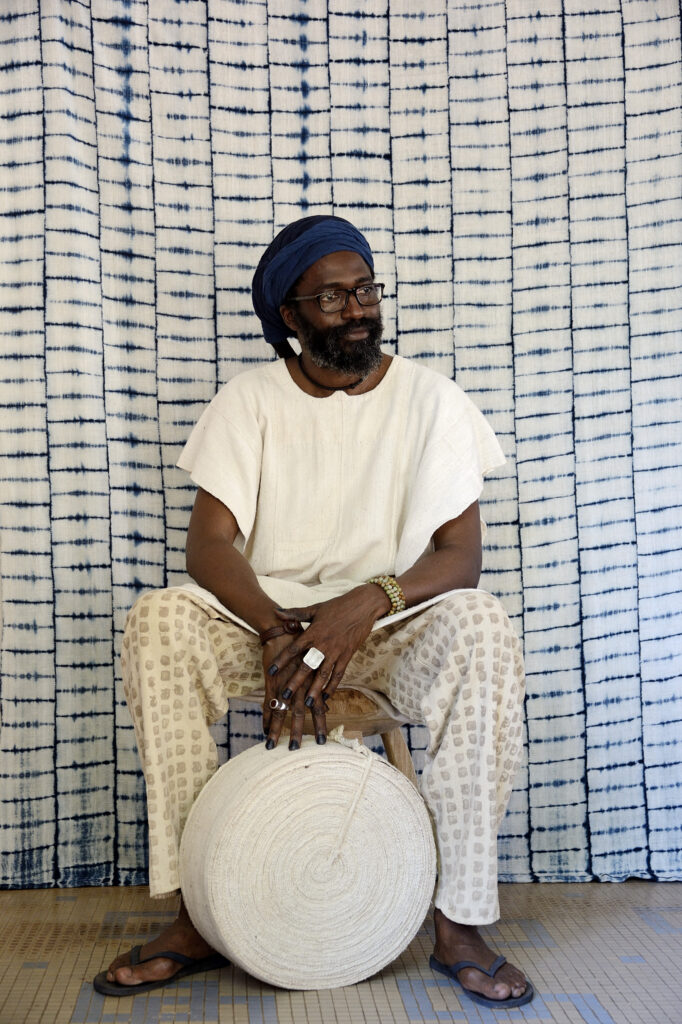

For more on that talk, where Kincaid, Paulino, and Finley address the legacies of American and European slavery through literature, artwork, and scholarship, the video is published online via the event sponsor, Harvard Art Museums. The 300+ year history of indigo in connection to American slavery is one part of a bigger picture, at least thousands of years old, of indigo plant species, uses, and techniques across the globe. For more indigo histories from various regions and times, refer to the lifelong work of indigo dyeing masters, educators and preservers, such as Aboubakar Fofana (who contributed a piece to this Blue issue), Chief Mrs Nike Okundaye / Nike Art Centre, Takayuki Ishii / Awonoyoh, Botanical Colors, and Threads of Life Bali. This list is not comprehensive; just a few suggestions based on my own learning experience. Lastly, thank you for taking the time to read this piece. If you have feedback, please email it to the Tatter staff, who will communicate it with me.

Interviews and research conducted November – December 2021.

Written by mary adeogun, with thanks to Helen Polson, the Claire Oliver Gallery, and Tatter editorial staff.

Adebunmi creates sculptures, prints, ceramics, and paper using historical and cultural imbued materials. Currently focused on her “True Blue and Land for Sale” series, Adebunmi investigates the complexities around land, erasure, and value in the American south. Born in New Jersey and based between Newark and Philadelphia, Adebunmi earned her BFA at the School of Visual Arts, NY.

Gbadebo’s work is included in the permanent collection at the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the Minnesota Museum of American Art, and the Newark Museum of Art. Gbadebo’s work has been presented in numerous exhibitions in the United States, Asia, and Europe, including the Dhaka Art Summit, Bangladesh; 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair, London; Untitled Art Fair, Miami; Rutgers University, New Jersey; College of Saint Elizabeth, New Jersey; amongst others. Adebunmi is a current resident at the Clay Studio. Philadelphia and represented by Claire Oliver Gallery in New York.

To learn more about the work of Adebunmi Gbadebo visit adebunmi.carbonmade.com / @adebooms