Following the Qur’an Muslims pray five times a day: at dawn, at noon, in the afternoon, evening, and night. During prayer, worshippers stand barefoot, bow, sit, and place their foreheads on a clean surface on the ground. While these prayers can be performed in the privacy of one’s home, worshippers also gather in mosques, especially on Fridays, and follow a leader (imam) performing the same ritual before them. Small floor coverings such as mats and carpets serve as a portable, clean place for ritual prayers at any location.

While praying, believers turn their faces in the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca, the most sacred place for Muslims. In a mosque, the direction of Mecca is usually marked as a niche, called a mihrab, and most prayer rugs incorporate this element as an arch shape within their design. While most prayer carpets are for one person, some large carpets, especially modern machine-made ones, repeat the same arched design, allowing rows of people to pray in individual spaces, in a mosque.

In our present days, COVID-19 has forced us to become familiar with isolation, cleanliness, and purification. Prior to praying, Muslims wash themselves with water, giving attention to hands, forearms, feet, face, mouth, ears, nose, and partially the head. As ablution cleanses the body, the prayer carpet prepares the mind of the believer–and even those around them–for the prayer. The carpet creates a defined space for worship.

As a young child I tried to avoid walking around my grandmother’s prayer mat when she was praying. For her, the arch on the mat probably offered a door to the spiritual realm. I was careful, always, not to pass between her and the direction of Mecca towards which she faced. Isolated on her mat, she could not be disturbed by anyone.

As kids, we would often be told to bring the prayer mat. Little did I know that I was carrying a magic door in my hands. Today as a curator, I see prayer carpets simultaneously as religious and artistic objects. The Brooklyn Museum houses several in its collection, rich in design and technique, and diverse in material.While the earliest surviving prayer carpets are more than 500 years old, most of them date between the 18th-20th centuries. Prayer mats made of palm leaves or woven textiles made of reed, cotton, or linen might have served the first Muslims living in hot regions. The use of wool carpets evolved along with traditions of the cooler climes in Central Asia and Northern Iran. Throughout history, several Muslim courts, from Spain to India, produced large-sized carpets that relied on expensive materials, including silk, reaching an extraordinary 500 knots per square inch. Nomadic tribes and villages, on the other hand, produced smaller unique carpets made of wool, often woven by women who drew upon both tradition and personal motifs. Persian and Turkish rugs are the foremost known examples. The arch of a niche is a primary motif of prayer rugs, but designers and weavers enriched this basic element with a variety of floral, geometric, calligraphic, and architectural embellishments. Human forms never appear, as their likeness is forbidden in Islamic religious contexts. Often, a lamp appears at the center of the arch, symbolizing God’s light. In the Qur’an, God’s light is compared to a niche with a lamp.

Here I share a few examples of prayer rugs from the Brooklyn Museum Collection.

An exquisite Persian prayer carpet from 17th century Iran was made by Qutb bin Kirmani, from the Iranian city of Kirman. His design resembles an illuminated page from a manuscript, with numerous calligraphic bands and cartouches layered over floral patterns (Fig.1). Unusually, he put his name in one of the outermost cartouches on the left. The remainder of the writings includes poetic verses (ghazal) from the famous 14th-century Persian poet Hafiz and other Shiite religious expressions. Such a complex design was most likely produced by the Safavid court wealthy enough to employ specialized labor and materials.

This rare 18th-century Turkish carpet comes from Gördes, a prolific carpet center in Turkey. In addition to its startling colors, a small carnation and tulip group, perhaps imitating a glass lamp, hangs down from the horseshoe-shaped mihrab arch (Fig.2). In its large cream-colored border, we see repeating floral arrangements featuring natural flowers beloved in Ottoman art of the 16th century.

This 19th century rug from Kula also comes from Turkey. As in the previous example, it retains the arch shape of the mihrab niche in its design but adds an architectural quality using two columns on both sides of the arch (Fig.3). When we look carefully, we see that the narrow rectangular area, reserved for putting one’s forehead above the arch, is outlined with a series of small pitchers, a visual reminder of the ablutions that precede the prayer. Below the two columns we also see larger, more defined pitchers strangely placed upside down. The top of the column above their acanthus leaf capital incorporates another peculiar motif, a small domed building next to several circles. Could these tiny renderings of buildings be a visual cue for the Turkish bathhouses that were used by the public for the ultimate cleaning of the body? Or perhaps they denote the tiny birdhouses that were specifically built as a shelter for birds on the facades of Ottoman mosques? Whatever they look like to us, the carpet’s maker and buyer would have recognized them.

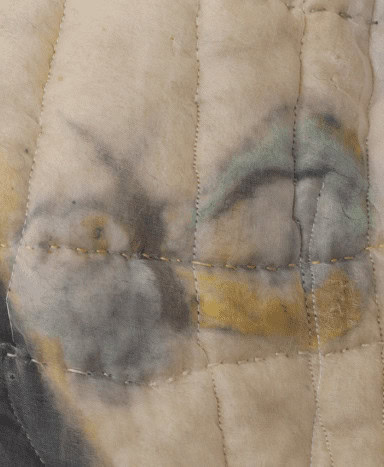

In this 19th century tribal rug from Shirvan, Azerbaijan (Fig.4) the arch in the design no longer plays a dominant role. Instead, numerous schematic motifs (trees) take up the main field. We also notice a comb motif under the arch. It is thought that it refers to the combing of the beard as part of the ablutions for the male worshippers before prayers. Why did the women who made these carpets incorporate such gendered motifs from their pattern stock? Perhaps they had male buyers in mind?

Prayer carpets are well worth a careful look to appreciate their design, colors, unique details, and overall beauty. With prayer being such a regular and essential ritual throughout the day, it is easy to imagine designers and weavers throughout history being inspired to articulate them with such beauty. As companion to worship, this textile performs quite a serious task. Though it may be portable, it effectively manifests a spiritual architecture, defining a time of day, a place in space, and a path to prayer.

Learn more about the collection of the Brooklyn Museum.